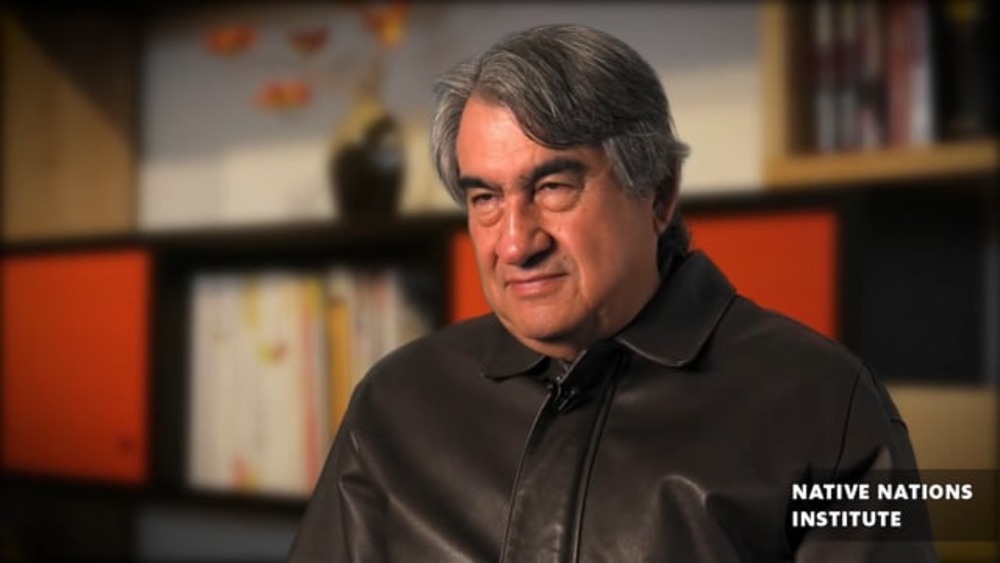

Greg Cajete, Director of Native American Studies at the University of Mexico, shares his more than three decades of work and research on Indigenous epistemologies for human and ecological sustainability, and discusses the need for scholars, academic institutions, and others to fully embrace these time-tested epistemologies as effective tools for combatting major issues such as climate change and global warming.

Additional Information

Cajete, Greg. "Indigenous Paradigm: Building Sustainable Communities." Department of Language, Reading and Culture, University of Arizona. Tucson, Arizona. April 23, 2007. Presentation.

Transcript

“Thank you, Candace and thank you Native students here at the University of Arizona for inviting me once again to give a presentation to your group and also to this group. As we say in my language [Tewa language], ‘Be with life, see that is the way it is.’ And I use this greeting, this way of opening my presentation today to sort of highlight, I guess, what I’m going to say to you and what I’m going to present to you in the context of this presentation. A lot of the work that I’ve been doing really within the last six years has been really around the notion of how do we develop a place for Indigenous thought, perspective, understandings within mainstream education. So hence, my role and my taking up the challenge of being the Director of Native American Studies at the University of New Mexico and actually attempting, not only with myself but also with some colleagues, to introduce in a kind of basic way this paradigm, these thoughts, these ideas into a Native/Western-based Native studies program.

So you can see that part of this has to also be about creating space and place within the academy, within the western academy for the thoughts and the ideas and the diversity of thought and idea that Native people have and have always had and have always brought to universities such as the University of Arizona and the University of New Mexico. And so my work today really is revolving around partly being an administrator. And all of those of you who have ever been an administrator know what that means. It really means lots and lots of time and meetings and working with political entities and coming forward and doing your presentations in hope of getting some money from some source to continue your program. The other part of it is internal work, which really requires you working with a variety of entities, particularly students and other faculty members to create a kind of openness first of all and secondly a kind of mechanism that allows you to begin to, in a sense, bring forward some of the ideas that are a part of what I call the Indigenous paradigm. And I’ve been working on this work actually for about 33 years now. It’s going to be 33 years that I’ve been ‘in the trenches’ as we say, a teacher starting really at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, as the high school science teacher and also the basketball coach and evolving into with the Institute into their college program, becoming the Dean of the Center for Research and Cultural Exchange there at the Institute and then also being the Chair of their Cultural Studies program before moving to the University of New Mexico 11 years ago now.

Part of my reason for taking on the leadership of the Native Studies program at the University of New Mexico is I felt that it was a time and a proper time to bring forward some of the ideas and perspectives that I had been working on as a cultural educator, as a Native educator within the secondary ranks and also within tribal college, as was the case with the IAIA [Institute of American Indian Arts] and bringing that into a university setting. And it’s not been without its challenges, it’s not been without much, much work but I think it’s becoming a point or a place where at least at the University of New Mexico where at least the Indigenous ideas and perspectives are becoming a part of the regular dialogue and discussion among students and Native faculty who are at the University of New Mexico. So the next stage of that is to make it a part of the dialogue of the University as a whole, which I think is probably going to be happening soon.

So my presentation today really is about what I would consider kind of my new work although it’s actually old work. It’s actually taking up some of the ideas and perspectives that I wrote in my first book Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education, in which I sort of began to take a look at what was indeed Indigenous education, what were its sources, what kinds of components did it have, what is the epistemology if you will of Indigenous education and how can we use it as a foundation to begin to create new curriculum from and in a sense to engender a kind of process of thinking that would allow the Indigenous perspective to have a place within mainstream education. And so Look to the Mountain is about philosophy, it’s about epistemology, it’s about a lot of things that deal with what I would consider foundational, philosophical, epistemological understandings that Indigenous people share not only here in the United States but actually worldwide with regard to language, with regard to community, with regard to understandings and relationships to environments in which they live, with regard to the arts and with regard to spirituality and with this whole notion of education.

And that then led to another book that I wrote, which is Native Science from a Native American Perspective which outlines some of the kinds of content that I began to use in a curriculum that I developed at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe those 33 years, beginning those 33 years ago. And in Native Science, what I talk about really is the Native ecological mind if you will, the perspectives and understandings that Native people have and have developed a knowledge base around that has sustained them through many generations within the context of the communities and the places in which they have lived. So the thoughts and ideas of Native Science are really about looking at and trying to understand and trying to bring forward some of those foundational ideas, those essential ideas into a dialogue and into a kind of context of education for the 21st century. And what I talk about in Native Science is really the understandings that Indigenous people have about their relationship not only to each other but to the world around them and especially to the cosmos. And so while I use primarily examples from Native communities in the United States and a few from Mexico and Canada, a lot of the thoughts and ideas and perspectives and orientations actually could be utilized for tribal peoples from Africa, from Asia, from Australia, from New Zealand and so on. [Okay. That makes a difference, doesn’t it?] So given that, given that understanding, what I want to do is give you some thoughts and perspectives related to that but let me finish these books up first.

After writing Native Science, I realized that a lot of people were beginning to talk about how to create curriculum that integrated or introduced Native content into the teaching of science and then I thought, ‘Didn’t I write something about that a few years ago?’ So I didn’t actually write my book on Native science modeling until about 1999 and it actually is my dissertation in a kind of synopsized form and sort of represents the idea, the concept and also a model that I had developed and utilized at the Institute of American Indian Arts. And so the book actually was a book about probably that I should’ve written first. Because the usual thing is that you do your dissertation and then you try to find a publisher and then you try to publish that. In those days, in 1986, you were hard pressed to find a publisher that even understood what you were talking about in the context of this kind of culturally based education perspective. So in those days it actually was pretty difficult so it wasn’t until 1999 that I actually got Igniting the Sparkle written into a book form. So for those of you that are educators, this is the book that’s kind of the recipe book that if you’re looking for some thoughts and ideas about how do you actually take these ideas of culturally responsive science and make them real for Native students in the classroom, this would be the book for you.

I don’t have a copy of my other book which is called A People’s Ecology, which is actually more along the lines of the presentation I’m going to give you today, but it’s called A People’s Ecology: Explorations in Sustainable Living and that’s published by, I believe the publisher is Clear Light Publisher for that. So hopefully you’ll also take a look at that. My last book, which actually did not get distributed very easily because my publisher, Kivaki Press, actually went out of business so I’m left with having to move this book around, but it’s called Spirit of the Game: An Indigenous Wellspring in which I take ideas and perspectives of Native games and begin to build a pedagogy of curriculum around them. And so what I find myself doing these days is actually beginning to create what I’m hoping is a kind of series of books and representations of the Indigenous thought and the Indigenous paradigm within these various kinds of contexts of education and hoping that people such as yourselves, students such as yourselves will take the challenge to sort of bring forward those ideas in your own ways, in your own perspective, in ways that make sense for you within the communities and schools that you teach in and to make them real once again within the context of Native life and Native education in the 21st century.

So with that I want to invite you to this presentation, "Indigenous Paradigm: Building Sustainable Communities," because what I’ve notice in all these years of working in this field is that there’s a kind of paradigm that’s beginning to form among Indigenous people, Indigenous scholars. And that paradigm is a paradigm that is both ancient and also new in many respects in the sense that it’s bringing forward some of the ideas and the principles and the understandings and the histories that Native people have always had and making them real in the 21st century. And so that evolving paradigm is something that Indigenous scholars around the world are participating in in a variety of different kinds of contexts and in a sense creating this kind of body of work and if you will in academic circles a kind of theoretical base essentially that Indigenous people are beginning to form that they can now begin to work from in a variety of different kinds of context; education, health, economics, governance and sustaining Indigenous communities ecologically and socially, culturally and spiritually and otherwise.

So the presentation today talks about that, that perspective, that understanding and I want to sort of take you through really for me it’s a kind of going back to some earlier thoughts and ideas, bringing them forward and working with them. So it’s a creative process on the part of myself as a scholar as I do this. But recreating Indigenous education is really for me one of the most important kinds of undertakings if you will in the sense that what we’re attempting to do is really begin to take a look at teaching and learning, which is transformative and anticipates change and innovation within the context of Native communities, Native education and more particularly within the minds of Native students. As I say there, ‘Indigenous education can integrate and apply principles of sustainability along with appropriate traditional environmental knowledge.’

The whole notion of sustainability is really important I think to understand today and one of the reasons why I’ve taken up this work again reminding you that part of my training is actually as a field biologist and that I’ve been following kind of the environmental crisis for 33-plus years. And the understandings we have now for instance with regard to global climate change, to the evolving environmental crisis, these kinds of considerations and understandings and the indicators that this was happening within the global living sphere that we call Mother Earth is and was there 33 years ago. The footprints, the evidence was beginning to evolve, we began to see the melting of certain glacier formations, especially in the Andes and beginning to see changes in climate and environment. A lot of this was happening 33 years ago and I remember as an undergraduate biology student studying global climate change and some of the possibilities that were being considered as ramifications of that kind of change.

So now we find ourselves in the year 2007 with no more excuses and literally with the evidence in such overwhelming amounts that global climate change has been happening, is happening, that human beings are largely responsible for it and the kinds of societies that we have created, the focus on fossil fuels and also our lifestyles, all of these have contributed really to this mounting evolving crisis. What we find ourselves in as education institutions and also as educators is that we haven’t necessarily anticipated this kind of process, this kind of challenge and certainly our institutions in many ways are not prepared to teach students in ways that are necessary to begin to have a real understanding of how to address some of the issues and the problems that global climate change will begin to gradually bring to us. So we’re finding ourselves in the midst of having to change in terms of a society, in terms of the way that we view and understand education but not really knowing how to change in many ways and not really understanding the ways that we need to begin to think and rethink the process of education today.

So my thesis has been and continues to be that Indigenous societies have always had a form of education that in a very practical and very direct way ensured that communities remain sustainable through environmental change and also through environments and maintained also a kind of relationship with the natural world that ensured that sustainability was really a possibility. And I’m thinking and I’m saying essentially that in today’s society, we have to begin to revisit some of these older traditions of knowledge, of education, of ways of being in community in order for us to begin to understand what we need to do in order to in a sense become sustainable within our environments once again. It’s a huge challenge and I think we’re just at the very beginning of realizing how huge it is and it is going to have an impact on all of our educational institutions and the way that we view education as a whole.

So I’m saying essentially that Indigenous education forms a foundation for community renewal and revitalization. So for Native communities this is…there’s even more, an even larger imperative. In many ways in Native communities we’ve been torn and have a history with education that is less than positive and we’re really just beginning to move into a stage where we’re able to at least have access to higher education, we have access to professional kinds of positions in government, in economics but it’s just at the very beginning process. And as we move into that, there’s always been the question, ‘How much of myself, my tradition, my community do I bring with me as I move into this world, this world of western education?’ But for me Indigenous education is one of the foundations of this community renewal and revitalization and this particular slide I think represents for me that understanding because it is about a kind of relational thinking, a relational position that you take both individually and as a community that ensures a kind of process of reciprocity and mutual relationship that ensures survival over the long period of time.

We’ve heard this many times in many phrases, in many ways, in many linguistic forms that Indigenous people have, ‘We are all related, we are all related, we are all related.’ And that idea of Turtle Island, which has been used many times as an ecological metaphor, which in biological circles has…is associated with what we call the Gaia Hypothesis, the idea that the earth is this one gigantic living system and that we live within that living system, that we’re related within that living system. Things that we do as human beings does have an impact in that greater living system which we call the earth. And so those ideas and those concepts, while in Western biology many times it was debated if there was even such a thing as a global system such as Gaia, such as the Greeks called 'Gaia.' Well, I think climate change and the effects of climate change really does show that the whole earth is enveloped in this living, interactive system and it’s a living system and we’re a part of that living system. And of course if you study Indigenous traditions, Indigenous languages, Indigenous stories, you begin to see that theme played over and over and over again represented from numerous kinds of perspectives that we are all related.

And so those ideas, I think, have to become a part of the new epistemology, I think you would say, that begins to guide us as educators, as institutions, as communities, because the truth is that our survival may depend on it, ultimately that our survival as human communities in this biosphere earth depends on it. So given that challenge, what do you do, because if you’re training people for a paradigm of economic development that in a very short time will probably not exist, at least not in the way that people are being trained for that. If you’re training people for positions or community development concepts that in very short time may not be in vogue, it may be totally obsolete, what then do you have to fall back on from the standpoint of educational strategy? So this is why I’m saying that the ideas that Indigenous people have are important. Traditional and environmental knowledge can provide models and creative insights necessary to renew communities, revitalize human communities and economies.

I think also we have to begin to take a look at how and also as I say up there, a long and hard look at the current educational, economic and community development policies, planning and processes which may many times make us complicit with the status quo and so this is a debate that happens certainly within the institution and certainly it’s a debate that happens among my faculty and my students is being complicit with your own, in a sense, demise, in some cases as it’s sometimes referred to. But I think that more it has to do with the orientation or the paradigm that we work from and beginning to take a look at that paradigm seriously and really, really, really thinking about it in terms of how it allows us or doesn’t allow us to become the kinds of sustainable entities that we wish to become. And so that’s the reason for that idea of complicity.

For me, as Director of Native American Studies, the problem becomes, how do I develop new Native studies, programming, courses, perspectives that build on this evolving paradigm that’s based on sustainability? And so the new kinds of things that it brings forward have to do with new kinds of courses, new kinds of delivery of courses, new ways of looking at courses, new connections of courses and faculty and community. How do you make that connection work? Again, a new kind of Native studies education predicated on guiding Native students towards this vision of health, renewed and revitalized, sustainable and economically viable Indigenous communities. So a lot of what is happening today in Native contexts and circles has to do with this concept of building Native nations. So when you go around and you talk with tribal entities, tribal governance, tribal communities and individuals within those communities, the overwhelming focus and intention is how do we sustain our communities in the face of a variety of different kinds of challenges. How do we self-determine within a political environment that doesn’t necessarily recognize our legal and our communal kinds of mandates to self-determine or wish to self-determine? So these are the kinds of issues that then become a part of the discussion about what is nation building, Native nation building in the 21st century? It’s not just about economics, it’s not just about governance, it’s not just about education but what is underlying all of those understandings and to understand that you have to go back and ask yourself the questions, ‘Well, what did Indigenous societies found their understandings of all of these different entities on, why were they doing it, what was the underlying kind of motivation for having systems of governance and having economies and having these systems of education?’ Well, it’s probably…more than likely it was to sustain one’s self. It goes back to sustainability. It goes back to sustainability. And sustainability is connected to another philosophical idea that we call ‘being with life’ or ‘life perpetuating,’ perpetuating the life of a community. So I began this session with the words ‘Be with life or with life…,’ which is basically the same as saying, ‘sustain life,’ and it’s a term that’s used in many Indigenous settings to create a mindset, a way of looking at what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.

So understanding this, I think, is a very important piece of this puzzle that we’re putting together with regard to, ‘What is the Indigenous paradigm and how is it related to Indigenous sustainable community development?’ We know that…when you study Indigenous cultures around the world, we know that there are certain kinds of characteristics of Indigenous sustainable communities that come at you all the time, that sort of reflect in a variety of ways and part of it has to do with this focus or refocus or constant focus on some sort of ecological integrity. Meaning that what you do as a community in some ways or another comes right back to some sort of an ecological connection, ecological sustaining connection to the environment, to the places, to the plants, to the animals, to the world in which you live. And so this is a part of that Indigenous epistemology and part of it is really start from the premise that what you do has integrity and honors life-giving relationships.

So now translating that ecological integrity into an action kind of statement and so if you were to ask the question, ‘Well, how do we develop Indigenous sustainable communities, what are their characteristics, how do we emulate that?’ Well, start with the premise that what you do has integrity and honors life-giving relationship. So what does that mean, how do you teach for that, how do you reflect that in the way you create your institutions, your economies? A sustainable orientation: building a process, which sustains community, culture and place. If you hear Native people talk both historically and also in contemporary settings, what you’re hearing many times when they talk about their communities, when they talk about the places in which they live, that’s what they’re saying; building a process which sustains community, culture and places, that connection.

Also, vision, purpose, vision and purpose. See what you can do in the light of revitalization of community. There’s things that can happen both individually and collectively that in a sense revitalize, that bring life back to something within the community. So if you begin to educate for those kinds of ideas, those kinds of actions, those kinds of ways of being in the world once again, those will more than likely happen. So we have today things like community-based education, we have things like service learning, we have a variety of different kinds of ecological restoration projects going on in a variety of different contexts, which in an of their essence bring life back to something, they revitalize something. And so that vision and purpose, see what you can do in the light of revitalization of community becomes a very important, imperative. Because what you work with when you’re developing sustainable community is you’re working with a culture, community and its resources and you begin to see those within the context of this greater challenge, this greater impetus of creating and teaching for sustainable community.

We know -- and as Native peoples we have always had -- a kind of spiritual purpose that has been and continues to be a kind of foundational understanding that we carry with us in a variety of contexts of education. So spiritual purpose especially has a very important role in this process of revitalizing Indigenous community. So this idea of cultural integration: actions which orient or originate, rather, through spiritual agency that stems from connections to a cultural way of being. That idea of Indigenous spirituality, it also has a practical purpose and it always has had a practical purpose. And that was to keep in the minds of a community that what you’re doing not only has spiritual purpose but it goes right back to that process, that understanding of being with life, seeking life or in some ways revitalizing, to revive or to bring life back to something. And so it also includes respect for all. Actions stem from respect for and celebration of community. This idea of respect, mutual respect, respect not only for each other in communities but also respect for the land, its plants, its environments, its whole environment if you will. And then engaging participation of community, the community is both the medium and the beneficiary of activities.

So the idea of education being of a community base first and foremost in Indigenous thinking, in the Indigenous paradigm, becomes a very, very important component of what I would consider the new kind of Indigenous education, which is largely community-based, not university-based; big difference between university base and community base. That doesn’t mean that you can’t have community in universities because you can and you do all the time, we create communities in universities, and what we’ve tried to do at the University of New Mexico Native American Studies is we’ve tried to create an Indigenous learning community that parallels the communities that the students and the faculty do come from. But what I’m talking about here is really that true Indigenous education happens within and through and around and with the Indigenous communities that it’s meant to serve.

If you study Indigenous education around the world, you begin to find that what moves it is relationality, that it’s based on a relational philosophy that relationship becomes one of the key principles of how things happen, how things get learned within those communities, how things get related to literally. And so when you take a look at Indigenous cultures around the world, it becomes a kind of tour of relationality in all of its many faces, all of its many representations. And so when you teach for relationality, it’s a very different kind of mindset than teaching for let’s say independence or rather individualistic kinds of endeavors or individualism. When you teach for relationship, you’re actually teaching for an understanding of how best to not only create relationship but extend it, maintain it and make it the foundation of all the things that you do. And so building upon and extending relationships are essential, process of this develop. Restoring and extending the health of the community is also part of that process ‘cause relationships can be positive or negative, can be healthy or not so healthy so relationship also has two sides to it. And you have to understand that part of what we’re doing is trying to create and maintain and extend relationships that are life giving so all of those things become important. Initiative should generate…the initiative should generate dynamic and creative process, the idea that relationship takes work, that it’s not just something that happens but rather is something that you have to work for and you have to constantly nourish because it’s a living process in and of itself.

There’s this business of commitment to developing the necessary skills, commitment to community renewal and revitalization, commitment to mutual reciprocal action and transformative change, that idea of commitment to each other and communities. There’s also the characteristic of Indigenous sustainable education in which the focus is to educate for the recreation of cultural economies around an Indigenous paradigm, so when we begin to look at things like economic development in the context of Native communities and we’re taking a look at some of the kinds of issues and challenges of global climate change, the dwindling resources, a variety of different kinds of ecological issues, then you have to begin to look at what it is that can begin to help people recreate some of the cultural ecologies or the cultural kinds of economies that once were a part of their life and their livelihood. So this is one of the reasons why Native people today, especially those that have a land base and resource base, fight so tenaciously let’s say for their fishing rights, fight so tenaciously for their hunting rights, fight so tenaciously for their gathering rights, fight so tenaciously for their rights to be…to continue let’s say traditional, environmental and/or lumbering practices or agricultural practices. All of that is based on this sentiment you see and this understanding. So begin by learning the history and principles of your own Indigenous way of sustainability, explore ways to translate that into the present, research the practical ways to apply these Indigenous principles and knowledge basis. So this is some of the kind of work that you would do in the creation of and moving forward to this kind of paradigm, if you will, of education.

Basic, shared Indigenous principles include many things. It’s place-based, resourcefulness and industriousness, collaboration and cooperation, integrating difference in political organizations, alliances and confederation building, trade and exchange. These are things that Native people have always done in the context of the kinds of ways in which they’ve created their sustainable communities alongside other sustainable created communities by Indigenous people. So in other words, Indigenous people have been creating these communities all along, but they haven’t been creating them in isolation. They’ve been creating them in relationship to other Indigenous communities, other regions, other places. And so we have a history of this, this relationship.

So what are some of the challenges to Indigenous sustainability today? In other words, if we were to create Indigenous communities, what are some of the kinds of issues that we would face immediately in attempting to do that? Well, establishing political self-determination is one of the issues that we continue to work with and continue to have to in some ways defend and find ways to express. Decolonization and culturally responsive education; decolonization in the sense that it’s a kind of re-education process for us as Indigenous people to begin to take a look at some of our own complicity and some of the issues of colonization and trying to begin to not only understand that but to reverse that. And part of the ways that you reverse that is through culturally responsive education, beginning to take a look at that paradigm seriously, express it, maintain it, extend it.

Also taking a look at economic exploitation, diverse and competing ideologies in some of the political restructuring that happens in Native communities and happens as a result of federal Indian policy, that mitigate against communities creating themselves or recreating themselves as sustainable communities. Other issues include the very fact that we have individual diversities among Native peoples, identity redefinition, creating formal and informal institutions also become a part of the task of in a sense retooling ourselves and retooling our view of ourselves towards this Indigenous paradigm. Challenges also include the cultural, the social, the political and the spiritual fragmentation that all of us experience in communities and also in different kinds of situations of community building. Creation of formal and informal institutions, which advance sustainability: some universities, some colleges, some tribal colleges are beginning to do some of this kind of work but much work needs to be done because it does require new kinds of courses, new kinds of configuration of courses, in some cases even maybe new institutions that begin to look at this kind of advancement of sustainability. Challenges also include flowing with heterogeneity, complexity and differentiation. As modern people living in a modern society today, Indigenous people have been affected by all of these challenges of differentiation and changes of perspective and understanding. So we have to begin to look at that and see how that has affected us.

And then also in many cases it’s also a matter of political restructuring both internally and externally. But what do we have going for us? You can’t just leave it there and say, ‘Well, these are all the challenges, let’s just give up and forget about it.’ The fact is is that as Indigenous communities we do have resources that we can actually draw on now and these include things like our extended family, clans and tribes, which are still functional in many Native communities, which are organizations of people, related people. We do have still community in bits and pieces in places. We also have places and regions in which those communities are situated and which can be affected in a sustainable way. We have political, social, professional and trade organizations that can be mobilized in a variety of ways to support sustainability of communities. We have had always co-ops, federations and societies which have developed around the ideas of how to perpetuate in many cases community activities and even the corporation, which can be sustainable if founded on principles of sustainability. Now that’s a controversial statement that I make there because some would say you can’t teach corporations new tricks. Well, the corporation believe it or not is actually a kind of community. It’s a very, very self-centered community maybe -- focused on maybe just one goal -- but the fact is that it is a community. Corporations function as communal entities and so beginning to take a look at what is the sustainable corporation. Does it exist, can it exist? I dare say that it probably has to begin to exist if our future is going to be one that is going to be sustainable. In other words, corporations do have to become more sustainable and more…and have more ownership towards community goals. And so there’s a whole group of people that are beginning to write about, ‘What is the sustainable corporation? Can it even exist?’

So finally Indigenous food traditions, Indigenous family, Indigenous communities, Indigenous relationship, Indigenous health, Indigenous education, these are all areas, these are like different seeds. Remember I showed you some corn cob and there were seeds on it and there were different kinds of…hues of the kernels of the corn. They were different, but they all were on the same corn cob and that principle in biology is called unity and diversity. You have a unity in the form of the community itself but you have diversity in terms of the individual kernels of corn which will turn into individual corn plants. Well, the fact is that we have individual kernels around which ideas, concepts and education around Indigenous sustainability can actually be taught, can actually be experienced, can actually be extended and ultimately it’s coming back to that old, very ancient notion of a celebration of life or an extension of life. ‘Be with life’ was what I started the presentation with and that idea is I think an idea that has never grown old. It may have been subsumed by other kinds of understandings, other kinds of ways of looking at things, other perspectives, but the fact is that human beings live in communities and part of the real deep instinct, I think, that we have as human beings is that we extend life and that we’re a part of this greater life process, which is the earth’s life process.

And so this is a vision of education. I’m not saying that it exists in any place right now, maybe in a few Indigenous communities that haven’t been too assimilated. It may exist somewhere in the world. It doesn’t necessarily exist in its pristine form as it once existed and I’m not really saying that we need to go back to that way of living but we have to understand what that way of living had to teach us. And I think more particularly the principles of knowing and understanding what it takes to be sustainable in a world that is under great crisis today and will continue to be under great crisis in the succeeding generations. So it’s both a challenge, it’s both a vision, it’s a perspective, it’s new work that I think myself and others are beginning to undertake. It’s really almost like a research question. What is the sustainable, Indigenous community? Can it exist, does it exist, where does it exist, how can it exist? And more particularly the education question is how do we educate for that or at least educate towards that? Because I think ultimately the next generation of scholars, of foundations of education have to be ecologically sound, they have to be about environmental sustainability. It can’t be just a marginal kind of undertaking but rather it has to be I think an integral part of education in the 21st century. And I will bet you that you’ll begin to see not only writing and not only new kinds of ideas coming forward because now they have to around these issues, around these perspectives.

So for Indigenous people, what is Indigenous education? And it’s something I started in my dialogue in Look to the Mountain. Where have we been? Which is our traditions, our ways of life and understanding those. Where are we now? Which is really the context in which we all find ourselves with the challenges, with the kinds of institutions and then we have to have a vision of where we’re going to go in the future. What are the possibilities and what are the paths that we need to get there? So that’s what Look to the Mountain was. Look to the Mountain was a metaphor for, ‘Where have we been, where are we now and where can we go in the future,’ in terms of Indigenous education. So I leave you with that question. It’s a hard question. It’s not an easy one. It requires multiple heads to think about it. It requires a community to do it.

There was the old saying that I used in Look to the Mountain that ‘Indigenous education is about finding one’s face,’ which is to find one’s identity, that’s what we call identity today, ‘find one’s heart,’ which is that passionate sense of self that moves you to do what you do, ‘to find one’s foundation,’ which is in today’s language vocation, that kind of work that allows you to most completely express your heart and face, and that all of that is within a relational circle. That it’s first of all relationship between yourself and yourself, which is self knowledge; relationship between yourself and your family, your clan, your tribe, the place in which you live, and then finally the whole cosmos and that it is towards an understanding of becoming complete as a man or as a woman. And you see that whole thing is a sphere and it’s a sphere of relationality, a relationship, and that’s an Indigenous paradigm that is reflected in a variety of different ways in Indigenous philosophies about what it is to be educated, what it is to be a person of knowledge. So these are ideas that I think are very important to begin to consider as we move into the 21st century and have to really rethink the way we’ve created our institutions, the way we’ve educated, the way we have been educated, the way we understand the process and the importance of community within education and the importance to in a sense come back to that.

So with that I’d like to thank you and I’m now open for questions. I should also say that since this is being filmed that the slides that I’ve shown you are actually archival slides that comes from the University of New Mexico and so those are slides that just were meant to bring your thoughts and your ideas to those points, those perspectives. They’re based on Southwestern Pueblo life and tradition but it could just as easily have been Navajo, slides of Navajo life, slides of Apache life, slides of Pawnee life, slides of Algonquin and other peoples’ lives, other Indigenous peoples from all over the world. The same ideas and concepts I think have a similar kind of play within those societies. While we are different even among Indigenous people, we do share some common ideas and understandings and I think that’s what in a sense allows us to maybe call ourselves 'Indigenous.' So with that I’ll take some questions, comments, perspectives.”