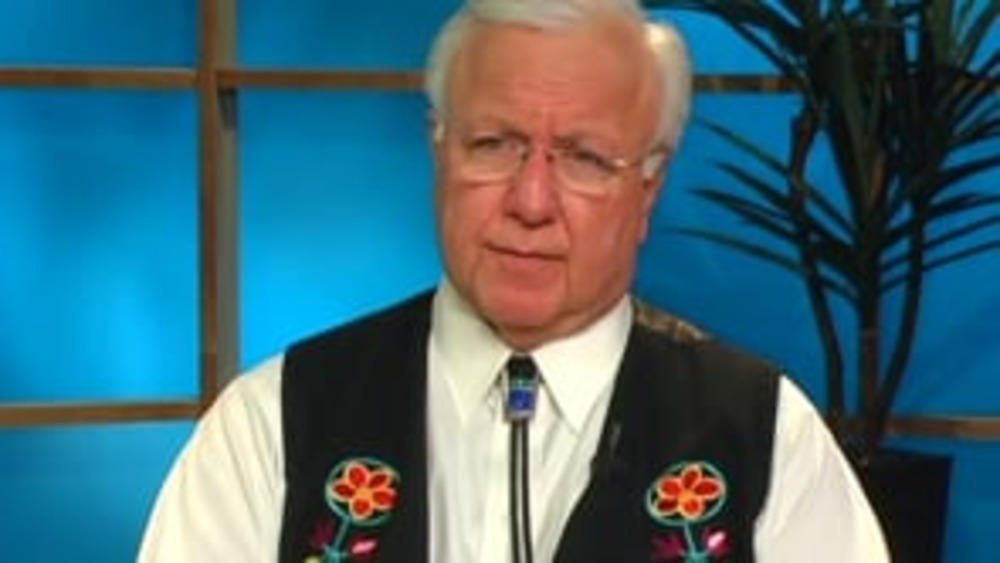

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman John "Rocky" Barrett shares the history of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and discusses its 40-year effort to strengthen its governance system in order to achieve its goals.

Additional Information

Barrett, John "Rocky." "A Sovereignty 'Audit': A History of Citizen Potawatomi Nation Governance." Emerging Leaders seminar. Native Nations Institute for Leadership, Management, and Policy, University of Arizona. Tucson, Arizona. October 11, 2012. Presentation.

Transcript

"[Potawatomi language]. It's nice to see all of you emerging tribal leaders. That's wonderful. I like to think of myself as emerging, hopefully on a constant basis. I was first elected to office in 1971 as a 26-year-old whatever I was at the time. I was selected as vice chairman. I was named to finish a term and then I was...the two year terms back then. Then I was elected about seven months later for a two-year term as vice chairman. Vice chairman of what was hard to say at that time. My uncle was the chairman. My mother and her eight brothers and sisters were agency kids. We grew up...they grew up on the BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] Agency. My grandfather was the BIA marshal then or the tribal...or the BIA police. And so that area...I am one of the eighth generation of my family consecutively to be chairman of the tribe. Back in those days when that vacancy came up, it came up because my uncle had been named chairman because...he was the vice chairman and the chairman had gotten removed from office for carrying around the tribal checkbook in his hip pocket and writing checks to the grocery store for groceries. And we only $550 in the bank and he used about $100 of it to pay his grocery bill and the feds got him. So he was removed from office and my uncle was made chairman, which created a vacancy in the vice chairman spot and so I was named to it.

And we went over to the BIA Superintendent's office. Now you've got to understand my uncle grew up on the Agency and the BIA in 1971 was the law. And he didn't believe you could have an official meeting of the tribal government without the Agency superintendent in the room and that the minutes of our meetings were not official unless they were filed with the BIA. So we went over to see the Agency superintendent and he was going to tell the superintendent that we were going...the tribe was going to appoint me as vice chairman. Now why, I don't know. But we go in and the Agency superintendent starts trying to talk him out of it and he finishes up by saying, ‘Now the last thing I want to do is hurt you guys.' And so as we're going out the door, my uncle turns to me and says, ‘That means it's still on the list,' to hurt us.

So I got the drift about then and, but...became the vice chairman and served two terms then I became director of the inter-tribal group. The State of Oklahoma forced all of the tribes -- the federal government forced all the tribes in the ‘70s to create inter-tribal corporations that were chartered C corporations or non-profit corporations in the State of Oklahoma. The federal government would not give money to an Indian tribe back in the start of the old [President] Lyndon Johnson program days. So you had to be given to a corporate entity that was in the state. And the state even tried to take 10 percent off the top of every federal dollar that came to Oklahoma as a condition. The issue back then was whether or not tribes were responsible enough to manage the money and everyone...I was the youngest person on the business committee. I was the only high school graduate; I was one of the three out of five who could read. All of the people on the business committee were smart but they were not educated people, but they had all grown up...of course, I'm not smart enough to know how to operate this damn thing. There we go. I did a good job of that, didn't I? Side to side or up and down? Ah, okay, that was the problem I went... I killed it. No? Ah.

But the Citizen Potawatomi Nation back then was the Citizen Band of Potawatomi Indians of Oklahoma, was the name of our tribe. The 'Band' was something the BIA stuck on us in 1867, actually 1861 when we separated from the Prairie Band when we were all one tribe. We tried to get Band out of our name for almost 75-80 years after that and finally were successful. We still can't get the BIA to stop calling us that even 20 years later. But we're the Citizen Potawatomi Nation; implication being that 'Band' is not a full-blown tribe.

But what's described as this audit of sovereignty -- we weren't that smart. We didn't just all of a sudden one day decide, ‘Oh, we're going to audit our sovereignty. Where are we sovereign? And where are we not sovereign? And here's what we're going to do about it.' We weren't that smart. We really didn't know what sovereignty meant. Remember, everyone on the committee, and this includes me, we were all children of the ‘50s and the ‘60s. Primarily, except me, were children of the ‘40s and ‘50s. You've got to remember what was going on about then. 1959, Senator Arthur Vivian Watkins of Utah chaired the Interior Committee of the Senate...Interior Committee on Indian Affairs and helped shepherd through House and Senate Concurrent Resolution 108 was provided for termination of tribes. The Secretary of Agriculture, who was also from Utah at the time, in the interest of doing something good for Indians, were tremendous proponents of termination and got it done. The McCarthy hearings were on about then and anybody who held things in communal ownership was probably a communist and that included Indian tribes. Yeah. And if you were an Indian leader and you didn't like the way the federal government treated you, it wasn't that you were saying that you didn't love the government, it's when you discovered that your government didn't love you is when all of a sudden things got rough.

And this was a tough period of time and everyone on the business committee, all five of us, were all a product of when self-governance and self-determination, that was the language of termination. Self-determination and self-governance meant termination. That's what they said they were going to do. And in those days you had to prove that you were going to be too broke and too incompetent to run your own affairs to keep from being terminated. If you had a business and you had money and you were conducting your affairs in some semblance of order, then you were eligible for termination and we were on the list. Why? I don't know because we had neither pot nor window. And it was...it was absurd that all the Potawatomis got thrown in there together 'cause we were down to $550 in the bank and two-and-a-half acres of land held in common, in trust, and about 6,000 in individual allotments. We were down to nothing and they were going to terminate us. And my uncle, listening to the Choctaw chief at that time who -- remember, the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek, Seminole chiefs were appointed by the president until some 20 years after that. They were not elected. So the Choctaw chief was a big proponent of termination. He believed that was the right thing to do. My uncle didn't think that we should be terminated but didn't even really know what we were being terminated from 'cause we didn't own the building where we met. It was a trailer that the [Army] Corp of Engineers had abandoned on a piece of land that the BIA had and they were letting us use it. We were pathetic, pitiful people.

And so when they started these hearings on Indian stuff and the outcome of it was Senate Resolution 108 and the Flathead, Klamath, Menominee, Potawatomi, Turtle Mountain Chippewa and all the tribes in the State of California, New York, Florida and Texas were to be terminated. Now 108 didn't terminate them, but it authorized the termination and then the BIA started working up the list. When I said earlier that the BIA superintendent said, ‘The last thing in the world we want to do is hurt you, but it's still on the list.' So, that was the mindset of our business committee and when I took office of our tribal government. Senator Watkins had the support of Senator Robert S. Kerr, the owner of Kerr-McGee Oil Company, to date the richest man who's ever served in the United States Senate and was the most powerful man in the U.S. Senate and coined the phrase what we call a Kerrism and that's still in use in Oklahoma is that, ‘If I ain't in on it, I'm ‘agin it.' And that's how he got in the uranium business. All that saved us was we sued the government in 1948 under the Indian Claims Commission Act and that lawsuit settlement was pending and tied up in the courts and if it hadn't been for that they would have terminated us 'cause you can't terminate someone who's in court suing the government cause it looks like you're trying to get rid of them to get rid of the lawsuit and that's all that saved us.

Very quickly, we came from Newfoundland down the Saint Lawrence River 1100, 1200 mini-Ice Age, ended up in Michigan, split from the other...the Ojibwa, Odawa, Ottawa people. We were all one tribe called Anishinaabe, we came into Michigan and settled. In the war with the Iroquois over the beaver trade they drove us all the way around the lake until the French armed us and then we drove them back to the east coast. We were in refuge in Wisconsin from the Iroquois attacks when the French, John Nicolet showed up with some priests and we helped unify the Tribes of Wisconsin against the Iroquois invasion and that group was able to drive them back once armed with the French connection. The French connection through a series of alliances, primarily inter-marriages and the inter-married French and Potawatomi became the Mission Potawatomi who became the Citizen Potawatomi.

But this area was an area that we controlled quite a large area, though it didn't show up on the slide, but it was a very large area around the bottom of Lake Michigan and then because we sided with the French against the British, with the British against the colonies, we ended up under the Indian Termination or the Indian Relocation rather, Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act and we got marched to the Osage River Reservation in a march of death along this route and the ones that didn't die on the walk, another fourth of them died that winter. My family survived it on both sides and in 1861 after the Copperhead [U.S.] President Franklin Pierce allowed settlers to come into Kansas on top of the reservations anyway without a treaty. We were on the Kansas/Missouri border. We were part of the Underground Railroad to help hide runaway slaves and transport them up north. And so we were part of the depredations of the Civil War from Missouri, a slave state, into Kansas.

And so we ended up getting out of there, separated from the Prairie Potawatomi in 1861, sold the reservation to the Atchison-Topeka and the Santa Fe Railroad in 1867, took the cash and bought this reservation for gold south of the Canadian River from the Seminole Reservation line to what's called the Indian Meridian that divides the state in half between the North and South Canadian rivers, became our reservation that we purchased. And we took United States citizenship as a body in 1867 in order to protect the ownership of that property as a deed. We were denied access to the courts in removal from Indiana. We had lawyers hired and people trying to stop the removal from Indiana and we were part of the group that was...the ruling was that because we were not United States citizens we could not plead our case in the United States courts. And hence the name Citizen Potawatomi was to defend the purchase of this property.

We came to a place called Sacred Heart. We had the Catholic Church with us and helped them form the first Catholic university and school, settled in Sacred Heart. We had a division over the Ku Klux Klan. We had a Protestant and Catholic business committee. Of course the Klan was as strong in Oklahoma and Indiana as it was in Mississippi and Alabama and it caused a great deal of trouble. The Shawnee Agency government in Shawnee where the Indian Agency was basically after the tribe was able to heal the split, we didn't have a headquarters after we left Sacred Heart. The trailer that you see on the bottom was a...belonged to the Corp of Engineers and it set on a surplus piece of property. I want to get a little larger version of that picture because it's so much fun. Car and Driver Magazine certified the three worst cars in U.S. history were the Ford Pinto, the AMC Gremlin and the Opel Cadet, and all three of them are parked right there. First thing we did was out of the 550 bucks, we spent $100 of it on that air conditioner 'cause it was too hot to sit in this trailer. The guy who got removed for writing those checks got drunk with his brothers and came to whoop us all at the first meeting and the chairman...I mean the guy who was supposed to succeed, because I got appointed he showed up, is how I got appointed. But he showed up to become the first choice appointee and he kicked a hole in the back of it right here 'cause this was the only door to get away from the impending fist fight. But it was mostly conversation, nothing happened. But that was us in '73 on a gravel road. That was all we had.

In 1982, I had left the inter-tribal group and left tribal office and gone back to the oil field and in 1982 my grandmother whose father and grandfather and great grandfather and great-great grandfather had been chairman and my mother's father and my grandfather also on his side had been and my grandmother called me up and told me that I needed to come back and I said, ‘I've already done my piece, grandma. You've got 26 other first cousins. Why don't you get them to do it?' And I got that silent thing and she scared me to death with that so I went back out there in '82, in 1982 because I'd had the previous history in office and as running the inter-tribal group. Became the tribal administrator in '82. I served until I ran for chairman in 1985.

But in 1984 there was a set of tribal statutes that were being promulgated by a now famous Indian lawyer named Browning Pipestem, the late Browning Pipestem. Browning Pipestem and William Rice, Bill Rice, made a presentation to us. Now I was the tribal administrator. The chairman at the time had a reading disorder so the way that business went of our tribe was he would go out in the hall and his wife would read it to him and he would come back in and reconvene the meeting and we would handle that piece of business. This meeting started about 5:30. It was about 1:00 am when Browning Pipestem and William Rice finally got the opportunity to speak. Browning Pipestem was married to a Citizen Potawatomi. He was Otoe Missouri and he started the meeting off, 'cause he'd been cooling his heals out in the hallway for about five or six hours, by saying, ‘I own more land than the Potawatomi tribe. I have more trust land than you do. My children have more trust land than you do. The area over which you govern, my family owns more than you do.' Well, it was kind of an odd thing to say, but I knew Browning was...he was a riveting speaker, and I knew he was going somewhere with this and he said, ‘You guys are known up north as the shee shee Bannock,' the duck people, because we were so good with canoes. Supposedly Potawatomis invented steam bending the keel of a canoe to avoid knocking a hole in the bough on rocks on rivers. ‘You guys are called the duck people by the other tribes 'cause you got around in so much active in trade and so much commerce and you got around so well on the water.' And he said, ‘Well, here's what sovereignty is. If it walks like a duck and it talks like a duck, it's a duck most likely, and sovereignty is the exercise of sovereignty. It's not something that you get, something that you buy or something that someone gives you. It's like your skin. You had it, you are a sovereign, the United States signed treaties with you, 43 of them, all of them broken, the most of any tribe in the United States, the most treaties of any tribe. And they don't sign treaties with individuals and they don't sign treaties with oil field roughnecks. They sign treaties with other governments. You are a sovereign government with the United States and sovereign means the divine right of kings.' Well, he lost us there and he went on to say that...explaining that ‘unless you take on the vestiges of a sovereign government and exercise the authorities of a sovereign and recognize where you can exercise your sovereignty and where you cannot and what it is, then you're not. But if you do, you are.'

Well, for me the lights went on about then because the Thomas-Rogers Act constitutions in the State of Oklahoma, all the tribes in Oklahoma adopted the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act Constitution and it basically...that was back in the days when it was the fad, we all had to be corporations. I'm the chairman of the tribe and we have a vice chairman and a secretary/treasurer and we have members of the business committee, like a board of directors of a corporation. And somehow they thought that our way...best way to govern is that we would all get together in this thing called the general council that would be the supreme governing body of the tribe and that we all got together and everyone had an equal voice, the 18-year-old had an equal voice with the 65-year-old and everyone would get together and democratically design the best thing for the tribe, which is utter nonsense. Absolutely utter nonsense. We never governed that way in our history. If you got up in my day as a young person and had something to say in council, your grandpa would and could and should grab hold of your pants and jerk you back down and apologize for the fact that you spoke at all without asking the permission of your elders.

Of course our government, because it was a meeting...now we didn't have anything, we were broke. We didn't have any land, didn't have money, we didn't have anything but we could meet in the one general council that we had annually on the hottest day of the year and the last Saturday in June at our annual general council that convened about 1:00 and we'd keep going ‘til about 7:00 when the low blood sugar kicked in and it would come to blows. And as a result of that, we couldn't get a 50-person quorum. We had an 11,000-member tribe. We couldn't get 50 people to come to council. We used to have to get in our cars and delay the start of the meeting to go around and force your cousins to get in the car so we could get a quorum so we could convene the general council meeting. No one wanted to come and I don't blame them. I didn't want to go either. If I hadn't been in office, I wouldn't have gone. It wasn't government. It turned into a bad family reunion. That's all it turned into. And so the...what happened out of that, calling that government, was the more acrimonious the meeting became, the less people wanted to come, and the less like government it was. And it wasn't a government. We weren't governing, we weren't sovereign, we weren't anything.

So first thing that came to us is, ‘We've got to change this Thomas-Rogers Act thing.' The supreme governing body of the tribe can't be a meeting, and we could call special meetings of general council with a petition and 25 people could call a petition and you could get another meeting and get 50 people there and 26 of them could change everything that the previous one did. So one family could all get together and we could back and forth have these special general councils and we could reverse this and change this and chaos, utter chaos. So we decided to redefine what the general council was, if that was to be the supreme governing body of the tribe, it had to be the electorate, it had to be the people who were eligible to vote, the adults of the tribe. And so that was the first thing we decided to do, but that evening it ended about 2:00 and we all went home.

But the next few days we started talking about, ‘What does a tribal government do? What are we supposed to be doing here? We're getting a few bucks from the government here and there to try to keep the lights on.' We had $75 a month coming in of revenue and it kept the lights on but, ‘What are we?' So we got it down to three things: the land, the law and citizenship. What land do we govern? What's a law? So it was about three years and I got elected chairman in 1985. I came back in '82, I ran for chairman in '85 and have been in office since then. We've amended our constitution five times since then. One really major one and we have been to the United States Supreme Court three times, to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals seven times. We have been in litigation every year since 1985. We're still in litigation. I'm a lawyer's dream -- not one penny in tribute and millions for defense. That's not my saying.

When we talk about the land, how much land do we govern? Now we had that two-and-a-half acres of land that was held in common, we had about 60 acres that was in fee that was old school land and then we had about 6,000 acres of land that was held in trust that had a whole variety of heirs, very few people living on it. And you could fly over the countryside of Oklahoma on our reservation and here'd be a whole bunch of land that was all in cultivation, people making hay and raising cattle and then there's be an 80-acre piece right in the middle of it that was overgrown with blackjack trees and weeds and trash and no fences and crummy looking un-utilized piece of property and that was a Potawatomi allotment. That's how you could tell because with so many heirs no one actually owned it, no one actually used it. It was in the fourth generation of ownership of a family that was split up to where it wasn't happening. Plus the fact the government at that time, there was a big move that tribes that were allotted tribes that didn't live on Indian Reorganization Act reservations like most of you guys weren't really tribes and really didn't have a definable jurisdiction. That was before the federal definition of Indian Country.

How much land do we govern, what are our boundaries, what authority do we have over our land, can we buy more and will it become subject to the authority of our government and what's the difference between allotted land and tribal trust land? We didn't know that. We didn't know. We didn't know that allotted land was subject to the authority of the tribal government even though the only thing we had were resolutions. We didn't have statutes, we didn't have a code, we didn't have a court, we didn't have police, we didn't have the vestiges of the government, but we had resolutions. That's how we decided what to do and we could do a resolution that would have an impact on tribal trust land if you could survive the political outfall. We didn't know that. We didn't know that our boundaries where we could take land and buy the residual interests in the allotted lands was the original jurisdictional boundary of the reservation, the 900 million acres that we lost. What authority did we have over the land? We didn't know we had authority over anything. Remember, we thought we had to have permission from the Agency to meet. So it was the discovery and the inquiries that we began about what our land base was, what our boundaries were, where could we buy land and get it put into trust; we were told by the Agency superintendent that no individual could put land into trust. And the reason was that you had to be incompetent for them to put individual land into trust. And if you were smart enough to ask to get your land put into trust, you weren't incompetent. Catch 22.

The law. We didn't know we could pass a law. We were passing resolutions; we didn't know they were laws. We have a resolution, ‘We're going to meet next Friday and have a pie supper.' We didn't know that was the law. We didn't know a tribal resolution was law. When we enrolled someone, we didn't know we were behaving lawfully. We knew we had to follow the constitution. We thought the constitution was the only law we had and if it wasn't in there it didn't exist. If it wasn't in the book, in the constitution book, it didn't exist. How we enforced law. We didn't have police. The BIA had police but we didn't have police. We didn't know you could have police. We didn't have a judge for sure. The CFR courts hadn't even been invented.

In CFR, the Court of Federal Regulations, that didn't really start happening until about 1981, '80, in Oklahoma. Can we make white people obey our laws? Can white people come onto our land and shoot game? Can white people lay a pipeline right across our land and not tell us or get permission? Can they run cattle on these allotments which they were doing. Can they produce oil off of those allotments and not pay us? All of those things, we didn't know how to do that. Does the BIA, whose law...do we have any impact on the BIA, do they have to do what we say? Does the State of Oklahoma? And if we have laws is there a Bill of Rights? Can we pass a law that says that my political opponent needs to be put in jail for being a fool and is there an appeal? And worse yet, the big scary one, the word, the 800-pound gorilla in the room, the one word nobody wanted to use was can we levy taxes? Whoo hoo hoo. Taxes.

Citizenship. We knew we could amend our constitution because they told us that the only way we were going to get this payment from the 1948 Indian Claims Commission, the 80 percent of the settlement that had been tied up since 1948, in 1969 is we had to have a tribal roll and the BIA told us that the only way you could be on the tribal roll was to prove that you were 1/8th or more Citizen Potawatomi. Now the blood degrees of the Citizen Potawatomi were derivatives of one guy from the government in a log cabin in Sugar Creek, Kansas in 1861 who was told to do a census of the Potawatomi, the Prairie Potawatomi and the Citizen Potawatomi. And he told everyone that they had to appear. And as they came in the door, he assigned a blood degree based on what color their skin was in his opinion and full brothers and sisters got different blood degrees, children got more blood degree than their parents 'cause they'd been outside that summer and those were the blood degrees of the Citizen Potawatomi. There was a full-time, five-person staff at the central office of the BIA in Washington, DC, who did nothing more than Citizen Potawatomi blood-degree appeals, about 3,000 of the blood-degree appeals when I first took office. When I became chairman, it had grown to 4,000 or 5,000 and I was in the room when a guy named Joe Delaware said, ‘I have a solution to the Potawatomi blood degree problem. We'll resolve all this. The first mention in any document, church, federal government, anywhere, anyhow that mentions this Indian with a non-Potawatomi language name, he's a half.' Well, they were dunking Potawatomis and giving them Christian names in 1702, full-blooded ones. If you were dealing with the white man, you used your white name and if you were dealing with the Indians you used your Indian name, like everybody else was doing. And so it was an absurd solution. I told him, I said, ‘That's nuts. That's just crazy. You're going to get another 5,000 blood-degree appeals over this.' He said, ‘Well, that's the way it's going to be.' Well, that was the impetus for our coming back and establishing, ‘What are the conditions of citizenship?' And we stopped called our folks members like a club. They're citizens. And it finally dawned on us that being a Citizen Potawatomi Indian is not racial. It's legal and political. If they...according to the United States government, if a federally recognized Indian tribe issues you a certificate of citizenship based on rules they make, you are an American Indian, you are a member of that tribe. And you're not part one, not a leg or an ear or your nose but not the rest. You're not part Citizen Potawatomi, you're all Citizen Potawatomi. The business of blood degree was invented so that at some point that the government established tribes would breed themselves out of existence and the government wouldn't be obligated to honor their treaties anymore. That's the whole idea. That's the whole idea of blood degree and we're playing into it all over this country, now over divvying up the gaming money. But I'm not going to get into that. But the business of blood degree, the 10 largest tribes in the United States, nine of them enrolled by descendency and that includes us. We changed it from blood degree to descendency, which was the only reasonable way to do it because we had no way to tell because of this guy in the log cabin in Sugar Creek was what we had. And then we had permutations of that over the next eight generations that became even more absurd and Potawatomis had a propensity...we're only 40 families and all 31,000 of us had a tendency to marry each other. So when one Potawatomi would marry another Potawatomi, I'm not saying brothers and sisters or first cousins but when they'd marry another Potawatomi then you got into who was what and it was... And this business of the certified degree of Indian blood was ruled to be unlawful, to discriminate against American Indians in the provision of federal services based on CDIB. It's supposed to be based on tribal membership, not the BIA issuing you a certified degree of Indian blood card. A full-blooded Indian who is a member of eight different tribes, whose family comes from eight different tribes, not any white blood, would not be eligible to be enrolled in many tribes. They had absolutely no European blood, would not be eligible simply because he was enrolled in multiple tribes.

The other thing about citizenship is ‘where do we vote?' The only way you could vote in an election at Citizen Potawatomi was to show up at that stupid meeting, violent meeting, and the guys that were in office would say, ‘Okay, everybody that's for me stand up.' Well, nobody could count that was on the other side so everybody would kind of creep up a little bit so you could count. Well, they counted you 'cause you creeped up a little bit so you voted against yourself. So the incumbent would say, ‘Okay, everybody that's for this guy stand up. I won.' Well, that's not how to elect people. That's not right. Two-thirds of our population lives outside of Oklahoma, one-third of it lives in Oklahoma. Those people are as entitled to vote as anybody in the tribe, so the extension of the right to vote and how we vote and whom we vote [for] and what the qualifications of those people and the residency requirements of those, that was an issue of citizenship that we needed to determine.

So we went through a series of constitutional amendments. We redefined the general council as everyone in the tribe over 18, is the general council and that is the electorate, that's who decides all issues subject to referendum vote. Everyone in the tribe can vote by absentee ballot if they register to vote in an election. We established tribal courts that are independently elected just like the chairman and vice chairman and the members of the tribal legis...and secretary treasurer and the members of the tribal legislature and that the tribal courts have authority over all issues relating to law enforcement. We adopted a set of tribal statutes and we used the ability under the Indian Reorganization Act that we recede the authorities of the IRA in our new constitution to have a tribal corporation in addition to the tribal government, two separate entities. An incorporated entity and the sovereign entity is the Citizen Potawatomi Nation government. Next amendment was to change the name to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation from the Citizen Band Potawatomi. ‘Cause back then when you had Citizen Band, people would say, ‘What's your handle good buddy? 10-4. What's your 20?' Remember all that stuff that went on back in the day with the Citizen Band radios? Or what instrument do you play in the Citizen Band? That was the other one I used to get all the time. We changed our name and we went to descendency citizenship and we enrolled everyone that needed to be enrolled if they were descendents of the original families, 41 families that made up the tribe in 1861.

I issued an executive order that we would hold council meetings in every area, city or metropolitan area with more than 2,000 members of the tribe. And so we began a series of meetings in 1986 in Houston, Dallas, Washington, D.C., Kansas City or Topeka area, Kansas City/Topeka area, Portland, Oregon, alternating with the Seattle/Tacoma, northern California -- the prune-pricker Potawatomis. We met in Sacramento, in southern California -- the oil field Potawatomis. We met in Los Angeles or somewhere, Bakersfield or somewhere down there. And we met in Phoenix, Arizona, for the rich Potawatomis. But we started having these meetings and we started going to hotel rooms and ballrooms like this one and buying a meal ‘cause we had a little money coming in from bingo and selling cigarettes and we started having these meetings and we found out something, that if you have a meeting and you feed Potawatomis, they won't fight with you. So as soon as I started serving food at the general council back home, never another cross word, never had another fight, never any issues of that.

But the revision of 2007...in 1985 was the big one. I almost...I'm out of time. We separated the branches of government with a true separation. There is an executive branch, a legislative branch and a judicial branch. We now have 16 members of the tribal legislature, eight from Oklahoma and eight from outside of Oklahoma. While it's a one-third/two-thirds population, the way we balanced that is that of the eight from Oklahoma three, the chairman, vice chairman and secretary/treasurer, are elected by everyone in the whole United States. So there is a nod or an impetus or balance given to the population outside. The fact that our jurisdiction, that the area over which we govern, our revenue, is all based in Oklahoma on the reservation is recognized by the fact you have to be from Oklahoma to be chairman or vice chairman or secretary/treasurer. Legislative districts. The whole United States is represented. We eliminated the grievance committee. The grievance committee existed because we didn't have a tribal court and the grievance committee created grievances. We had staggered terms of four office...for four-year terms of office, staggered terms of office. The old two-year terms of office where we turned over the majority of the government every 24 months, crazy. The legislature has total appropriation control of the money. But the legislature can't even answer the phone. It speaks and acts by resolution and ordinance only. They can't run the government ‘cause they can't even answer the phone. The legislature speaks and acts by resolution or ordinance. They appropriate the monies for a specific purpose, but the executive branch spends it and runs the tribe. I have a veto, I have 10 votes out of 16 not counting mine so 10 votes out of 15. And the BIA no longer has to approve our constitutional changes. Each of our constitutional changes took the BIA over four years to consider.

So that's where we are, that's the old bingo hall, that's Firelight Grand Casino. It's $120 million operation, we're doing $150 million addition to it now. Everywhere in our tribe we have these symbols of corn plants. Don't eat the seed corn. We do not make per capita distributions. We fund 2,000 college scholarships a semester, we provide free prescriptions to everyone in the tribe over 62 wherever they live, we do home loans for people, we do all of those things based on need, not actual checks. We believe we're like a family. No one comes homes, sits down at the table, brings the kids and wife and sits there and says, ‘Okay, I'm going to divvy up the paycheck.' They don't do that. They pay the bills first, they address the needs of the family first, and then if there's discretionary income they decide whether to save it, invest it or spend it and that's the way we do ours. But we consider the money from gaming to be found money; it's seed corn.

We bought this bank on a gravel parking lot. It was a prefabricated structure and it was failing. We bought it from the FDIC, the first tribe in the United States to buy an operating national bank. It took the government six months to decide whether to let the bank fail and break all of the depositors or let us put a million dollars in it and save it. They finally decided to do that and now First National Bank is the largest tribally owned bank in the country. We have seven banks, seven branches and it's $250 million back from the original $14 million. If you're going into the bank business, be a little more financial healthy than we were ‘cause if the tribal chairman has to go repo boats and cars at night, that's an ugly business. That's no fun. We had a repo guy named One Punch Willie and boy, he was a tough...he could steal a car in 30 seconds and I went with Willie out...Willie Highshaw, went out on the lake with Willie Highshaw, a great guy. We went out and repoed cars at night when people wouldn't pay us.

These are our businesses. We have a $50 million-a-year grocery business; we have a wholesale grocery business. We have Redi-Mix Concrete. We have a number of enterprises of 2,040 employees. These are our government services. We operate the largest rural water district in the area. We are retrofitting all of our facilities to geothermal, ground source heat pumped geothermal with our own business.

This is my advice: press on. Three steps, two steps back is still one step forward so just stay at it. I've been at it a really long time. I love what I do. I'd do it if they didn't pay me. The first 11 years, by the way, they didn't pay me. But plan. And once you get plans, decide. Even if you decide wrong, it sets in motion the mechanics to get something done. But indecision just locks you up. Fix your constitution. Don't try to patch around it. We did it for years. Fix the constitution. If you have problems with not getting process at your tribe and it's because of the structure or because of something that is happening with the government that isn't fair or right or honest, fix the constitution. If you're not in the constitution-fixing business, you're not in economic development, you're not in self-governance, you're not a sovereign. Thank you."