Indigenous Governance Database

Yup'ik

Thumbnail

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: Mike Williams

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-…

Image

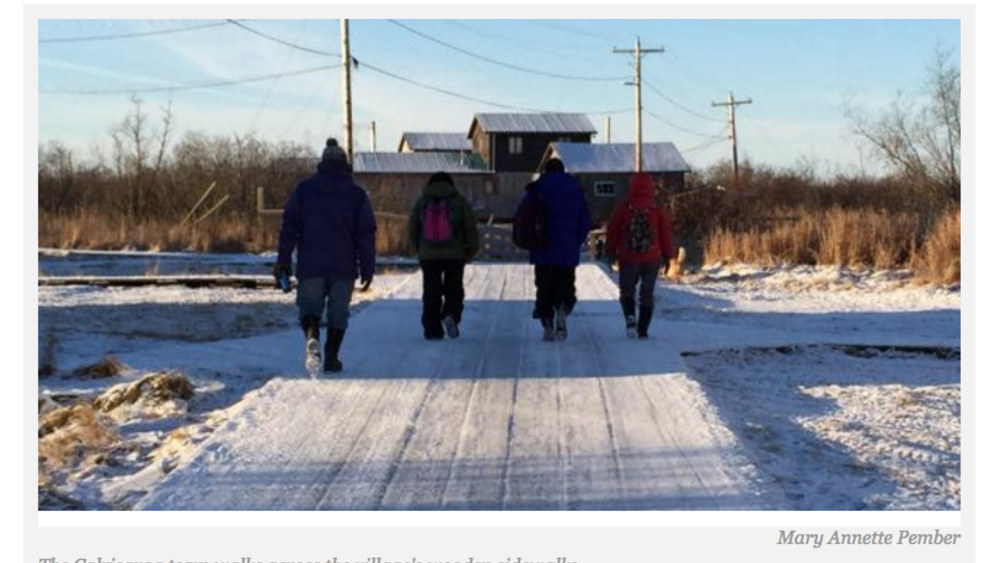

A Fearless Fight Against Historical Trauma, the Yup'ik Way

They were building the young man’s coffin in the front yard when we arrived. Portable construction lights harshly illuminated the scene as men worked in the shadowy dawn that lasts almost until noon out here on the tundra. The men worked steadily and quietly in a manner that suggested front-yard…