Indigenous Governance Database

self-determination

Indian Self-Determination and Sovereignty

If ever a concept grabbed hold of hearts and minds in Indian country in the past couple decades surely it would be that of sovereignty. Native people talk about it with reverence, demanding that it be respected by the federal government, and expect their tribal governments to assert it. Even the…

Grand Council Chief Patrick Madahbee: NFN Gichi-Naaknigewin

Anishinabek Nation Grand Council Chief Patrick Wedaseh Madahbee speaks to Nipissing First Nation members about the importance of the Gichi-Naaknigewin (Constitution) and its relationship to community development.

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development and its Application to Canadian Aboriginal Business

This lecture is part of a course Stephen Cornell is teaching in Simon Fraser University's Executive MBA in Aboriginal Business and Leadership program. A panel of three joined Dr. Cornell in a discussion about the building of First Nation economies and the role citizen entrepreneurship can play in…

Our Journey - Our Choice - Our Future: Maa-nulth Treaty Legacy

On April 1, 2011, the Maa-nulth First Nations completed what has been a long journey to self-determination. It was an historic day for all, and a day of celebration for the Huu-ay-aht, Ka:’yu:’k't’h/Che:k’tles7et’h, Toquaht, Uchucklesaht, and Ucluelet people. New Journey Productions worked with the…

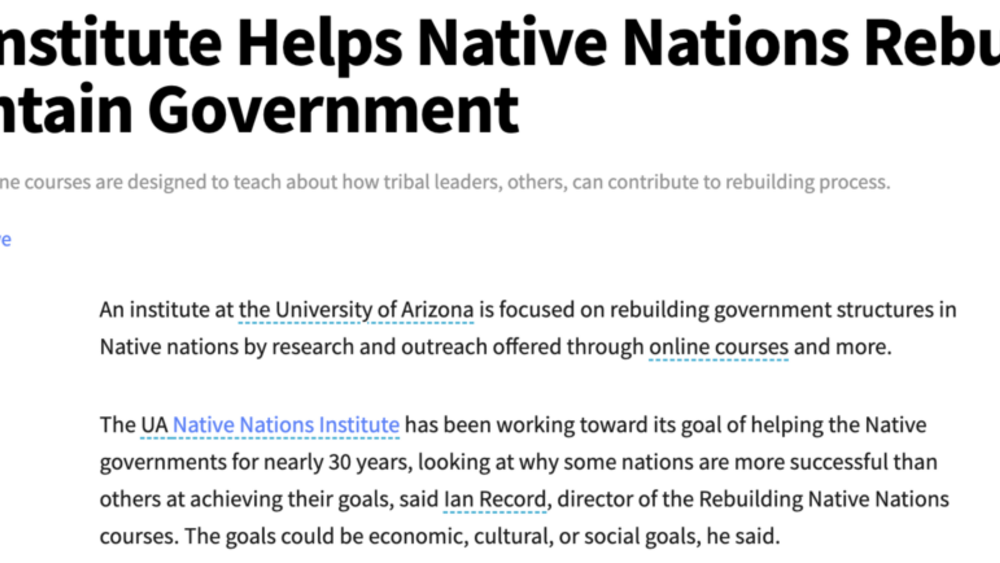

UA Institute Helps Native Nations Rebuild, Maintain Government

An institute at the University of Arizona is focused on rebuilding government structures in Native nations by research and outreach offered through online courses and more. The UA Native Nations Institute has been working toward its goal of helping the Native governments for nearly 30 years,…

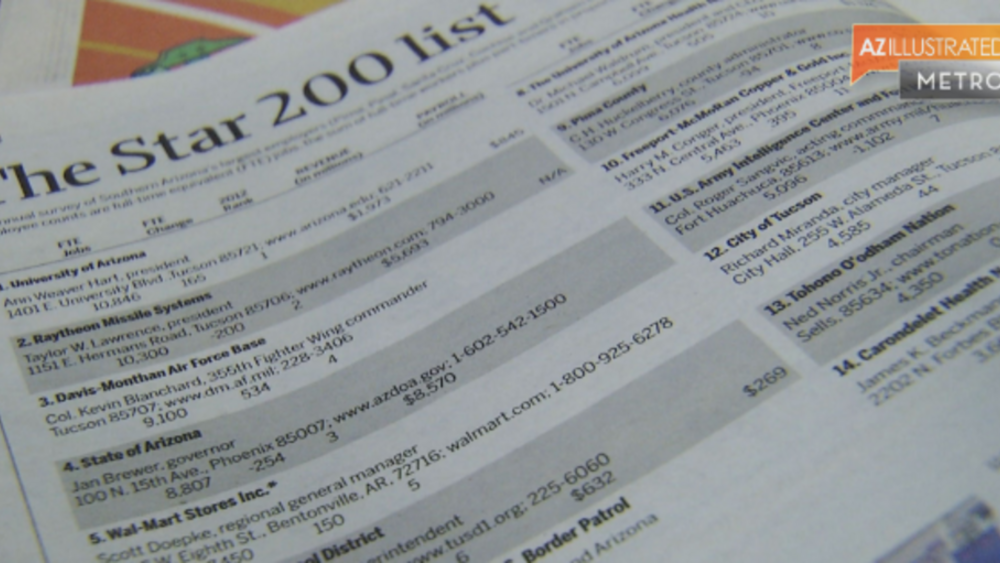

Arizona Illustrated: The Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series

Course series director Ian Record and course faculty member Robert A. Williams, Jr. appear on Arizona Public Media's "Arizona Illustrated" evening news television program to discuss the Native Nations Institute's groundbreaking "Rebuilding Native Nations: Strategies for Governance and Development"…

Native Report: Bush Foundation: Native Nation Rebuilders

On this edition of Native Report learn about the Bush Foundation's investment in sustaining the vitality of 23 Native communities across Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota. (Segment placement: 18:42-25:32)

Chief Oren Lyons Discusses Sovereignty

This is a short interview with Chief Oren Lyons on the issue of sovereignty that was filmed shortly after the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was passed.

Processes of Native Nationhood: The Indigenous Politics of Self-Government

Over the last three decades, Indigenous peoples in the CANZUS countries (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States) have been reclaiming self-government as an Indigenous right and practice. In the process, they have been asserting various forms of Indigenous nationhood. This article…

The Integration of Customary Law into the Australian Legal System

The theme of my address this morning emphasizes the important role that Indigenous people have, to take charge of our own destinies. The maintenance and integration of Aboriginal customary law is an essential part of this. It cannot be repeated often enough that a legal system must reflect the…

Indigenous Peoples’ Good Governance, Human Rights and Self-Determination in the Second Decade of the New Millennium – A Māori Perspective

This brief paper addresses the nexus between good governance, human rights and Indigenous peoples’ self-determination particularly from Articles 3-6 and 46 of the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The paper is placed within a Māori good governance context with some…

On Improving Tribal-Corporate Relations In The Mining Sector: A White Paper on Strategies for Both Sides of the Table

Mining everywhere is inherently controversial. By its very nature, it poses hard economic, environmental, and social tradeoffs. Depending on the nature of the resource and its location, to greater or lesser degrees, the mining process necessarily disturbs environments, alters landscapes, and…

Valuing Tradition: Governance, Cultural Match, and the BC Treaty Process

Self-governance negotiations are an integral part of British Columbia's modern day treaty process. At some treaty tables, impasses have resulted from differences on how to include traditional First Nations governance within treaty. Although some First Nations are determined to pursue traditional…

In Defense of Tribal Sovereign Immunity: A Pragmatic Look at the Doctrine as a Tool for Strengthening Tribal Courts

Although the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity was recently upheld by the Supreme Court in Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, its existence continues to be attacked as antiquated and leading to unfair results. While most defenses of tribal sovereign immunity focus on how the doctrine is a…

Managing Land, Governing for the Future: Finding the Path Forward for Membertou

This in-depth, interview-based study was commissioned by Membertou Chief and Council and the Membertou Governance Committee, and funded by the Atlantic Aboriginal Economic Development Integrated Research Program to investigate methods by which Membertou First Nation can further increase its…

Constitutions Fact Sheet

The National Centre for First Nations Governance developed this quick reference for Native nations who are discussing constitutions and constitutional reform.

First Nations Economic Development: The Meadow Lake Tribal Council

A new approach to economic development is emerging among the First Nations in Canada. This approach emphasizes the creation of profitable businesses competing in the global economy. These businesses are expected to help First Nations achieve their broader objectives that include: (i) greater…

The Last Stand: the Quinault Indian Nation's Path to Sovereignty and the Case of Tribal Forestry

This case tells a story of forestry management policies on the Quinault Reservation. In the early years, the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) and later the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) acted like a landlord, allocating large timber sales to non-Indian timber companies. The Dawes Act fragmented the…

The Will of the People: Citizenship in the Osage Nation

This teaching case tells the story of Tony, one of nine Osage government reform commissioners placed in charge of determining the "will of the people" in reforming the government of the Osage Nation. Because of Congressional law the Osage Nation had been forced into an alien form of government for…

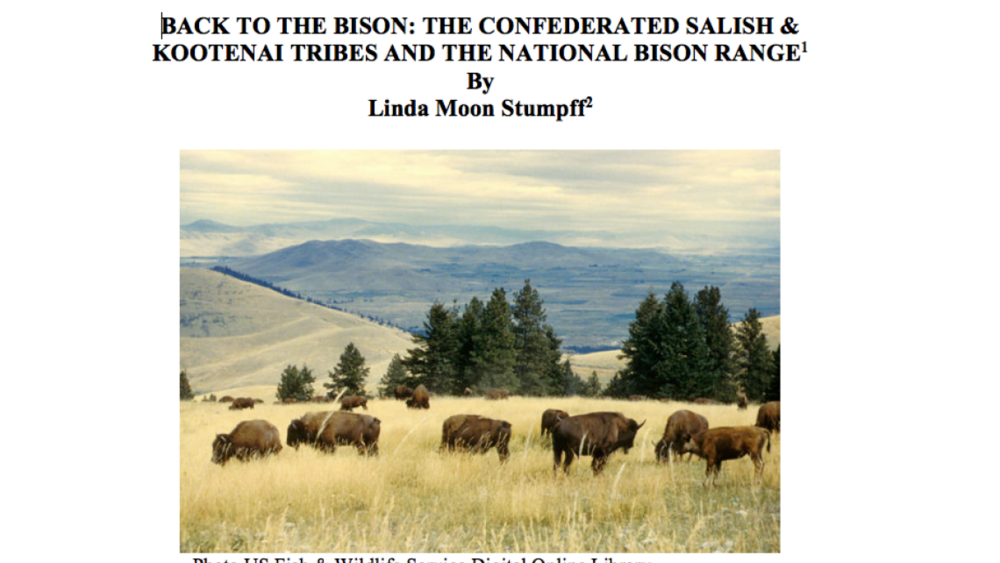

Back to the Bison Case Study Part I

Thirty years after taking over the reins of forestry, recreation, wildlife and other natural resource operations on their reservation lands, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) established a reputation for environmental leadership in wildlife, wilderness, recreation and co-management…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 3

- 4

- 5

- …

- Last page