Indigenous Governance Database

managing growth

NNI Indigenous Leadership Fellow: Jamie Fullmer (Part 1)

Jamie Fullmer, former chairman of the Yavapai-Apache Nation, discusses the importance of the development of capable governing institutions to Native nations' exercise of sovereignty, and provides an overview of the steps that he and his leadership colleagues took to develop those institutions…

Deron Marquez: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Former San Manuel Band of Mission Indians Chairman Deron Marquez reflects on his experience as the chief executive of his nation, from his unexpected return to the reservation to building a sustainable economy essentially from scratch.

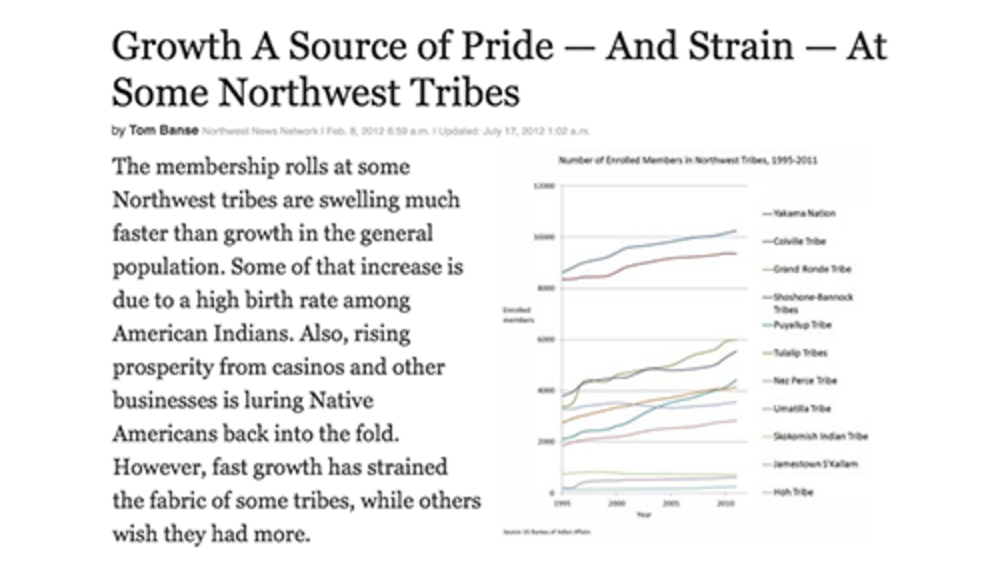

Growth a Source of Pride - And Strain - At Some Northwest Tribes

The membership rolls at some Northwest tribes are swelling much faster than growth in the general population. Some of that increase is due to a high birth rate among American Indians. Also, rising prosperity from casinos and other businesses is luring Native Americans back into the fold. However,…