Indigenous Governance Database

decision making

Indigenous Land Management in the United States: Context, Cases, Lessons

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is seeking ways to support First Nations’ economic development. Among its concerns are the status and management of First Nations’ lands. The Indian Act, bureaucratic processes, the capacities of First Nations themselves, and other factors currently limit the…

Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission's Treaty Rights/National Forest MOU

The Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), a tribally chartered intertribal agency, negotiated a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the US Forest Service that both recognizes and implements treaty-guaranteed hunting, fishing, and gathering rights under tribal regulations and…

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Learning to Make Informed Decisions"

Native leaders share what the role of a leader entails from studying the history of the tribe to listening to and learning from elders of the community; all the tools necessary to making informed decisions.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "The Importance of Strategic Planning"

Native leaders explain the importance of strategic thinking and planning to effective Native nation governance and emphasize the consideration of future generations in Native nations' decision-making processes.

Jaime Pinkham: How Do You Hit the Ground Running?: Strategies for Handling the Load and Forging Ahead

Former Nez Perce Tribal Treasurer Jaime Pinkham speaks about his experience as a leader of his nation and what it takes to "hit the ground running" when one assumes a leadership role.

Ned Norris, Jr.: Perspectives on Leadership and Nation Building

Tohono O'odham Nation Chairman Ned Norris, Jr. speaks to aspiring and current Native nation leaders about the keys to being an effective leader and shares his personal experiences in preparing to become the leader of his nation.

Back to Our Path is not a Trip Backward

Many of us are familiar with our expression Ohnkwe Ohnwe. It is what we use to describe ourselves as the original people of Turtle Island. The approximate translation is “real human being, forever.” There was never any question that we had a future. We were never tied to a spot on a timeline. We…

Indigenous Nations Have the Right to Choose: Renewal or Contract

When making significant change Indigenous nations make choices about whether to build on traditions or to adopt new forms of government, economy, culture or community. Many changes are external and often forced upon contemporary Indigenous Peoples. Adapting to competitive markets, or new…

Kin-Based Governments Can Be Successful and Profitable

A key to understanding American Indian nations, and Indigenous Peoples in general, is local community organization. Local groups, as basic building blocks of indigenous nations, play a powerful role in tribal or national consensus building and decision-making. The ways that local indigenous groups…

How Does Tribal Leadership Compare to Parliamentary Leadership?

Many traditional American Indian governments have significant organizational similarities with contemporary parliamentary governments around the world. A key similarity is that leadership serves only as long as there is supporting political consensus or confidence that the leader or leadership…

Guatemala’s Indigenous Women in Resistance: On the Frontline of the Community’s Struggle to Defend Mother Earth and her Natural Assets

The objective of this study is to examine the social process at work in the defense of natural resources from the perspective of the indigenous women involved in it. Given the country’s broad cultural diversity and the time limits for completing this report, we assumed right from the start that it…

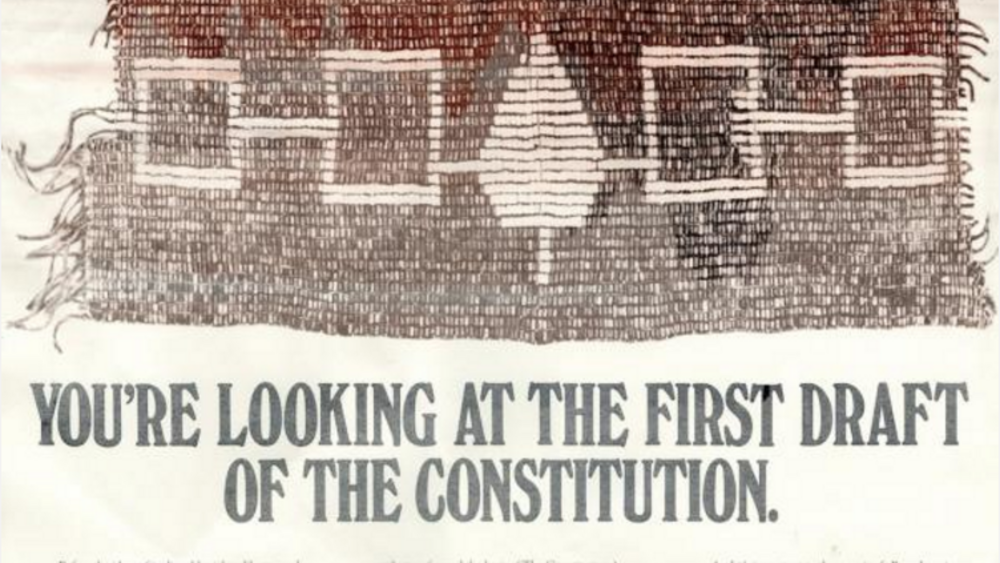

Wolves Have A Constitution: Continuities in Indigenous Self-Government

This article is about constitutionalism as an Indigenous tradition. The political idea of constitutionalism is the idea that the process of governing is itself governed by a set of foundational laws or rules. There is ample evidence that Indigenous nations in North America–and in Australia and New…

On Improving Tribal-Corporate Relations In The Mining Sector: A White Paper on Strategies for Both Sides of the Table

Mining everywhere is inherently controversial. By its very nature, it poses hard economic, environmental, and social tradeoffs. Depending on the nature of the resource and its location, to greater or lesser degrees, the mining process necessarily disturbs environments, alters landscapes, and…

Community-Led Development

The purpose of this paper is to explore the concept and practice of community-led development. It is an approach to tackling local problems that is taking hold throughout the world. While its expression may vary depending upon the community and the specific area of focus, there are nonetheless some…

Best Practices Case Study (Participation in Decision Making): Gila River Indian Community

Gila River Indian Community, which borders the Arizona cities of Tempe, Phoenix, Mesa, and Chandler, has nearly 17,000 tribal citizens. Half of the population is younger than 18. Like youth elsewhere, Gila River youth are challenged by a host of problems. Gang violence, drug and alcohol abuse, and…

Best Practices Case Study (Inter-Governmental Relations): Squamish & Lil'wat First Nations

The Squamish First Nation and the Lil'wat First Nation are both located in southwestern B.C. and have an area of overlapping traditional territory that extends into the lands around the resort community of Whistler. Although they are two distinct First Nations with different cultures and social…