Indigenous Governance Database

National

President's State, Local, and Tribal Leaders Task Force on Climate Preparedness and Resilience: Recommendations to the President

As the Third National Climate Assessment makes clear, climate change is already affecting communities in every region of the country as well as key sectors of the economy. Recent events like Hurricane Sandy in the Northeast, flooding throughout the Midwest, and severe drought in the West have…

Sustaining Indigenous Culture: The Structure, Activities, and Needs of Tribal Archives, Libraries, and Museums

Sovereignty, self-determination, and self-governance are primary goals of Indigenous nations worldwide and they take important steps toward those goals by renewing control over their stories, documents, and artifacts. To better support it, a core team of Native professionals formed the…

Supplemental Recommendations of Tribal Leaders on the President's State, Local, and Tribal Leaders Task Force on Climate Preparedness and Resilience

Tribes and Alaska Native Villages feel the effects of a changing climate in ways that are unique to their ways of life, geography, and relationships with the Federal Government. According to the National Climate Assessment, “the consequences of observed and projected climate change impacts have and…

Culture and Law: Preliminary Findings in a Review of 100+ Tribal Welfare Codes

Over the last 35 years numerous tribes have created their own child welfare standards. By crafting child welfare codes that balance traditional culture and contemporary needs, tribes both protect member children (and their families) in culturally appropriate ways and reaffirm their sovereign…

Report on Best Practices in Developing Effective Processes of American Indian Constitutional Reform

The Executive Session on American Indian Constitutional Reform is a national working group of constitutional reformers from 12 American Indian nations and leading academics. The Executive Session meets twice a year to rethink strategies for strengthening tribal constitutions and constitution-making…

Resource Center for Implementing Tribal Provisions of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): Webinars

The Intertribal Technical-Assistance Working Group on Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction (ITWG) has participated in a series of webinars focused on defendants' rights issues (including indigent counsel); the fair cross section requirement and jury pool selection; prosecution skills;…

In Defense of Tribal Sovereign Immunity: A Pragmatic Look at the Doctrine as a Tool for Strengthening Tribal Courts

Although the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity was recently upheld by the Supreme Court in Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, its existence continues to be attacked as antiquated and leading to unfair results. While most defenses of tribal sovereign immunity focus on how the doctrine is a…

Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction

Tens of millions of Indigenous peoples inhabited North America, and governed their complex societies, long before European governments sent explorers to seize lands and resources from the continent and its inhabitants. These foreign European governments interacted with tribes in diplomacy, commerce…

Sovereignty, Economic Development, and Human Security in Native American Nations

This study explores elements of the sovereignty dynamic in the government-to-government relationship between the United States and Native American nations to assess 1) what benefits Tribal communities glean from this unique relationship; and 2) whether enhanced Tribal sovereignty can enhance…

On Improving Tribal-Corporate Relations In The Mining Sector: A White Paper on Strategies for Both Sides of the Table

Mining everywhere is inherently controversial. By its very nature, it poses hard economic, environmental, and social tradeoffs. Depending on the nature of the resource and its location, to greater or lesser degrees, the mining process necessarily disturbs environments, alters landscapes, and…

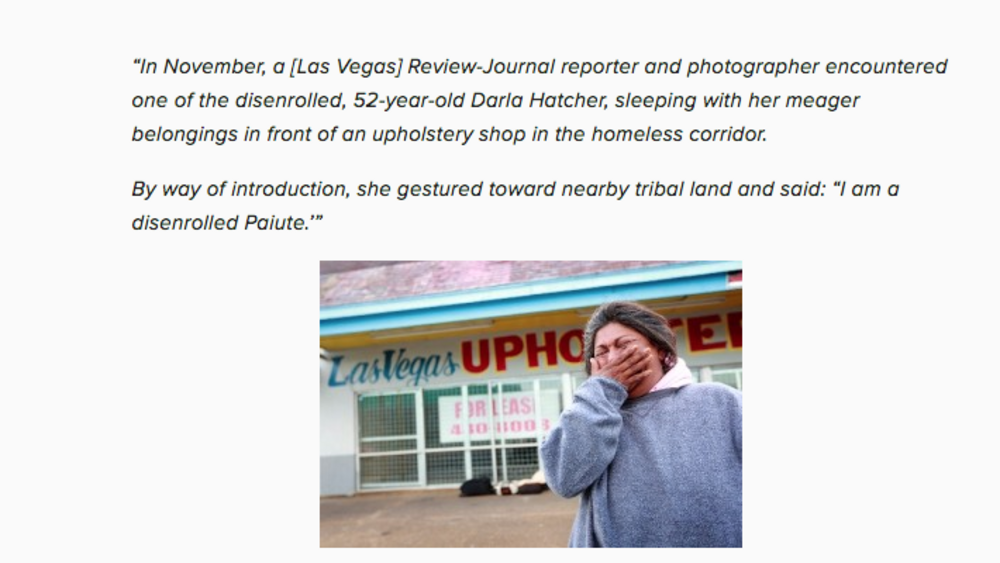

Tribal Per Capita Poverty - How About Disenrollment Bankruptcy?

“In November, a [Las Vegas] Review-Journal reporter and photographer encountered one of the disenrolled, 52-year-old Darla Hatcher, sleeping with her meager belongings in front of an upholstery shop in the homeless corridor. By way of introduction, she gestured toward nearby tribal land and said…

Understanding the history of tribal enrollment

It's difficult to talk about tribal enrollment without talking about Indian identity. The two issues have become snarled in the twentieth century as the United States government has inserted itself more and more into the internal affairs of Indian nations. Ask who is Indian, and you will get…

Effective Tools for Communications and Leadership in Indian Country

A thirty-six page toolkit, this NCAI publication outlines the tools, tactics, and strategies from tribal communications experts. The toolkit aims to help tribal leaders and Indian Country advocates in ever changing media and communications landscape.

Peacemaking and Conflict Resolution: A List of Resources

The Native American Rights Fund's National Indian Law Library provides a comprehensive list of relevant news stories and academic articles on the peacemaking mechanisms and conflict resolution approaches of Native nations.

Tribal-citizen entrepreneurship: What does it mean for Indian Country, and how can tribes support it?

The following feature, a special to Community Dividend, is the condensed version of a speech Professor Cornell delivered at the Montana Indian Business Conference in Great Falls, Montana, on February 2, 2006. The conference, which was cosponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, focused…

What Determines Indian Economic Success? Evidence from Tribal and Individual Indian Enterprises

Prior analysis of American Indian nations' unemployment, poverty, and growth rates indicates that poverty in Indian Country is a problem of institutions particularly political institutions, not a problem of economics per se. Using unique data on Indian-owned enterprises, this paper sheds light on…

Securing Our Futures

NCAI is releasing a Securing Our Futures report in conjunction with the 2013 State of Indian Nations. This report shows areas where tribes are exercising their sovereignty right now, diversifying their revenue base, and bringing economic success to their nations and surrounding communities. The…

Good Practice Guide: Indigenous Peoples and Mining

It is important that companies take the time to properly understand the communities they work with including their particular context, concerns and aspirations. This Guide aims to assist companies to achieve those constructive relationships with Indigenous Peoples.

Tribal sovereign immunity: An obstacle for non-Indians doing business in Indian Country?

Native American tribes consider sovereign immunity to be crucial for the protection of tribal resources and the promotion of tribal economic and social interests. Because of the uncertainties surrounding this doctrine, however, this very same tool of self-determination may be viewed as a…

Statement before the United States Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Oversight Hearing on Economic Development

Why is it that, amidst the well-documented and widespread poverty and social distress that characterize American Indian reservations overall, an increasing number of Native nations are breaking old patterns and building economies, social institutions, and political systems that work? What explains…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 9

- 10

- 11

- …