Indigenous Governance Database

nation-owned enterprises

Indian Pride: Episode 108: Economic Development

This episode of the "Indian Pride" television series, aired in 2007, explores the economic development efforts of selected Native nations cross Indian Country. It also features an interview with Lance Morgan, CEO of the Winnebago Trib'es Ho-Chunk, Inc., who provides an overview of the evolution of…

The Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

This video, produced by the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, provides a brief overview of the nation's history, from its push to achieve federal recognition to its efforts to create a diversified, sustainable economy.

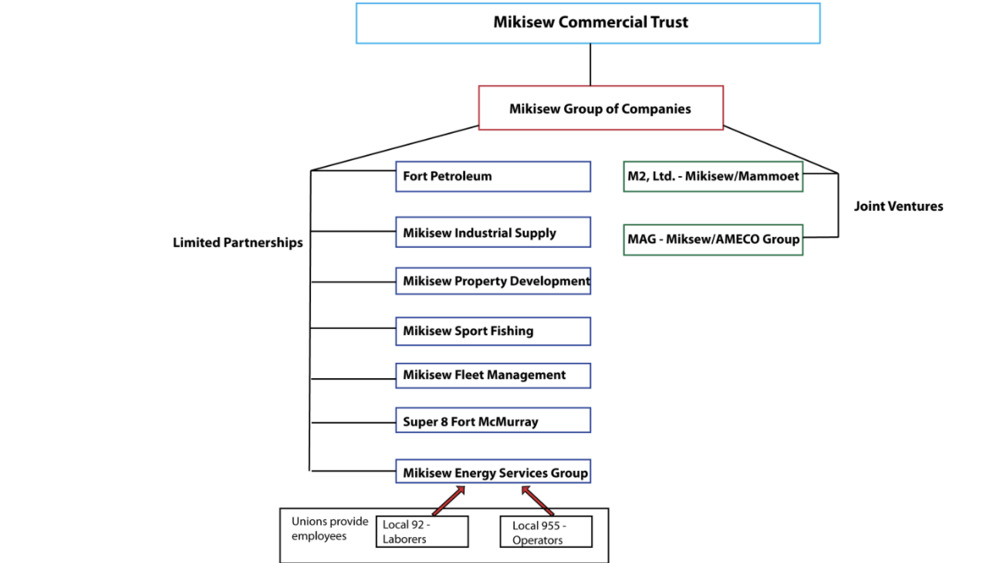

Forwarding First Nation Goals Through Enterprise Ownership: The Mikisew Group Of Companies

The Mikisew Group of Companies (Mikisew Group) is the business arm of the Mikisew Cree First Nation (MCFN). Founded in 1991 using monies from a $26.6 million land claim settlement with the governments of Alberta and Canada, it has achieved remarkable success. This success is evident in the wide…

Journey to Economic Independence: B.C. First Nations' Perspectives

There are two approaches to economic development being pursued by the participant First Nations. One is creation of an economy through support for local entrepreneurs and the development of their individual enterprises (i.e. Westbank First Nation). The other is creation of an economy through…

First Nations Economic Development: The Meadow Lake Tribal Council

A new approach to economic development is emerging among the First Nations in Canada. This approach emphasizes the creation of profitable businesses competing in the global economy. These businesses are expected to help First Nations achieve their broader objectives that include: (i) greater…

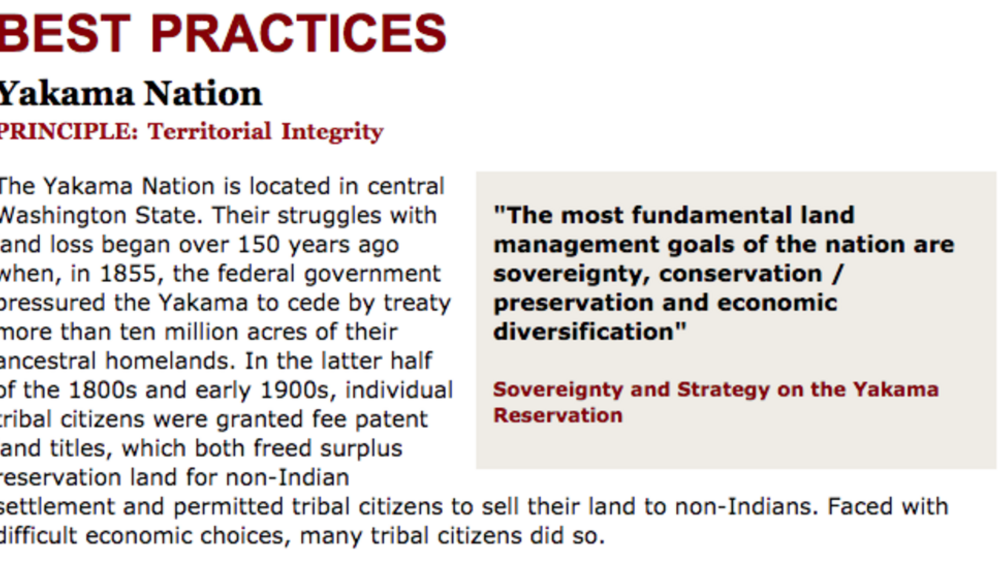

Best Practices Case Study (Territorial Integrity): Yakama Nation

The Yakama Nation is located in central Washington State. Their struggles with land loss began over 150 years ago when, in 1855, the federal government pressured the Yakama to cede by treaty more than ten million acres of their ancestral homelands. In the latter half of the 1800s and early 1900s,…

Best Practices Case Study (Economic Realization): Osoyoos Indian Band

The Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) is located in the interior of British Columbia. They are a member community of the Okanagan Nation Alliance. The Band was formed in 1877 and is home to about 370 on-reserve band members. The goal of the OIB is to move from dependency to a sustainable economy like that…

What Determines Indian Economic Success? Evidence from Tribal and Individual Indian Enterprises

Prior analysis of American Indian nations' unemployment, poverty, and growth rates indicates that poverty in Indian Country is a problem of institutions particularly political institutions, not a problem of economics per se. Using unique data on Indian-owned enterprises, this paper sheds light on…

Securing Our Futures

NCAI is releasing a Securing Our Futures report in conjunction with the 2013 State of Indian Nations. This report shows areas where tribes are exercising their sovereignty right now, diversifying their revenue base, and bringing economic success to their nations and surrounding communities. The…

Tribal Economic Development: Nuts & Bolts

Tribal economic development is a product of the need for Indian tribes to generate revenue in order to pay for the provision of governmental services. Unlike the federal government or states, Indian tribes – in general – have no viable tax base from which to generate revenues sufficient to…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …