Indigenous Governance Database

economic impact

Place Based Economic Development and Tribal Casinos

Tribal lands in the U.S. have historically experienced some of the worst economic conditions in the nation. We review some existing research on the effect of American Indian tribal casinos on various measures of local economic development. This is an industry that began in the early 1990s and…

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 7: Direct Relief for Tribal Citizens: Getting beyond Per Caps

From setting tribal priorities to building infrastructure to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

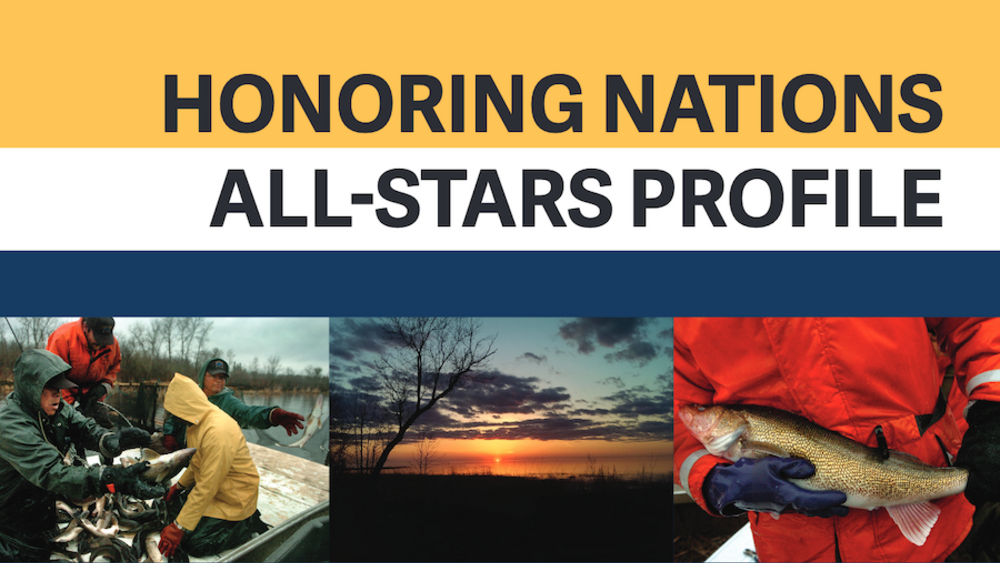

Honoring Nations All-Stars Profile: The Red Lake Walleye Recovery Program

In 1997, the members of the Red Lake Fisheries Association (RLFA), a cooperative established by com-mercial fishermen from the Red Lake Nation,1 voted to discontinue all commercial gillnet fishing on Red Lake for the upcoming season. An overwhelming majority of the RLFA’s members supported the…

Policy Brief: Emerging Stronger than Before: Guidelines for the Federal Role in American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes’ Recovery from the COVID‐19 Pandemic

The COVID‐19 pandemic has wrought havoc in Indian Country. While the American people as a whole have borne extreme pain and suffering, and the transition back to “normal” will be drawn out and difficult, the First Peoples of America arguably have suffered the most severe and most negative…

Native Nation Building and the CARES Act

On June 10, 2020 the Native Nations Institute hosted an a online panel discussion with Chairman Bryan Newland of the Bay Mills Indian Community, Councilwoman Herminia Frias of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, and hosted by Karen Diver the former Chair of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and…

Policy Brief: The Need for a Significant Allocation of COVID‐19 Response Funds to American Indian Nations

This policy brief addresses the impact of the current COVID‐19 crisis on American Indian tribal economies, tribes’ responses to the crisis, and the implications of these impacts and actions for the US government’s allocation of crisis‐response funds to federally recognized tribes. We conclude that…

Harvard Project: COVID-19 Resources for Indian Country Toolbox

As the country responds to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the task before tribal nations is complicated by many unknowns. The Harvard Project recognizes the challenges you're up against and we want to help. We are not experts in the health consequences of the pandemic, but we are monitoring…

Chairman Dave Archambault II: Laying the Foundation for Tribal Leadership and Self-governance

Chairman Archambault’s wealth and breadth of knowledge and experience in the tribal labor and workforce development arena is unparalleled. He currently serves as the chief executive officer of one of the largest tribes in the Dakotas, leading 500 tribal government employees and overseeing an array…

Social and Economic Consequences of Indian Gaming in Oklahoma

Much has been written in the mainstream press about Indian gaming and its impact on Indian and non-Indian communities. The debate, however, tends to be focused on Class III or “casino-style” gaming. The effects of Class II gaming have largely been overlooked by the press and, unfortunately, by the…

Eileen Briggs: The Importance of Data and Community Engagement

Eileen Briggs is a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and is the Executive Director of Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Ventures. She is also the Principal Investigator on "Cheyenne River Voices Research" — a reservation-wide research project including a household survey of over…

Honoring Nations: John McCoy: Intergovernmental Relations

John McCoy of the Tulalip Tribes offers advice to session participants about how to communicate tribal priorities in the intergovernmental law and policy arenas.

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne and Federal Bridge Corporation Limited Sign Memorandum of Understanding for North Channel Bridge

The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (MCA) announced that it has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Federal Bridge Corporation Limited (FBCL) for a new bridge that will cross the North Channel of the St. Lawrence River between Kawehnoke (Cornwall Island) and the City of Cornwall.…

How Does Household Income Affect Child Personality Traits and Behaviors?

Existing research has investigated the effect of early childhood educational interventions on the child's later-life outcomes. These studies have found limited impact of supplementary programs on children's cognitive skills, but sustained effects on personality traits. We examine how a positive…

Betting on a School

Ninety miles east of downtown Los Angeles in the San Bernardino Mountains, a school for Native American children peers down onto its main benefactor, a glittering, Las Vegas-style casino and hotel owned and operated by the Morongo Band of Mission Indians. Millions of dollars spent in the casino by…

The Economic and Fiscal Impacts of Indian Tribes in Washington

The economies of Washington’s Indian reservations have grown over the last half-decade, and despite some complaints to the contrary, Washington taxpayers have little to fear and much to gain from American Indian economic development. The evidence points to strong net benefits for Indians and non-…