Indigenous Governance Database

cultural preservation

Immersion School is Saving a Native American Language

The White Clay Immersion School on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Harlem, Montana is trying to save the A’ani language. Thanks to the school’s efforts 26 students, a record for the school, are currently studying the Native American language...

A Place Called Poarch Podcast

The Poarch Creek Indians produced a 24-episode podcast (March 2022-December 2023) covering a variety of nation-building topics including tribal lands, sovereignty, property rights, and more.

SEEDocs - Owe'neh Bupingeh Preservation Plan and Rehabilitation Project

Re-creating a more vital Pueblo center and reinvigorating cultural heritage traditions through the rehabilitation of the historic Pueblo core was this project's focus. The Pueblo core is the spiritual, social and cultural center of the Pueblo. Community members were trained in traditional building…

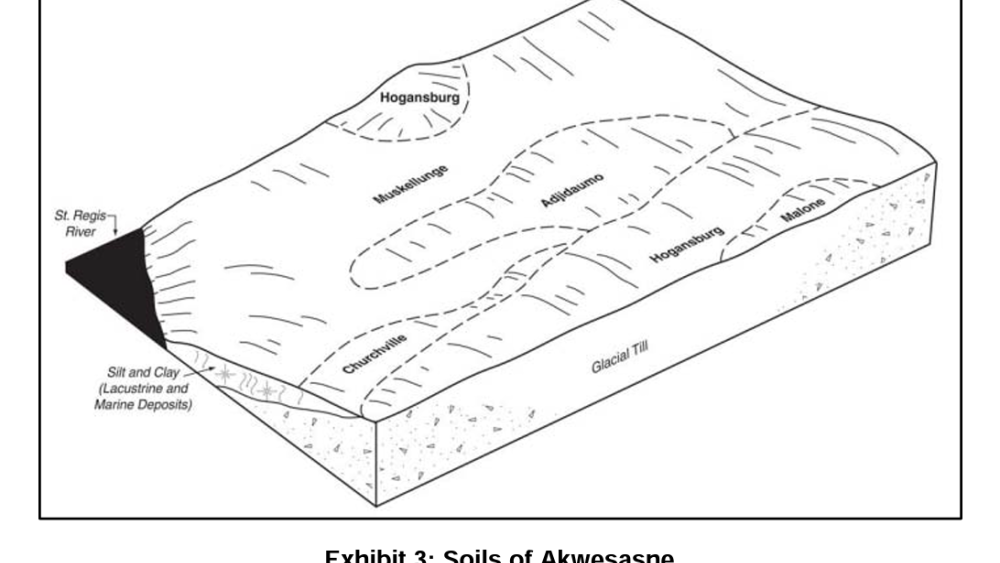

Climate Change Adaptation Plan for Akwesasne

The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe’s (SRMT) Environment Division is investigating the impacts of climate change on the resources, assets, and community of Akwesasne and is developing recommendations for actions to adapt to projected climate change impacts. This plan is a first step in an effort to…

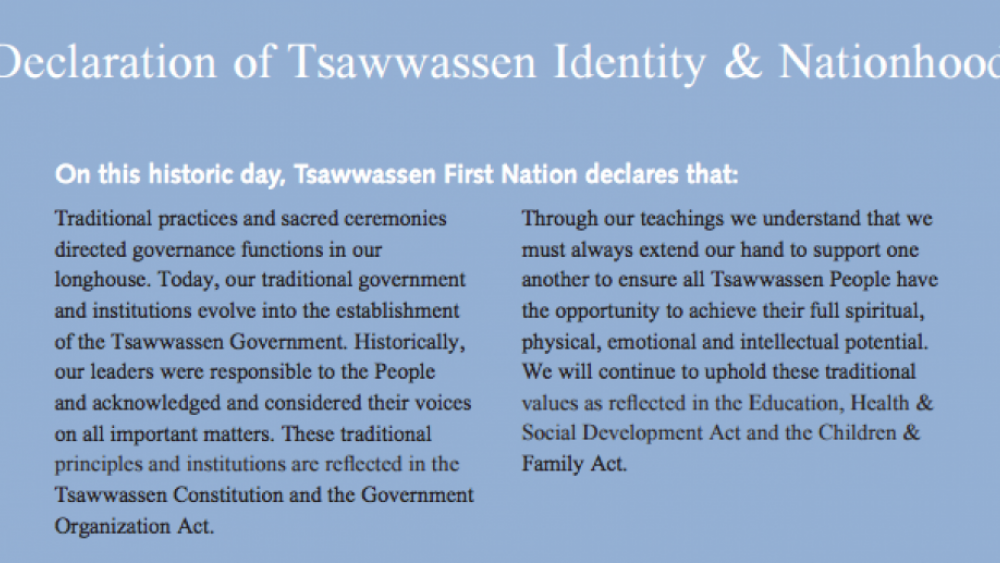

Declaration of Tsawwassen Identity & Nationhood

We are Tsawwassen People "People facing the sea", descendants of our ancestors who exercised sovereign authority over our land for thousands of years. Tsawwassen People were governed under the advice and guidance of leaders, highborn women, headmen, and speakers through countless generations...

Best Practices Case Study (Economic Realization): Osoyoos Indian Band

The Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) is located in the interior of British Columbia. They are a member community of the Okanagan Nation Alliance. The Band was formed in 1877 and is home to about 370 on-reserve band members. The goal of the OIB is to move from dependency to a sustainable economy like that…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …