Indigenous Governance Database

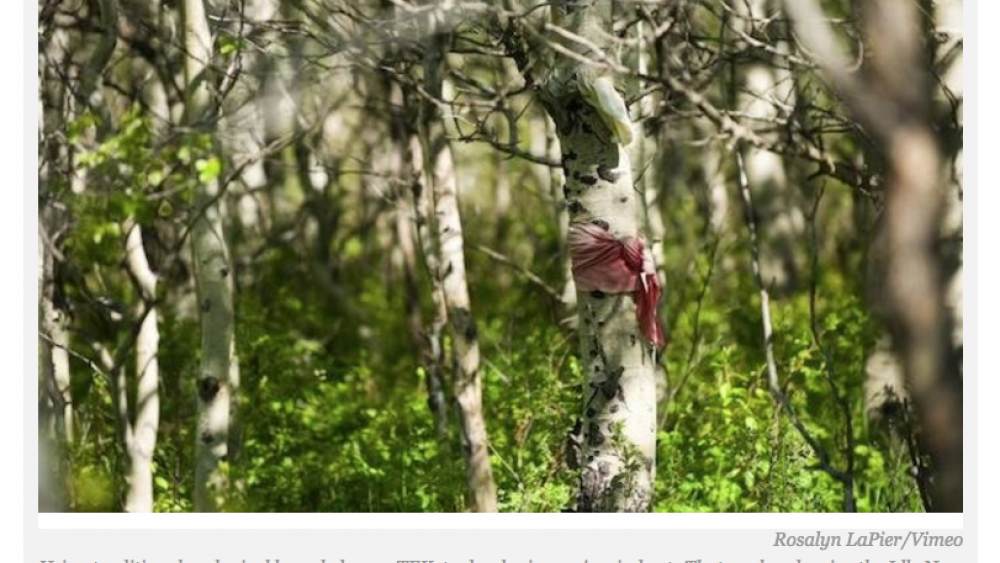

traditional ecological knowledge (TEK)

Applying the ‘CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance’ to ecology and biodiversity research

Indigenous Peoples are increasingly being sought out for research partnerships that incorporate Indigenous Knowledges into ecology research. In such research partnerships, it is essential that Indigenous data are cared for ethically and responsibly. Here we outline how the ‘CARE Principles for…

Story of Igiugig: Native Sovereignty in Alaska

This short film looks at how a sovereign Native people are planning for the future, as told through three short chapters: Chapter 1: Nunaput (Our Homelands) Chapter 2: Capricaraq (Persistence) Chapter 3: Pinarqut (Possibility)

Ahwahsiin (The Land/Where We Get Our Food)

Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and food systems are fast disappearing but are of the utmost importance, not only for sustaining Indigenous Peoples but also for providing alternative paradigms for coping with diverse ecosystems in a changing global environment. This research examines Blackfeet…

Coast Salish Gathering

Ecosystems in many parts of North America are under severe stress. Pollution, the overuse of natural resources, and habitat destruction threaten local flora and fauna. Conservation attempts often fall short because they target one species of site within an ecosystem. The Coast Salish Gathering…

Honoring Nations: Elizabeth Woody: Environment and Natural Resources

Elizabeth Woody reports back to her fellow Honoring Nations symposium attendees the consensus from the environment and natural resources breakout session participants, synthesizing their deliberations into four key elements for nation-building success in the environmental and natural resource…

Greg Cajete: Indigenous Paradigm: Building Sustainable Communities

Greg Cajete, Director of Native American Studies at the University of Mexico, shares his more than three decades of work and research on Indigenous epistemologies for human and ecological sustainability, and discusses the need for scholars, academic institutions, and others to fully embrace these…

Honoring Nations: Pat Sweetsir: Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council

Middle Yukon Representative Pat Sweetsir of the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council (YRITWC) discusses how and why the Indigenous nations living in the Yukon River Watershed decided to establish the YRITWC, and the positive impacts it is having on the health of the watershed and those who…

Idle No More: Decolonizing Water, Food and Natural Resources With TEK

Watersheds and Indigenous Peoples know no borders. Canada’s watershed management affects America’s watersheds, and vice versa. As Canada Prime Minister Stephen Harper launches significant First Nations termination contrivance he negotiates legitimizing Canada’s settler colonialism under the guise…

Klamath Youth Program Melding Science and Traditional Knowledge Wins National Award

A unique collaboration between a Klamath youth leadership development program and U.S. government researchers has won the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Partners in Conservation award for its use of traditional knowledge in conjunction with modern science. The Klamath Tribal Leadership…

8 Tribes That Are Way Ahead of the Climate-Adaptation Curve

Much has been made of the need to develop climate-change-adaptation plans, especially in light of increasingly alarming findings about how swiftly the environment that sustains life as we know it is deteriorating, and how the changes compound one another to quicken the pace overall. Studies, and…

Capturing Traditional Ecological Knowledge in the Torres Strait

Protecting and preserving cultural and ecological knowledge for the future is essential. The Torres Strait Regional Authority has recently developed and piloted a traditional knowledge database working with members of the Boigu Prescribed Body Corporate and the Malu Ki'ai Rangers. The database…

The Cutting Edge: Climate and the People of the Caribou

Wisdom of the Elders, Inc. (Wisdom) is producing a new series of Native American climate documentaries along with our fourth series of Wisdom of the Elders Radio Program. These oral history, cultural arts and climate science series feature the rich voices of more than 40 exemplary Native elders,…

Nunamin Illihakvia: Learning from the Land

"Nunamin Illihakvia: Learning from the Land" was an Ulukhaktok Community Corporation (UCC) led project funded by Health Canada in partnership with researchers from McGill University, the University of Guelph, and the University of the Sunshine Coast. The project brought together young Inuit adults…

Inuit Observations on Climate Change

This video documents the impacts of climate change from an Inuvialuit perspective. On Banks Island in Canada's High Arctic, the residents of Sachs Harbour have witnessed dramatic changes to their landscape and their way of life. Exotic insects, fish and birds have arrived; the sea ice is thnner and…

Swinomish Climate Change Initiative: Climate Adaptation Action Plan

In the fall of 2008 the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community started work on a landmark two-year Climate Change Initiative to study the impacts of climate change on the resources, assets, and community of the Swinomish Indian Reservation and to develop recommendations on actions to adapt to projected…

Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes Climate Change Strategic Plan

Overwhelming scientific evidence demonstrates that human inputs of greenhouse gases are almost certain to cause continued warming of the planet. (Environmental Protection Agency, 2013) The Northwest has already observed climate changes including an average increase in temperature of 1.5°F over the…

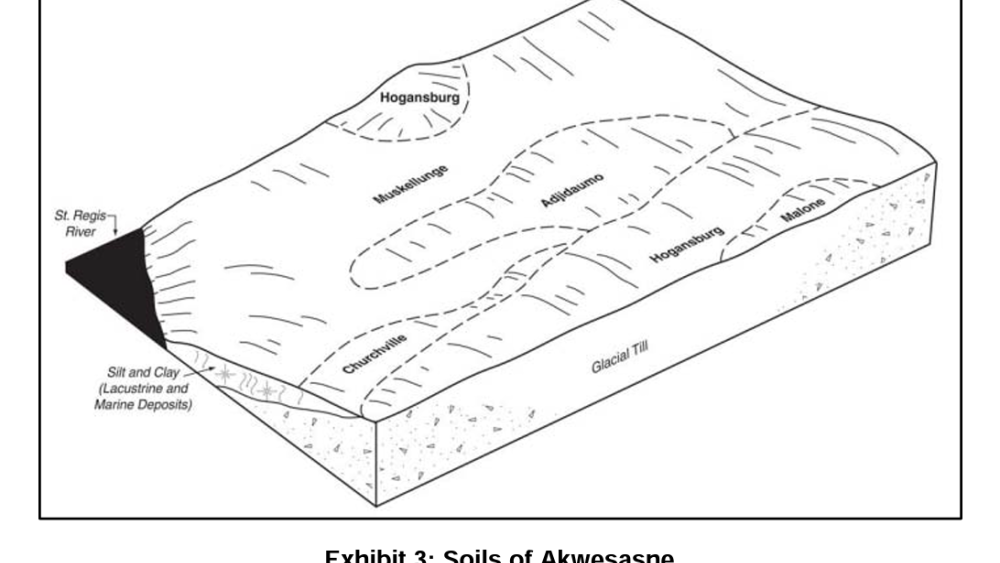

Climate Change Adaptation Plan for Akwesasne

The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe’s (SRMT) Environment Division is investigating the impacts of climate change on the resources, assets, and community of Akwesasne and is developing recommendations for actions to adapt to projected climate change impacts. This plan is a first step in an effort to…

Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Agroforestry

Communities around the world have practiced diverse and evolving forms of agroforestry for centuries. While both Indigenous and non-Indigenous practitioners have developed agroforestry practices of great value, in this publication, we focus on the role of Indigenous, traditional ecological…

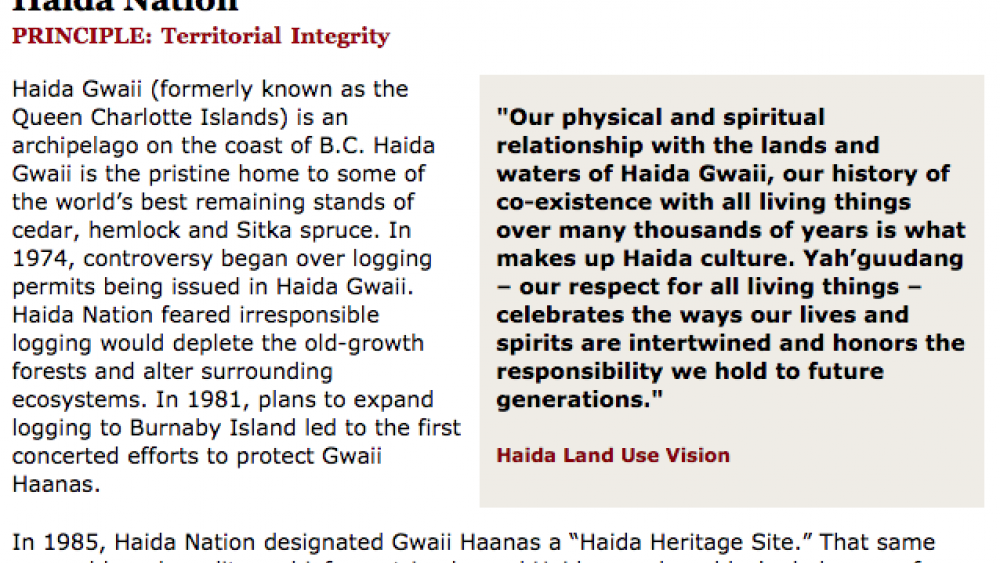

Best Practices Case Study (Territorial Integrity): Haida Nation

Haida Gwaii (formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands) is an archipelago on the coast of B.C. Haida Gwaii is the pristine home to some of the world's best remaining stands of cedar, hemlock and Sitka spruce. In 1974, controversy began over logging permits being issued in Haida Gwaii. Haida…

Asatiwisipe Aki Management Plan

The Asatiwisipe Aki Management Plan arises from several earlier initiatives by Poplar River First Nation. Poplar River has completed a variety of studies for the planning area, including traditional knowledge and community history interviews with Elders, traditional land use studies, archaeological…