Indigenous Governance Database

citizenship criteria

Westbank First Nation Circle of Governance

The people of the Westbank First Nation share the history and process taken toward self-governance and how it has transformed their community.

Nisga'a First Nation Circle of Governance

People of the Nisga'a Nation discuss custom and tradition before the Indian Act. They tell how they made the move back to traditional ways through strategic planning and abandoned oppressive ways of the Indian Act.

Redefining Tigua Citizenship

The materials in this informational guide are designed to provide you with important background information ”such as Tigua history, tribal population profiles, and fiscal impacts” related to upcoming membership criteria changes. Project Tiwahu is an Ysleta del Sur Pueblo-wide initiative to reclaim…

Special White Earth Constitutional Reform Issue

As the White Earth Nation prepares for a referendum election to approve or reject the proposed constitution, the Reform Committee has implemented a series of citizen engagement activities that includes a special issue of the tribal newspaper to inform citizens of the election date, proposed changes…

Race and American Indian Tribal Nationhood

This article bridges the gap between the perception and reality of American Indian tribal nation citizenship. The United States and federal Indian law encouraged, and in many instances mandated, Indian nations to adopt race-based tribal citizenship criteria. Even in the rare circumstance where an…

Understanding the history of tribal enrollment

It's difficult to talk about tribal enrollment without talking about Indian identity. The two issues have become snarled in the twentieth century as the United States government has inserted itself more and more into the internal affairs of Indian nations. Ask who is Indian, and you will get…

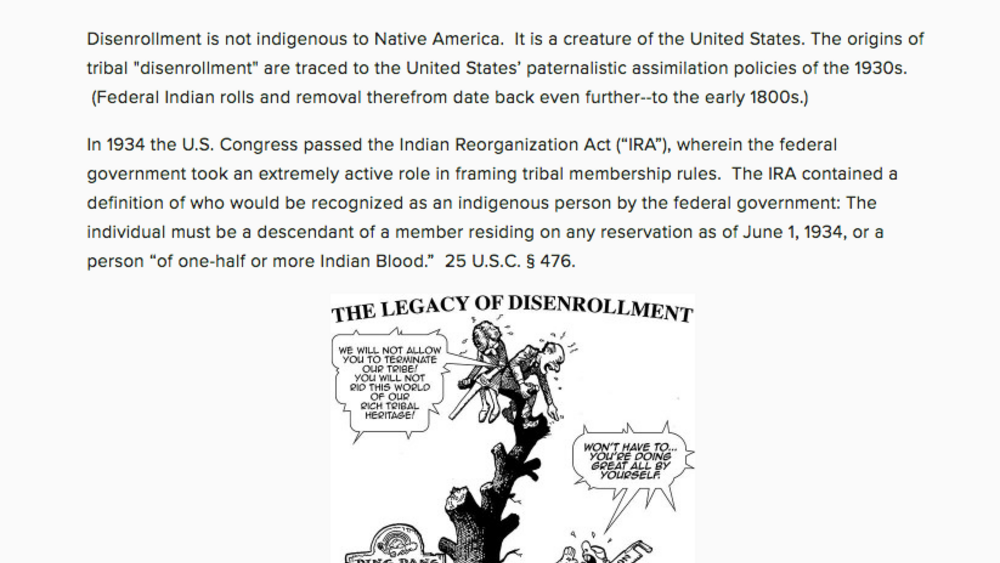

An Essay on the Federal Origins of Disenrollment

Disenrollment is not indigenous to Native America. It is a creature of the United States. The origins of disenrollment are traced to the United States’ paternalistic assimilation policies of the 1930s. In 1934 the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (“IRA”), wherein the federal…

A Legal History of Blood Quantum in Federal Indian Law to 1935

The paper traces the development of the use of blood quantum, or fractional amounts of Indian blood to define Indian in federal law up to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. The paper shows that blood quantum was not widely used in federal law until the twentieth century, as the branches of the…

Navajo Cultural Identity: What can the Navajo Nation bring to the American Indian Identity Discussion Table?

American Indian identity in the twenty-first century has become an engaging topic. Recently, discussions on Ward Churchilla's racial background became a hotbed issue on the national scene. A few Native nations, such as the Pechanga and Isleta Pueblo, have disenrolled members. Scholars such as Circe…

An Anishinaabe Tribalography: Investigating and Interweaving Conceptions of Identity During the 1910s on the White Earth Reservation

This article explores the varied ways in which the Anishinaabeg of White Earth defined themselves during the early twentieth century. It consists of two primary parts. In part 1 I go beyond the artifacts in order to enliven the history, to offer an alternative way of remembering the past. In…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …