Indigenous Governance Database

National Congress of American Indians (NCAI)

NCAI Task Force on Violence Against Women

Recognizing and acting upon the belief that safety for Native women rests at the heart of sovereignty, leadership from Native nations joined with grassroots coalitions and organizations to create an ongoing national movement educating Congress on the need for enhancing the safety of Native women.…

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: Mike Williams

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-…

Honoring Nations: Sarah Hicks: NCAI and the Partnership for Tribal Governance

Former NCAI Policy Research Center Director Sarah Hicks discusses the growth of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) and specifically its recent initiatives to support the nation-building and advocacy efforts of Native nations.

Honoring Nations: Juana Majel-Dixon: The Violence Against Women Task Force

Juana Majel-Dixon, Chair of NCAI's Task Force on Violence Against Women, reflects on the work of the Task Force on Violence Against Women and their efforts to push for passage of the Violence Against Women Act in Congress.

Frank Ettawageshik: Reforming the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Constitution: What We Did and Why

Frank Ettawageshik, Former Chairman of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBBO), discusses how LTBBO came to develop a new constitution and system of government, the key components of the LTBBO constitution, and how the new LTBBO constitution differs in fundamental ways from the old…

BIA Head Kevin Washburn Speaks to ICTMN About NCAI, Federal Recognition and More

ICTMN's panel consisted of Ray Halbritter, Publisher; Gale Courey Toensing, staff reporter as moderator; Ray Cook, Opinions Editor; Valerie Taliman, West Coast Editor; and Simon Moya-Smith, Correspondent. All participants asked questions at various points in the conversation (photographer Cliff…

Robert F. Kennedy's Legacy with First Americans

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s address to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) in Bismarck, North Dakota. I was in high school then. My memories are that of tribal leaders who came together from throughout the nation to discuss key issues of…

Wisdom From Mel: It's Okay to Not Know Everything

Mel Tonasket was not formally educated but he had lobbied and negotiated with Congressman and Senators. When Mel was in Washington D.C. he heard the fancy words from the Solicitors office. He was determined to fight for tribes and not let the “Suyapees” (Anglos) get the best of us — so when he…

Successful Tribes Are Reshaping Governance

American Indian communities are often offered up as the gold standard of dysfunction in America. With our high rates of entrenched poverty, we top the lists of addiction, suicide and other social ills. It’s platitude that, frankly, gets tiring to hear. We in the media like to describe the best and…

Stronger Ethics, Stronger Research: Tribal Governance as a Key Community Health Speaker

2015 CRCAIH Summit Keynote Address by Dr. Malia Villegas, National Congress of American Indians, Policy Research Center.

Indian Pride: Episode 106: Indian Advocacy

Indian Pride, an American Indian cultural magazine television series, spotlights the diverse cultures of American Indian people throughout the country. This episode of Indian Pride features Joe Garcia, former President of the National Congress of American Indians, and focuses on the topic of Indian…

NCAI - Footprints into the Future - 68th Annual Convention and Marketplace in Portland, Oregon

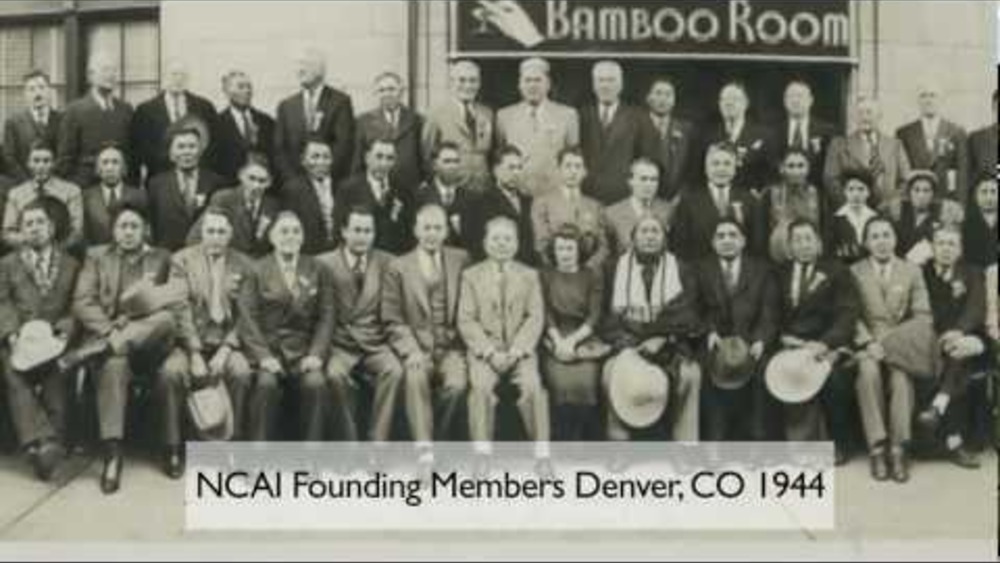

The National Congress of American Indians, founded in 1944, is the oldest, largest and most representative American Indian and Alaska Native organization serving the broad interests of tribal governments and communities. NCAI has grown over the years from its modest beginnings of 100 people to…

Native Report: Season 5: Episode 4

Come with us as we visit the Embassy of Tribal Nations in Washington, D.C., and talk with National Congress of American Indians President Jefferson Keel about its significance. We'll also meet Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs Larry Echohawk about his first year in office. Then we'll sit down…

Tribal Code Development Checklist for Implementation of Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction

This checklist (click to download) is designed as a tool to assist tribal governments seeking to develop tribal codes that implement special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction (SDVCJ) under section 904 of VAWA 2013. Tribal governments will likely be amending existing criminal codes, and every…

Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction

Tens of millions of Indigenous peoples inhabited North America, and governed their complex societies, long before European governments sent explorers to seize lands and resources from the continent and its inhabitants. These foreign European governments interacted with tribes in diplomacy, commerce…

Leadership and Communications in Indian Country

This four-page report outlines the key findings from interviews with five tribal leaders and tribal communications officers across the country. The conversations focused on exploring how communications helps in their daily work, how the communications playing field has changed over the years and…

Securing Our Futures

NCAI is releasing a Securing Our Futures report in conjunction with the 2013 State of Indian Nations. This report shows areas where tribes are exercising their sovereignty right now, diversifying their revenue base, and bringing economic success to their nations and surrounding communities. The…