Indigenous Governance Database

nepotism

John "Rocky" Barrett: Constitutional Reform and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation's Path to Self-Determination

In this wide-ranging interview with NNI's Ian Record, longtime chairman John "Rocky" Barrett of the Citizen Potwatomi Nation provides a rich history of CPN's long, difficult governance odyssey, and the tremendous strides that the nation has made socially, economically, politically, and culturally…

Leroy LaPlante, Jr.: Effective Bureaucracies and Independent Justice Systems: Key to Nation Building

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Leroy LaPlante, Jr., former chief administrative officer with the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and a former tribal judge, offers his thoughts on what Native nation bureaucracies and justice systems need to have and need to do in order to support…

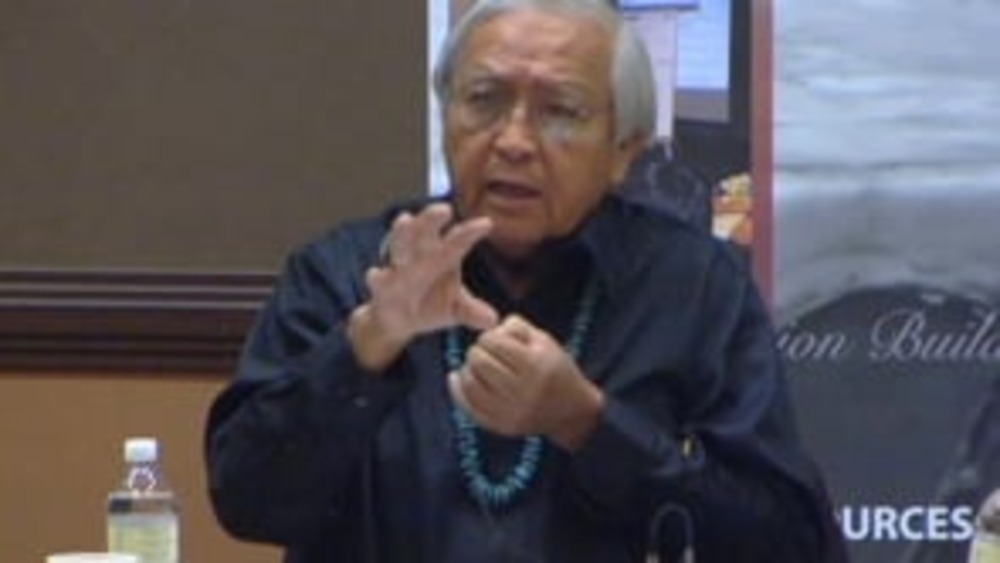

Peterson Zah: Addressing Tough Governance Issues

Former Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah shares the personal ethics he practiced while leading his nation, and discusses how he learned those ethics from his family and other influential figures in his life.

As old ways faded on reservations, tribal power shifted

Long before the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act transformed tribal government, before nepotism and retaliation became plagues upon reservation life, there were nacas. Headsmen, the Lakota and Dakota called them. Men designated from their tiospayes, or extended families, to represent their clans…