Indigenous Governance Database

cultural identity

Indian Identity, Choice and Change: What Do You Choose?

Indigenous individuals and nations are faced with choices about identity, change and cultural continuity. The choices are not just mere faddish expressions but are deep decisions about culture, community, philosophy and personal and national futures. Many indigenous communities are divided over…

Survival of the Chickasaw Language

Chickasaw is an endangered language, but its chances of survival are much better thanks to the life's work of fluent speaker Catherine Willmond and linguist Pamela Munro. From beginners to conversational speakers, their books have become staples to students of the Chickasaw language everywhere.

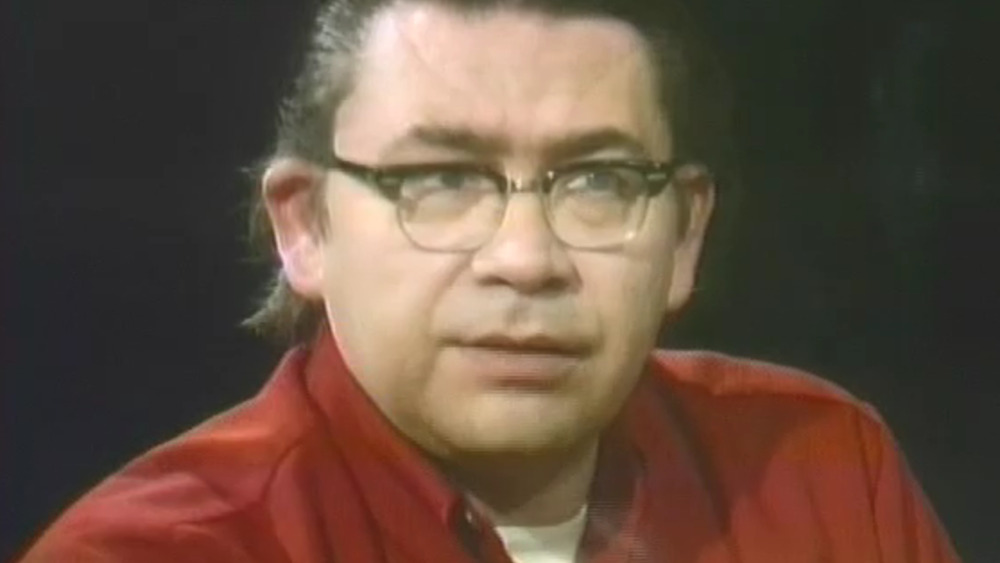

Richard Luarkie: Choosing to be Bitter or Better: A Perspective from a Pueblo Upbringing

Pueblo of Laguna Governor Richard Luarkie shares his rich Pueblo upbringing, a deep tradition of contribution to community, and inspiration to live a great life. Richard has a passion to contribute to global economic and community advancement using his Pueblo cultural values and teachings.

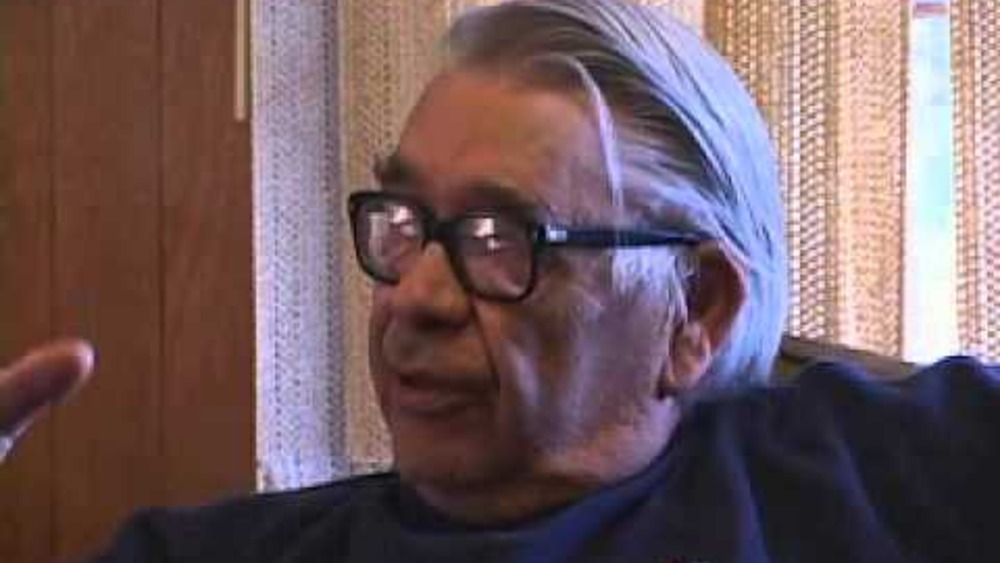

A conversation with Vine Deloria, Jr.

Indian writer Vine Deloria responds to questions from three interviewers, discussing the status quo of American writing about Indians. Deloria offers educational recommendations for Native Americans to counteract the predominance of Anglo viewpoints in the current literature.

The Best Practices in Rural Alberta Project

The Best Practices in Rural Alberta Project culminated in September 2012, after two and a half years of community engagement; research into the examination of leadership strengths and practices; incredible youth development; and video capture in preparation for a documentary film. This documentary…

Vine Deloria's Last Video Interview

American Indian author, theologian, historian, and activist Vine Deloria, Jr. (1933-2005) talks with documentary film producer Grant Crowell about traditional Indigenous governance systems and criteria for citizenship, the impact of colonial policies on tribal citizenship (specifically the effects…

Researchers Explore Roots of American Indian Resilience

Each week, inside the cafeteria of the New Directions enter, a Tucson behavioral health and substance abuse treatment facility, Tommy Begay channels heritage and history. He calls on the Navajo prayers and practices he learned from his great-grandmother to help others heal. “She taught me about…

Gregory Cajete: Rebuilding Sustainable Indigenous Communities: Applying Native Science

Dr. Gregory Cajete spoke as part of the "Alternative Forms of Knowledge Construction in Mathematics and Science" lecture series in Portland, Oregon which is co-sponsored by Portland State University and Portland Community College. The series features guest speakers who examine forms of mathematical…

Developing a First Nation Constitution

Chiefs, Administrators and Advisors discuss the importance of constitutions and the work involved in developing their own nation's constitution.

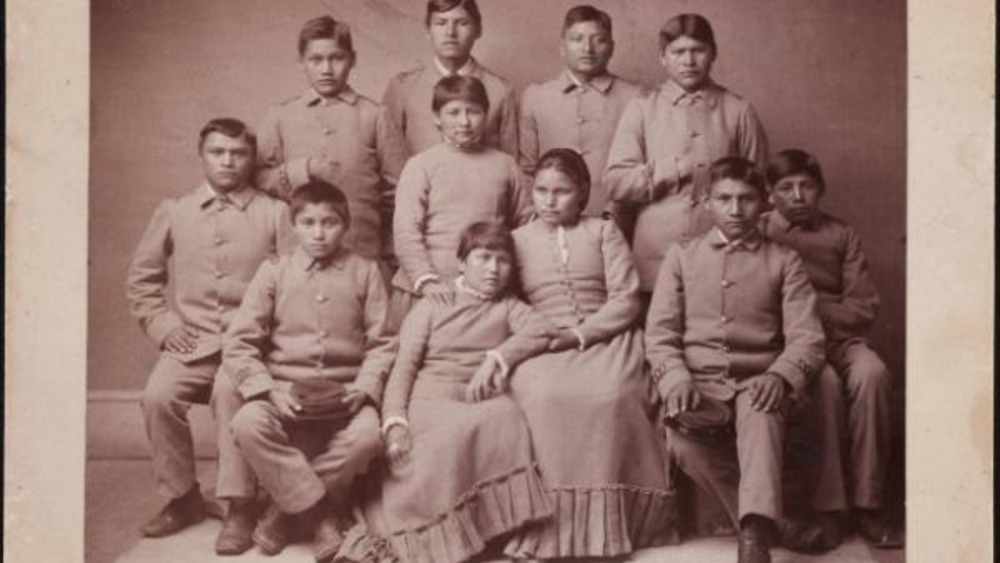

These Are My People...

This documentary short is the first film made by an all-Aboriginal film crew, training under the NFB's Challenge for Change Program. It was shot at Akwesasne (St. Regis Reserve). Two spokesmen explain historical and other aspects of Longhouse religion, culture, and government and reflect on the…

Native Report: Bush Foundation: Native Nation Rebuilders

On this edition of Native Report learn about the Bush Foundation's investment in sustaining the vitality of 23 Native communities across Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota. (Segment placement: 18:42-25:32)

NCFNG: Governance and Cultural Match

Taken from a 2008 event hosted by the National Centre for First Nations Governance, this video looks at the question: "How does a First Nation match governance with their culture and traditions?"

Ngurra-kurlu: A way of working with Warlpiri people

Ngurra-kurlu is a representation of the five key elements of Warlpiri culture: Land (also called Country), Law, Language, Ceremony, and Skin (also called Kinship). It is a concept that highlights the primary relationships between these elements, while also creating an awareness of their deeper…

Redefining Tigua Citizenship

The materials in this informational guide are designed to provide you with important background information ”such as Tigua history, tribal population profiles, and fiscal impacts” related to upcoming membership criteria changes. Project Tiwahu is an Ysleta del Sur Pueblo-wide initiative to reclaim…

An Anishinaabe Tribalography: Investigating and Interweaving Conceptions of Identity During the 1910s on the White Earth Reservation

This article explores the varied ways in which the Anishinaabeg of White Earth defined themselves during the early twentieth century. It consists of two primary parts. In part 1 I go beyond the artifacts in order to enliven the history, to offer an alternative way of remembering the past. In…

Navajo Cultural Identity: What can the Navajo Nation bring to the American Indian Identity Discussion Table?

American Indian identity in the twenty-first century has become an engaging topic. Recently, discussions on Ward Churchilla's racial background became a hotbed issue on the national scene. A few Native nations, such as the Pechanga and Isleta Pueblo, have disenrolled members. Scholars such as Circe…

Declaration of Tsawwassen Identity & Nationhood

We are Tsawwassen People "People facing the sea", descendants of our ancestors who exercised sovereign authority over our land for thousands of years. Tsawwassen People were governed under the advice and guidance of leaders, highborn women, headmen, and speakers through countless generations...

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …