Indigenous Governance Database

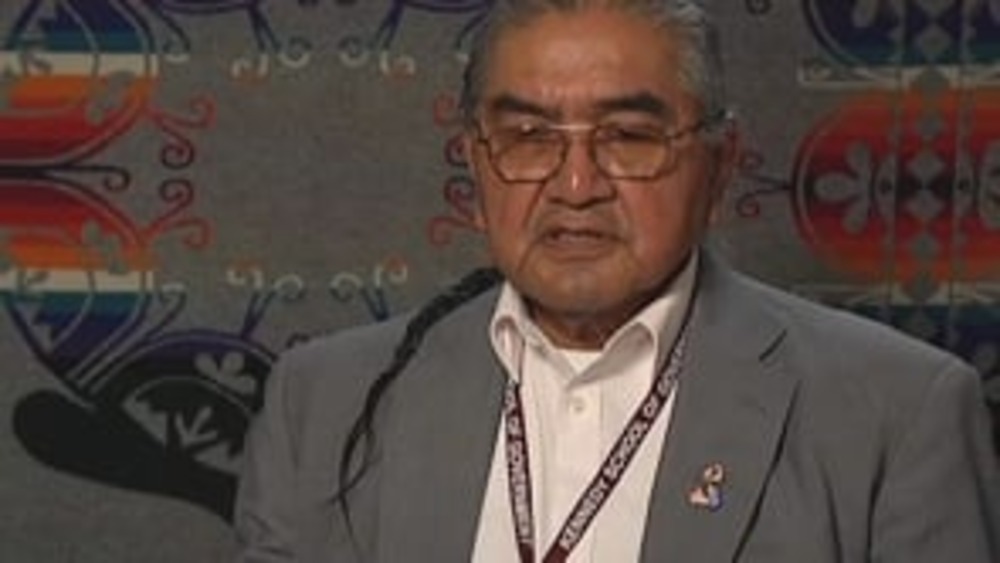

Denny Hurtado

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "The Importance of Strategic Planning"

Native leaders explain the importance of strategic thinking and planning to effective Native nation governance and emphasize the consideration of future generations in Native nations' decision-making processes.

Denny Hurtado: Addressing Tough Governance Issues

Former Skokomish Tribal Nation Chairman Denny Hurtado discusses how he, his fellow leaders and his nation exercised its sovereignty in order to navigate past some tough governance challenges to fund their government, restore their land base, and protect their natural resources.

Charles E. Odegaard Award 2014: Denny Hurtado

Denny Hurtado, former chair of the Skokomish Tribe and retired director of Indian Education for the Washington State Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, is the 2014 recipient of the University of Washington Charles E. Odegaard Award. This honor is regarded as the highest achievement…