Indigenous Governance Database

policy development

CARE Directs Us Home: Reclaiming Indigenous Authority Over Data

In 2019, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) developed and published the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics) to complement the FAIR principles for open scientific data management (Findable, Accessible,…

Steps for Conducting Research and Evaluation in Native Communities

Research and evaluation studies in Native communities have been characterized by mistrust and misrepresentation. Most of these missteps are the result of actions by researchers with little or no experience working with Native governments, Native communities, or Native American people. Research has…

Common Rule Revisions to Govern Machine Learning on Indigenous Data: Implementing the Expectations

We agree with Chapman et al. that the Common Rule needs revision, particularly regarding the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) in health research with Indigenous Peoples. Without greater consideration of collective harms in human subjects research, this…

Aligning policy and practice to implement CARE with FAIR through Indigenous Peoples’ protocols

In 2019, members of the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) published the CARE Principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics) for Indigenous Data Governance (IDGov). CARE has since been referenced, leveraged, and adopted in various ways across disciplines and…

Indigenous Data Governance Brief

This Brief reports on the “Tribal Leaders and Indigenous Scholars Workshop” and the “Action Planning and Forward Thinking Session” held at the Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance Summit convened by the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network (USIDSN) on the lands of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe and…

Indigenous Data Governance and Universities Communiqué

Universities create, use, and hold enormous amounts of Indigenous data. These data range from old historical records to contemporary large datasets, including Open Data2 and the data underpinning emerging Artificial Intelligence (AI) Technologies. Indigenous Peoples’ data include information about…

Determi-Nation podcast with Darrah Blackwater

Determi-Nation is a series of conversations with Indigenous people doing incredible things to strengthen sovereignty and self-determination in their communities.

Uniform Commercial Codes: Bringing Business to Indian Country. Tribal Secured Transactions Laws: A Working Forum

During "Uniform Commercial Codes: Bringing Business to Indian Country", a conference on January 15, 2013, sponsored by The Federal Reserve Banks of Minneapolis, Kansas City, and San Francisco and the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Office of Indian Energy and Economic Development, Susan Woodrow…

Indigenous Peoples' Data During COVID-19: From External to Internal

Global disease trackers quantifying the size, spread, and distribution of COVID-19 illustrate the power of data during the pandemic. Data are required for decision-making, planning, mitigation, surveillance, and monitoring the equity of responses. There are dual concerns about the availability and…

Working with the CARE Principles: operationalising Indigenous data governance

Shifting the focus of data governance from consultation to values-based relationships to promote equitable Indigenous participation in data processes. Indigenous data sovereignty is becoming an increasingly relevant topic, as limited opportunities for benefit sharing have focused attention on the…

Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Policy

This book examines how Indigenous Peoples around the world are demanding greater data sovereignty, and challenging the ways in which governments have historically used Indigenous data to develop policies and programs. In the digital age, governments are increasingly dependent on data and data…

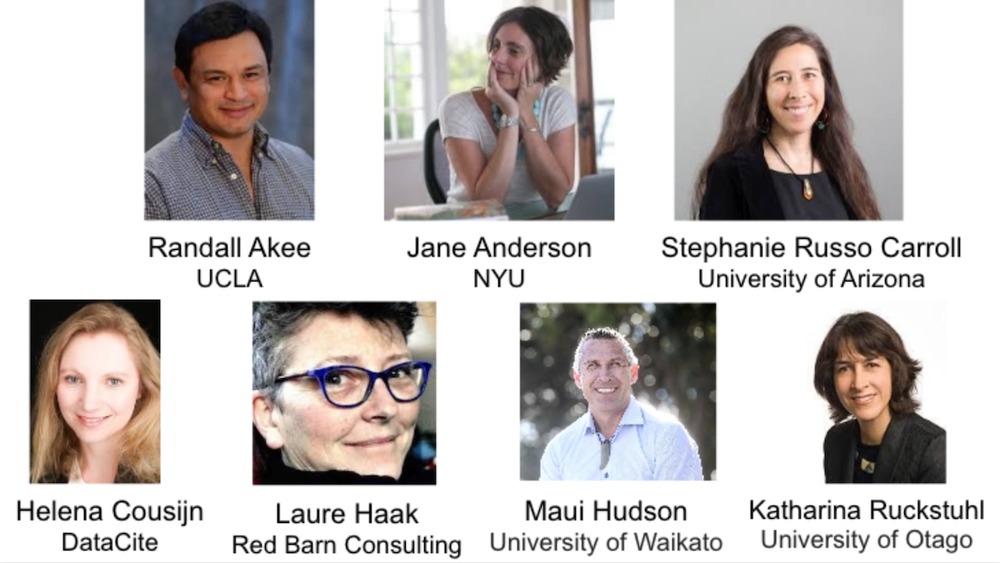

Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Activating Policy and Practice

The Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA), the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network (USIDSN), and ORCID invite you to join us for a webinar about Global Indigenous Data Alliance Policy Interaction. We have asked three panelists to speak about their experiences with Indigenous Data Sovereignty;…

Joseph Flies-Away: Knowing, Living and Defending the Rule of Law

Joseph Flies-Away (Hualapai), Associate Justice of the Hualapai Nation Court of Appeals, discusses the importance of Native nations building and living a sound, culturally sensible rule of law -- through constitutions, codes, common law and in other ways -- that everyone in those nations knows,…

Jamie Fullmer, Rebecca Miles and Darrin Old Coyote: Our Leadership Experiences, Challenges, and Advice (Q&A)

Jamie Fullmer (former Chairman of the Yavapai-Apache Nation), Rebecca Miles (Executive Director and former Chairwoman of the Nez Perce Tribe) and Darrin Old Coyote (Chairman of the Crow Tribe) field questions from seminar participants about how they have negotiated the fundamental challenges of…

Catalina Alvarez: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Vice Chairwoman of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe Catalina Alvarez shares what she wishes that she knew before she first took office, and focuses on the importance of elected leaders understanding -- and confining themselves to performing -- their appropriate roles and responsibilities.