Indigenous Governance Database

tribal courts

Pascua Yaqui gain added power to prosecute some non-Indians

Southern Arizona’s Pascua Yaqui Tribe is one of the first Native nations in the country to earn legal standing to prosecute outsiders who attack women on tribal lands. The Pascua Yaquis – along with the Tulalip Tribes of Washington and the Umatilla Tribes of Oregon – have been been awarded special…

Health, Innovation and the Promise of VAWA 2013 in Indian Country

Yesterday morning, we made our way north from Seattle, past gorgeous waterways, and lush greenery to visit with the Tulalip Tribes of western Washington, where we were greeted by Tribal Chairman Mel Sheldon, Vice Chairwoman Deb Parker, and Chief Judge Theresa Pouley. We saw first-hand, a tribal…

Hopi Revises Criminal Code, Regains Sovereignty

Crime rates in Indian Country are more than twice the national average. But for decades antiquated criminal codes have limited what tribal courts could do. For example, crimes like child abuse and sexual assault didn’t exist on the books. And, tribal judges couldn’t sentence a defendant to more…

Where Tribal Justice Works

In 2011, a man in northeastern Oregon beat his girlfriend with a gun, using it like a club to strike her in front of their children. Both were members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The federal government, which has jurisdiction over major crimes in Indian Country,…

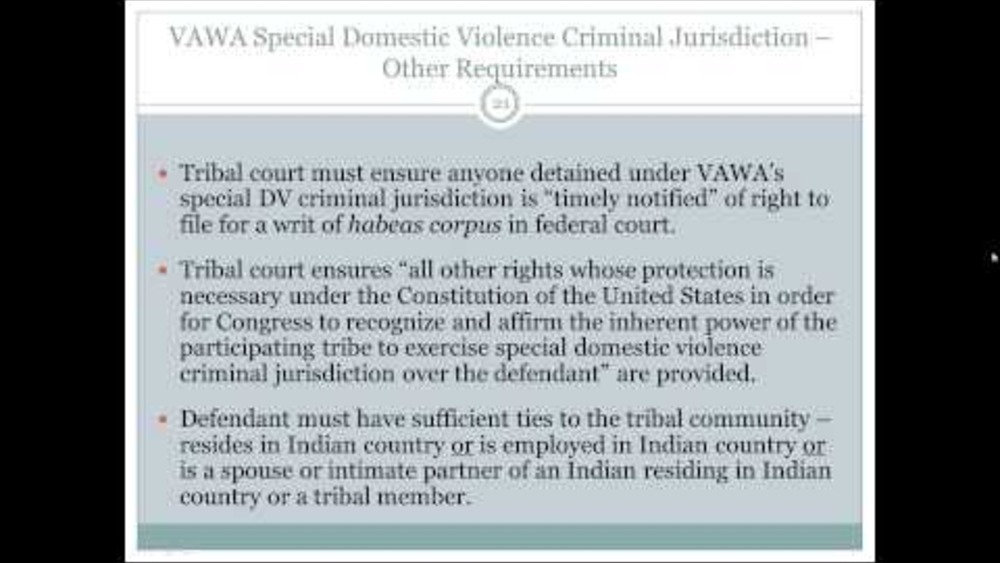

Navigating VAWA's New Tribal Court Jurisdictional Provision

President Obama signed into law the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), a federal statute that addresses domestic violence and other crimes against women. As initially conceived in 1994, VAWA created new federal crimes and sanctions to fill in gaps, provided training for…

Tribal Sovereignty Special

What does tribal sovereignty mean in Alaska? KNBA's Joaqlin Estus talks with two experts about the legal basis for tribal sovereignty, and tribal judicial systems at work in Alaska. Hear about a court ruling that Alaska tribes can put land into trust status, tax-free and safe from seizure...

Implementing VAWA's Expanded Jurisdiction in Our Tribal Courts

In coordination with the Tribal Law and Policy Institute, NCAI hosting this webinar on April 5, 2013. In this webinar, panelists discussed the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) provisions that expands tribal court jurisdiction over all persons for certain crimes committed on the reservation.

UA Institute Helps Native Nations Rebuild, Maintain Government

An institute at the University of Arizona is focused on rebuilding government structures in Native nations by research and outreach offered through online courses and more. The UA Native Nations Institute has been working toward its goal of helping the Native governments for nearly 30 years,…

A Way Out of Conflict

"A Way Out of Conflict" is a short documentary film that provides an overview of how traditional dispute resolution approaches and strategies operate in Hopi communities today. It examines how the Hopi villages retain and exercise authority over the adjudication of certain types of disputes…

Culture and Law: Preliminary Findings in a Review of 100+ Tribal Welfare Codes

Over the last 35 years numerous tribes have created their own child welfare standards. By crafting child welfare codes that balance traditional culture and contemporary needs, tribes both protect member children (and their families) in culturally appropriate ways and reaffirm their sovereign…

Resource Center for Implementing Tribal Provisions of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): Webinars

The Intertribal Technical-Assistance Working Group on Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction (ITWG) has participated in a series of webinars focused on defendants' rights issues (including indigent counsel); the fair cross section requirement and jury pool selection; prosecution skills;…

In Defense of Tribal Sovereign Immunity: A Pragmatic Look at the Doctrine as a Tool for Strengthening Tribal Courts

Although the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity was recently upheld by the Supreme Court in Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, its existence continues to be attacked as antiquated and leading to unfair results. While most defenses of tribal sovereign immunity focus on how the doctrine is a…

Considerations in Implementing VAWA's Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction and TLOA's Enhanced Sentencing Authority: A Look at the Experience of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe

On February 20, 2014, pursuant to the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (VAWA 2013), the Pascua Yaqui Tribe was one of only three Tribes across the United States to begin exercising Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction (SDVCJ) over non-Indian perpetrators of domestic…

Negotiating Jurisprudence in Tribal Court and the Emergence of a Tribal State: The Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe

The interaction between American Indian activism and changes in federal Indian policy since the 1960s has transformed American Indian tribes from largely powerless and impoverished kinshipâ€based communities into neocolonial statelike entities (Wilkinson 2005).1 Representing themselves as distinct…

![Tribal Law as Indigenous Social Reality and Separate Consciousness: [Re]Incorporating Customs and Traditions into Tribal Law Tribal Law as Indigenous Social Reality and Separate Consciousness: [Re]Incorporating Customs and Traditions into Tribal Law](/sites/default/files/styles/resources/public/resources/Screen%2520Shot%25202016-10-11%2520at%25201.22.13%2520PM.png?itok=pvkjKhR1)

Tribal Law as Indigenous Social Reality and Separate Consciousness: [Re]Incorporating Customs and Traditions into Tribal Law

At some point in my legal career, I recall becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the inconsistencies between the values in the written law of various indigenous nations and the values I knew were embedded in indigenous societies themselves. The two are not entirely in harmony, and in fact, in…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- …