Indigenous Governance Database

sales tax

Navajo Nation Sales Tax

Challenges facing sovereign nations include how to support themselves financially, run their governments, and meet the needs of their peoples. In 1974, the Navajo Nation established a Navajo Tax Commission. Following a US Supreme Court decision affirming the Nation’s right to impose taxes, the…

Diane Enos: Building a Sustainable Economy at Salt River

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Diane Enos, President of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, discusses some of the many significant steps that Salt River has taken over the past few decades to systematically build a self-sufficient, sustainable economy.

Honoring Nations: Mark Graham: Navajo Nation Sales Tax

Mark Graham, former executive director of the Office of the Navajo Tax Commission, presents an overview of the Navajo Nation Sales Tax to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Mary Etsitty: The Navajo Nation Sales Tax

Mary Etsitty, Former Executive Director of the Office of the Navajo Tax Commission, discusses how and why the Navajo Nation sales tax was established, and how the Office of the Navajo Tax Commission works to consult and educate Navajo citizens about the need for -- and benefits of --…

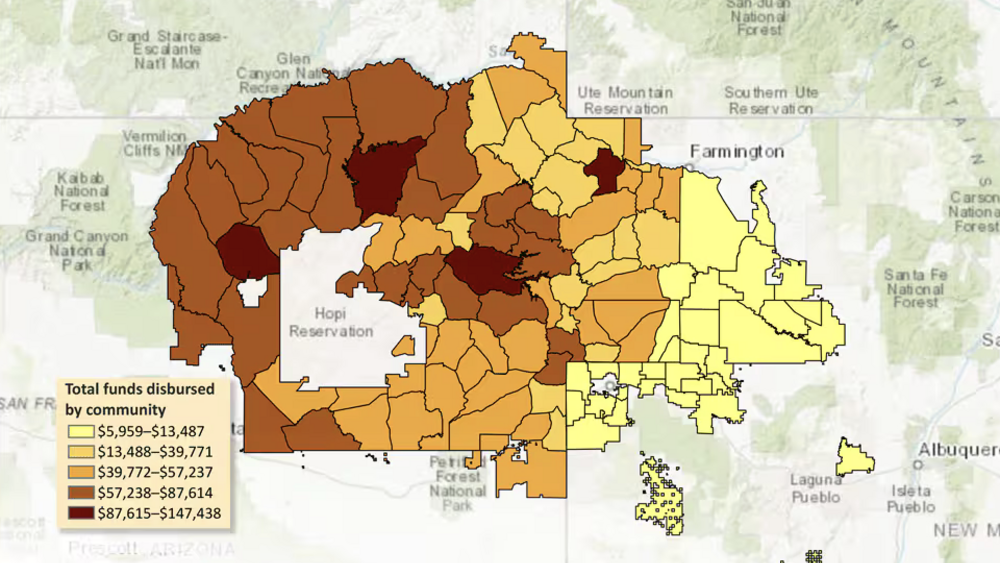

The Navajo Nation Healthy Diné Nation Act: A Two Percent Tax on Foods of Minimal-to-No Nutritious Value, 2015–2019

Our study summarizes tax revenue and disbursements from the Navajo Nation Healthy Diné Nation Act of 2014, which included a 2% tax on foods of minimal-to-no nutritional value (junk food tax), the first in the United States and in any sovereign tribal nation. Since the tax was implemented in 2015,…