Indigenous Governance Database

blood quantum

A Legal History of Blood Quantum in Federal Indian Law to 1935

The paper traces the development of the use of blood quantum, or fractional amounts of Indian blood to define Indian in federal law up to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The paper shows that blood quantum was not widely used in federal law until the twentieth century, as the branches of the…

An Anishinaabe Tribalography: Investigating and Interweaving Conceptions of Identity During the 1910s on the White Earth Reservation

This article explores the varied ways in which the Anishinaabeg of White Earth defined themselves during the early twentieth century. It consists of two primary parts. In part 1 I go beyond the artifacts in order to enliven the history, to offer an alternative way of remembering the past. In…

Special White Earth Constitutional Reform Issue

As the White Earth Nation prepares for a referendum election to approve or reject the proposed constitution, the Reform Committee has implemented a series of citizen engagement activities that includes a special issue of the tribal newspaper to inform citizens of the election date, proposed changes…

Race and American Indian Tribal Nationhood

This article bridges the gap between the perception and reality of American Indian tribal nation citizenship. The United States and federal Indian law encouraged, and in many instances mandated, Indian nations to adopt race-based tribal citizenship criteria. Even in the rare circumstance where an…

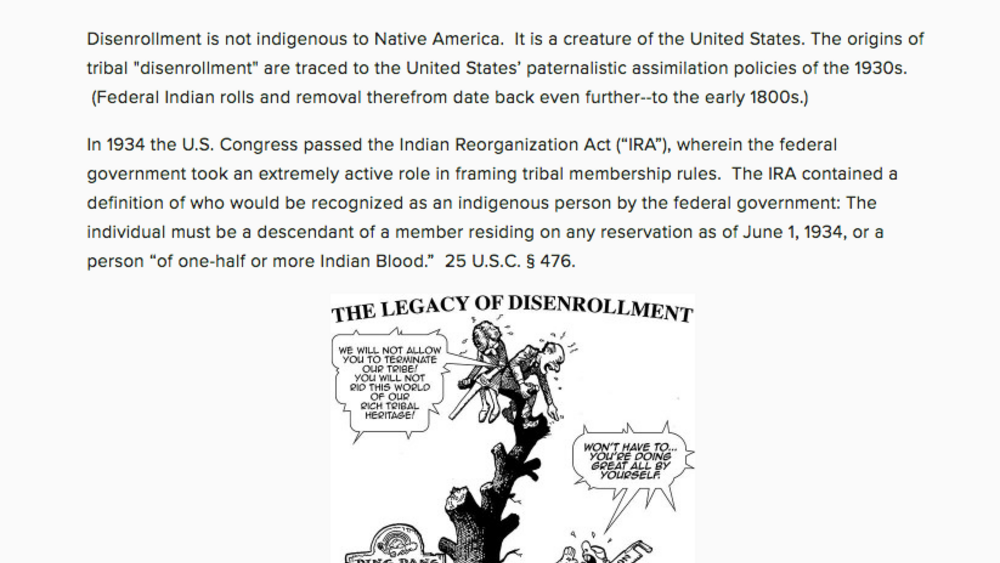

An Essay on the Federal Origins of Disenrollment

Disenrollment is not indigenous to Native America. It is a creature of the United States. The origins of disenrollment are traced to the United States’ paternalistic assimilation policies of the 1930s. In 1934 the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (“IRA”), wherein the federal…

Understanding the history of tribal enrollment

It's difficult to talk about tribal enrollment without talking about Indian identity. The two issues have become snarled in the twentieth century as the United States government has inserted itself more and more into the internal affairs of Indian nations. Ask who is Indian, and you will get…

The Will of the People: Citizenship in the Osage Nation

This teaching case tells the story of Tony, one of nine Osage government reform commissioners placed in charge of determining the "will of the people" in reforming the government of the Osage Nation. Because of Congressional law the Osage Nation had been forced into an alien form of government for…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …