Indigenous Governance Database

financial management

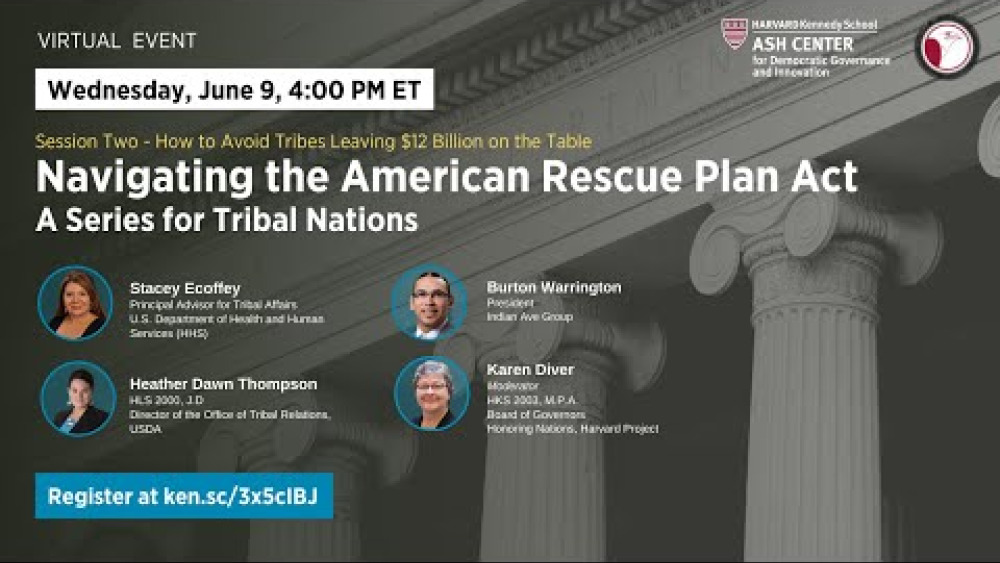

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 2: How Tribes Can Avoid Leaving $12 Billion on the Table

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides the largest single infusion of federal funding into Indian Country in the history of the United States. More than $32 billion is directed toward assisting American Indian nations and communities as they work to end and recover from the devastating COVID-…

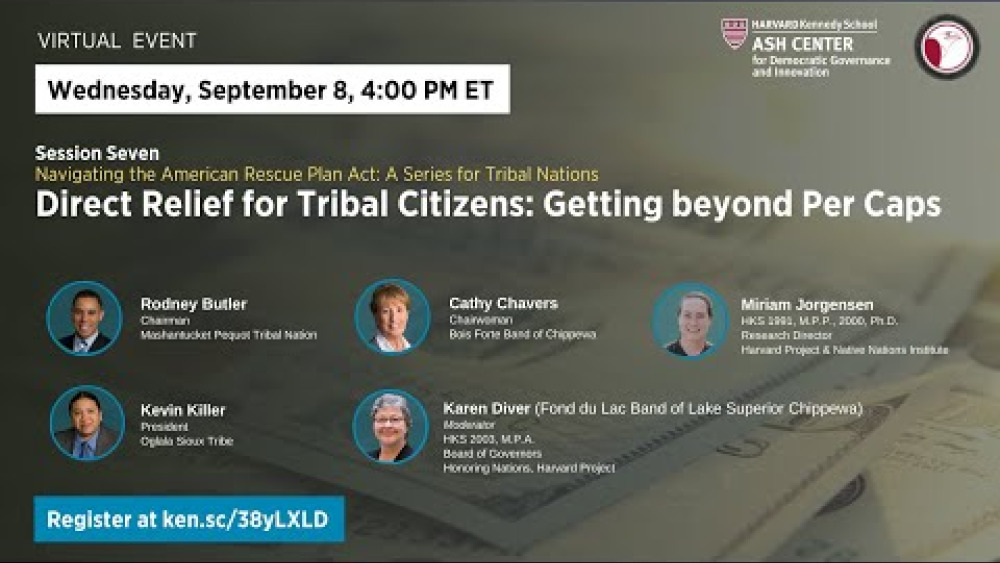

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 7: Direct Relief for Tribal Citizens: Getting beyond Per Caps

From setting tribal priorities to building infrastructure to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

Bad with Money Podcast: COVID's Economic Devastation on Tribal Lands

Gaby Dunn speaks with Karen R. Diver (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), Director of Business Development for the Native American Advancement Initiatives at the Native Nations Institute and appointee of President Obama as the Special Assistant to the President for Native American Affairs…

Tribal Leaders Handbook on Homeownership

As Native populations grow rapidly, tribal leaders are challenged as never before to provide their members decent housing. Expanding homeownership is a huge part of the solution for reservations and Indian areas, but until recently lenders just didn't extend home loans in Indian Country. The …

Adam Geisler: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Adam Geisler, Secretary of the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians, discusses the diverse set of challenges he faces as an elected leader of his nation and discusses some of the innovative ways that he, his leadership colleagues, and his nation have worked to overcome those challenges. He…

Honoring Nations: Miriam Jorgensen: Using Your Human and Financial Resources Wisely

NNI Research Director Miriam Jorgensen kicks off the 2004 Honoring Nations symposium with a discussion focused on "Using Your Human and Financial Resources Wisely," In her presentation, she frames key issues and highlights the ways that successful tribal government programs have attracted…

Terrance Paul: Building Sustainable Economies: Membertou First Nation

Chief Terrance Paul shares the keys to a sustainable economy through examples from the Membertou First Nation.

Elderly Protection Teams Work to Stop Abuse

While more than 30 tribal governments across the country have implemented elder abuse codes, some Indian communities and concerned citizens have taken a more proactive role to ensure these laws are enforced. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council started the first Elderly Protection Team in Indian…

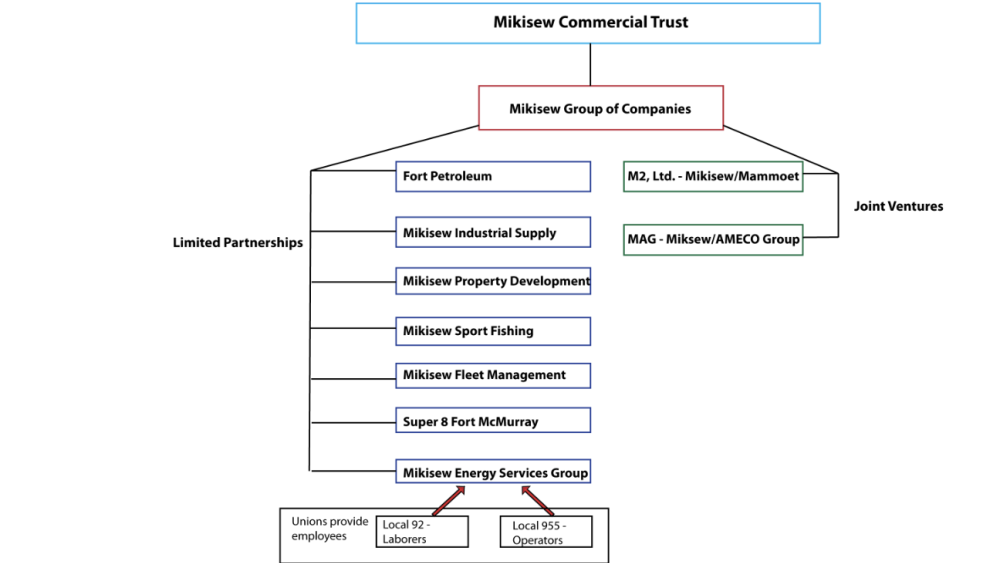

Forwarding First Nation Goals Through Enterprise Ownership: The Mikisew Group Of Companies

The Mikisew Group of Companies (Mikisew Group) is the business arm of the Mikisew Cree First Nation (MCFN). Founded in 1991 using monies from a $26.6 million land claim settlement with the governments of Alberta and Canada, it has achieved remarkable success. This success is evident in the wide…