Indigenous Governance Database

ethics

Gugu Badhun Sovereignty Sundays: An adaptable online Indigenous nation-building method

Nation-building research is a flexible approach to research that prioritises the voices and self-determination agendas of Indigenous Nations. This paper discusses our application of the Indigenous nation-building (INB) methodology in our research with Gugu Badhun Aboriginal Nation, Australia,…

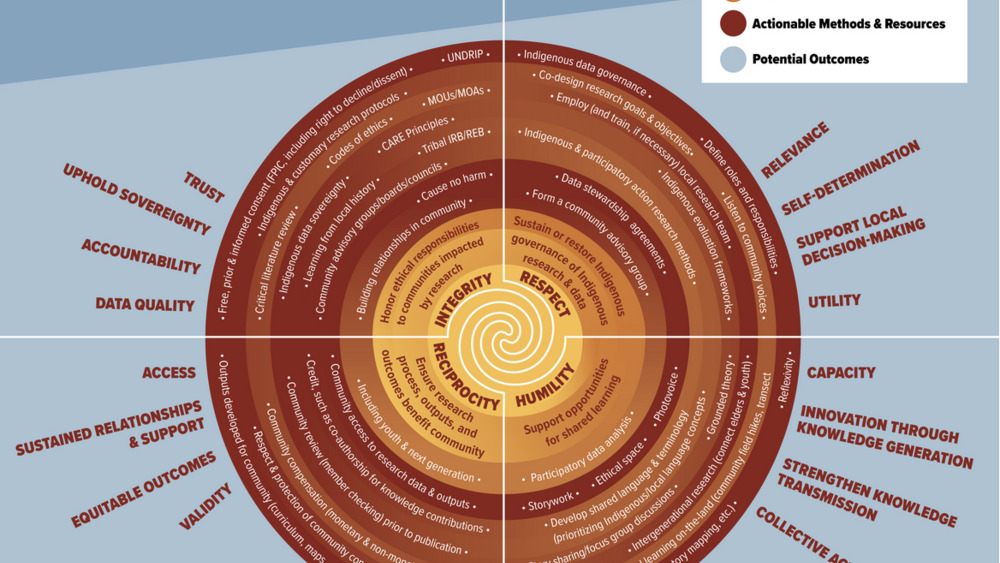

A values-centered relational science model: supporting Indigenous rights and reconciliation in research

Addressing complex social-ecological issues requires all relevant sources of knowledge and data, especially those held by communities who remain close to the land. Centuries of oppression, extractive research practices, and misrepresentation have hindered balanced knowledge exchange with Indigenous…

Improving Ethical Practice in Transdisciplinary Research Projects Webinar

Transdisciplinary research, or research conducted by people from different disciplines and organizations working together to solve a common problem, holds promise for communities and scientists seeking to address complex socio-ecological problems like climate change. However, this collaborative…

Expanded Ethical Principles for Research Partnership and Transdisciplinary Natural Resource Management Science

Natural resource researchers have long recognized the value of working closely with the managers and communities who depend on, steward, and impact ecosystems. These partnerships take various forms, including co-production and transdisciplinary research approaches, which integrate multiple…

Indigenous Data Sovereignty: The CARE Principles and the Biocultural Labels Initiative

The NYU Alliance for Public Interest Technology Alliance is a dynamic and multidisciplinary group of NYU faculty who are experts on the responsible and ethical creation, use and governance of technology in society. The Alliance is a provostial initiative that connects numerous NYU hubs and…

Genomic Research Through an Indigenous Lens: Understanding the Expectations

Indigenous scholars are leading initiatives to improve access to genetic and genomic research and health care based on their unique cultural contexts and within sovereign-based governance models created and accepted by their peoples. In the past, Indigenous peoples’ engagement with genomic research…

LeRoy Staples Fairbanks III: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Leroy Staples Fairbanks III, who serves on the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe Council, discusses some of the hard stances he had to take in order to do his job well and also shares an overview of some of the major steps thatthe leech Lake Band has taken in order to govern more effectively and use its…

Patricia Zell: Addressing Tough Governance Issues

Former U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel Patricia Zell share some effective strategies for educating and lobbying members of the U.S. Congress, based on her many years of experience working for the U.S. Senate on Committee on Indian Affairs.

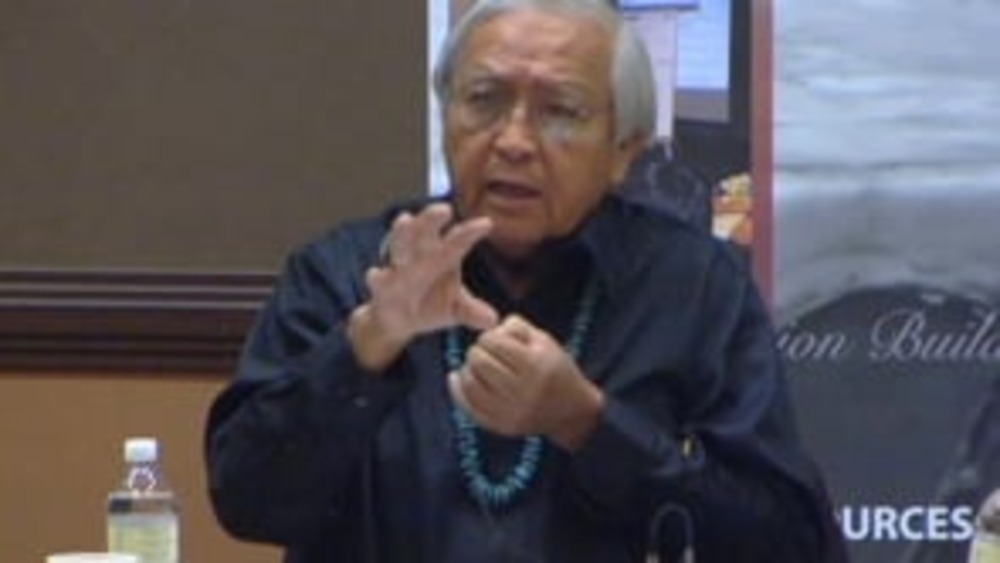

Peterson Zah: Addressing Tough Governance Issues

Former Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah shares the personal ethics he practiced while leading his nation, and discusses how he learned those ethics from his family and other influential figures in his life.