Indigenous Governance Database

Donald "Del" Laverdure

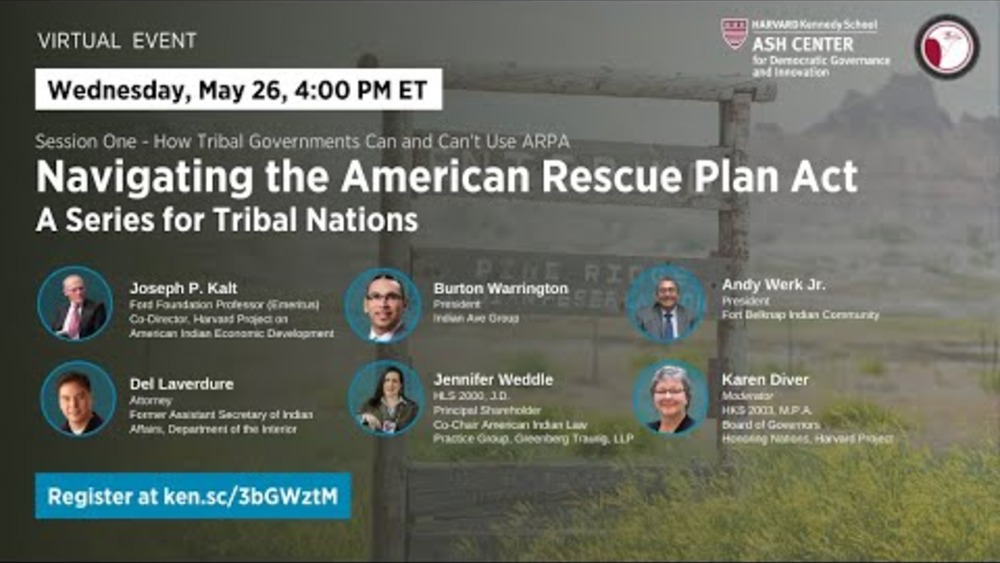

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 1: How Tribal Governments Can and Can't use ARPA

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides the largest single infusion of federal funding into Indian Country in the history of the United States. More than $32 billion is directed toward assisting American Indian nations and communities as they work to end and recover from the devastating COVID-…

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 3: A Conversation with Bryan Newland - How Tribes Can Maximize their American Rescue Plan Opportunities

From setting tribal priorities, to building infrastructure, to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

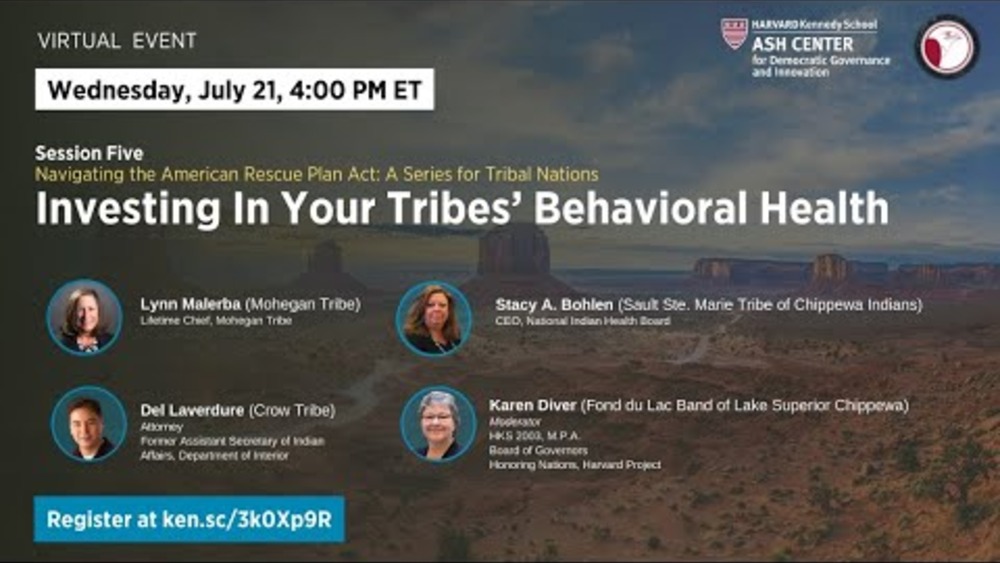

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 5: Investing in Your Tribes' Behavioral Health

From setting tribal priorities, to building infrastructure, to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

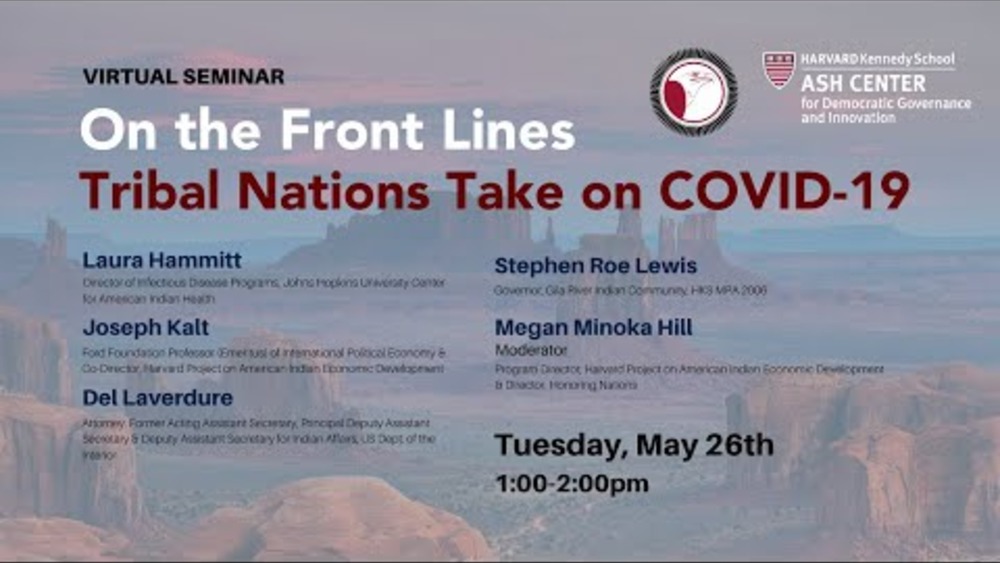

On the Front Lines: Tribal Nations Take on COVID-19

Like governments around the world, America’s 574 federally recognized tribal nations are racing to protect their citizens from the coronavirus. Impacting tribes at a rate four times higher than for the US population, the pandemic is testing the limits of tribal public health infrastructures.…

Donald "Del" Laverdure: Nation Rebuilding through Constitutional Reform at Crow

In this in-depth interview with NNI's Ian Record, Donald “Del” Laverdure, a citizen of the Apsáalooke Nation (Crow Tribe) and former Chief Justice of the Crow Tribe Court of Appeals, discusses his nation's monumental effort to discard a constitution and system of governance that were not…

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "What Strong, Independent and Legitimate Justice Systems Require"

Native leaders and scholars discuss what Native nations need to do to create strong, independent and culturally legimate justice systems.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Constitutions: Reflecting and Enacting Culture and Identity"

Hepsi Barnett, Frank Ettawageshik, Greg Gilham and Donald "Del" Laverdure offer their perspectives on the opportunity that constitutional reform presents Native nations with respect to reintegrating their distinct cultures and identities into their governance systems.