Indigenous Governance Database

Indian Reorganization Act (IRA)

Tribes across the country are re-examining their constitutions

Erma Vizenor is not exactly a revolutionary. But like America’s founders, she’s on a mission to ratify a new constitution in her homeland – the White Earth tribal nation. Most Americans don’t realize that tribes have their own constitutions, which set down rules for everything from tribal…

Tim Giago: Was the Indian Reorganization Act good or bad?

It was 75 years ago on June 18, 1934 when the Indian Reorganization Act became the law of the land. On the 50th anniversary of the IRA, a conference was held at Sun Valley, Idaho to talk about the good and the bad of the Act. On the 75th birthday of the Act, there was nothing but silence. Has…

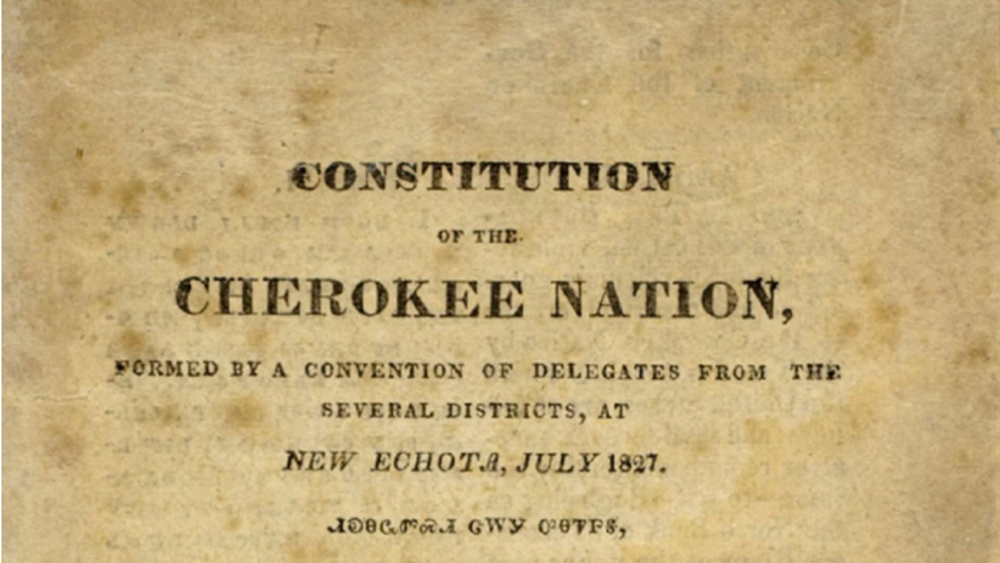

Tribal Constitutions

Modern tribal nations pass laws, exercise criminal jurisdiction, and enjoy extensive powers when it comes to self-governance and matters of sovereignty. And of 566 tribal nations, just under half have adopted written constitutions. In the American tradition, a constitution limits the power yielded…

Indian Pride: Episode 112: Tribal Government Structure

This episode of the "Indian Pride" television series, aired in 2007, chronicles the governance structures of several Native nations in an effort to show the diversity of governance systems across Indian Country. It also features an interview with then-chairman Harold "Gus" Frank of the…

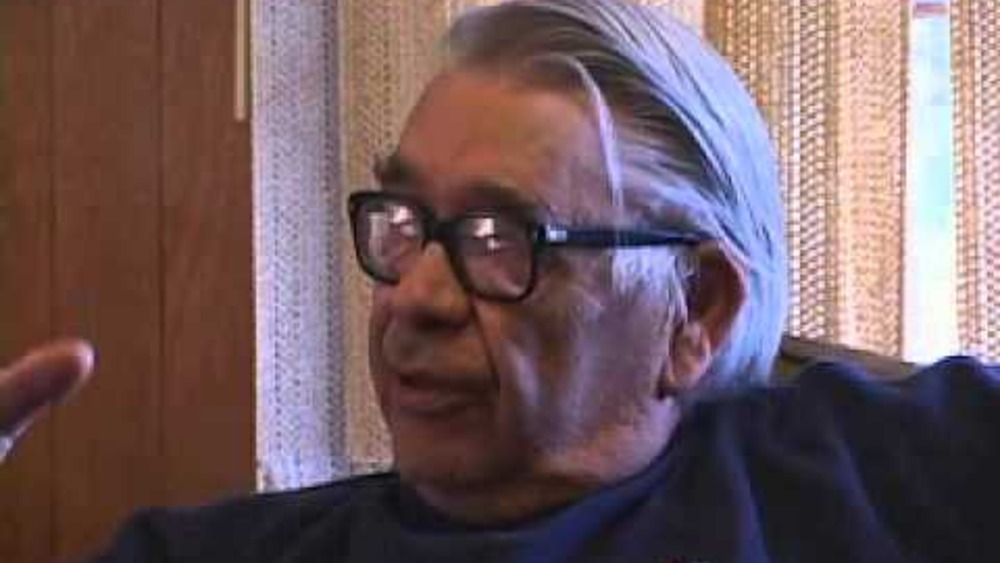

Vine Deloria's Last Video Interview

American Indian author, theologian, historian, and activist Vine Deloria, Jr. (1933-2005) talks with documentary film producer Grant Crowell about traditional Indigenous governance systems and criteria for citizenship, the impact of colonial policies on tribal citizenship (specifically the effects…

Truth To Tell: Community Connections - White Earth Constitutional Forum Part I

In collaboration with production partner KKWE/Niijii Radio, TruthToTell and CivicMedia/Minnesota traveled west on August 14, 2013, to the White Earth Reservation to air/televise the seventh in our series of LIVE Community Connections forums on critical Minnesota issues. Convened at White Earth's…

Truth To Tell: Community Connections - White Earth Constitutional Forum Part II

In collaboration with production partner KKWE/Niijii Radio, TruthToTell and CivicMedia/Minnesota traveled west on August 14, 2013, to the White Earth Reservation to air/televise the seventh in our series of LIVE Community Connections forums on critical Minnesota issues. Convened at White Earth's…

Joseph P. Kalt: The Nation-Building Renaissance in Indian Country: Keys to Success

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Joseph P. Kalt presents on the Native nation-building renaissance taking root across in Indian Country, and shares some stories of success.

An Essay on the Modern Dynamics of Tribal Disenrollment

Disenrollment is predominately about race, and money, and an “individualistic, materialistic attitude” that is not indigenous to tribal communities. Because many tribes have maintained the IRA’s paternalistic and antiquated definition of “Indian” vis-a-vis blood quantum (as discussed in “An Essay…

Rethinking Rewriting: Tribal Constitutional Amendment and Reform

This essay examines the recent wave of American Indian tribal constitutional change through the framework of subnational constitutional theory. When tribes rewrite their constitutions, they not only address internal tribal questions and communicate tribal values, but also engage with other…

Northern Cheyenne Tribe: Traditional Law and Constitutional Reform

This profile by Sheldon C. Spotted Elk examines the U.S. government's infringement on the Northern Cheyenne's political sovereignty. Most significantly, it examines the relationship between the oral history of the Northern Cheyenne and its impact on traditional tribal governance and law. Following…

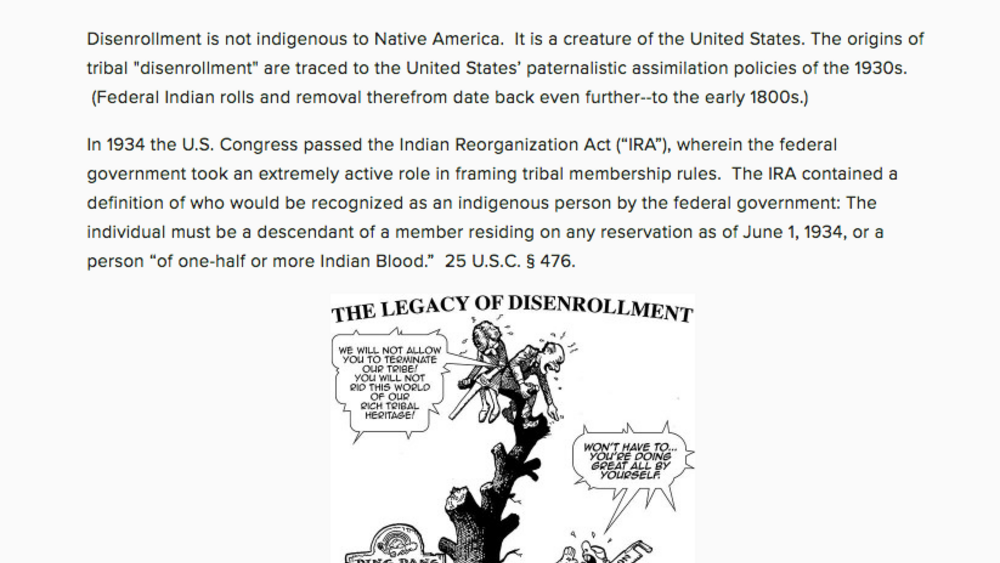

An Essay on the Federal Origins of Disenrollment

Disenrollment is not indigenous to Native America. It is a creature of the United States. The origins of disenrollment are traced to the United States’ paternalistic assimilation policies of the 1930s. In 1934 the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (“IRA”), wherein the federal…

Race and American Indian Tribal Nationhood

This article bridges the gap between the perception and reality of American Indian tribal nation citizenship. The United States and federal Indian law encouraged, and in many instances mandated, Indian nations to adopt race-based tribal citizenship criteria. Even in the rare circumstance where an…

Tribal Economic Development: Nuts & Bolts

Tribal economic development is a product of the need for Indian tribes to generate revenue in order to pay for the provision of governmental services. Unlike the federal government or states, Indian tribes – in general – have no viable tax base from which to generate revenues sufficient to…

Legal Pluralism and Tribal Constitutions

What do pigs roaming the streets of New York City during the first half of the nineteenth century and tribal constitutions have in common? The most obvious (and often the most correct) answer is, undoubtedly, “absolutely nothing.” However, tribal advocates, particularly those concerned with the…

Tribal Constitutions and Native Sovereignty

More than 565 Indigenous tribal governments exercise extensive sovereign and political powers within the United States today. Only about 230 of the native communities that created these governments, however, have chosen to adopt written constitutions to define and control the political powers of…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …