In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Sophie Pierre, longtime chief of the Ktunaxa Nation, discusses Ktunaxa's ongoing effort to reclaim and redesign their system of governance through British Columbia's treaty process, specifically Ktunaxa's citizen-led process to develop a new constitution that reflects and advance Ktunaxa cultural values and its priorities for the future.

Additional Information

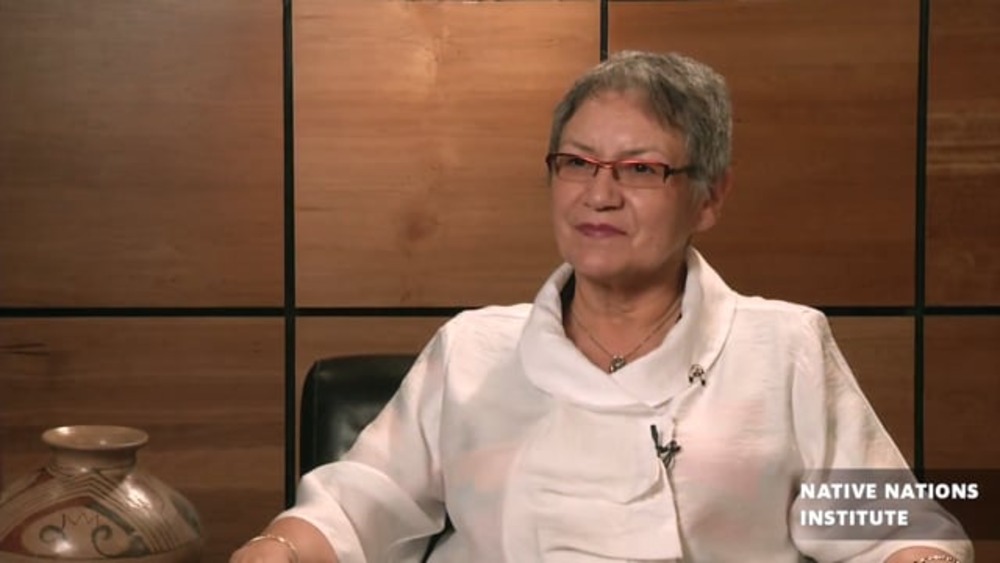

Pierre, Sophie. "Enacting Self-Determination and Self-Governance at Ktunaxa." Leading Native Nations interview series. Native Nations Institute for Leadership, Management, and Policy, The University of Arizona. Phoenix, Arizona. October 21, 2008. Interview.

Transcript

Ian Record:

“Welcome to Leading Native Nations, a program of the Native Nations Institute for Leadership, Management and Policy at the University of Arizona. I’m your host, Ian Record. Today, I am honored to welcome to the program Sophie Pierre, who for the past 26 years has served as chief of the St. Mary’s Indian Band in British Columbia. She also serves as the chairperson of the Ktunaxa Nation Council, an organization formed in 1970 to promote the political and social development of its five member bands, which includes St. Mary’s. She is the past co-chair of the First Nation Summit and a recipient of the Order of British Columbia. Last but certainly not least, Chief Pierre also serves as co-chair of the International Advisory Council for the Native Nations Institute. Welcome, Sophie and thank you for joining us today.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Thank you very much, Ian. It’s a pleasure to be here.”

Ian Record:

“Sophie, I’d like to start with a question that I ask all of the guests on this program and that is how do you define sovereignty and what does it really mean for Native nations?”

Sophie Pierre:

“I think that what it really means was explained by chief who’s since left, his name was Joe Mathias, he was chief of Squamish and he always said that sovereign, that exercising sovereignty was that the people who are going to live with the results of a decision are the people who make the decision and to me that’s what sovereignty has always meant is that we are responsible for our own lives, we make our decisions and we’re the people that suffer the consequences of those decisions.”

Ian Record:

“Okay. As a follow-up to that, how do you define a healthy Native community? What does that look like at Ktunaxa?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, we’re, I think that the healthy Native community is something that I can actually see coming into fruition and that’s a community where the decisions that are going to affect that community are being made right at the community level and that they’re being involved or everyone in the community is being involved in those decisions. The treaty process that we’ve been going through has allowed us, I think, that opportunity to engage our citizens in many aspects of life, not just the social programs that used to be the norm. Now we’re talking about making land-use decisions and far reaching planning for development and those are all at the community level, at the citizen level that those decisions are being made and that’s really where I see a healthy community is where the citizenry are engaged and they’re making, they’re charting their own course for the future.”

Ian Record:

“So essentially, regaining ownership in their own future and in the government that’s going to make that future happen.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Exactly. Yeah, exactly. It’s that regaining of ownership and it’s that recognition that the decisions that you make, that they’re, it’s the people who are going to live with the consequences that make those decisions.”

Ian Record:

“You are the chief, as I mentioned, of the St. Mary’s Indian Band and also Chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council. Can you tell us a bit about the St. Mary’s Band, the Ktunaxa Nation, and their relationship to one another?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, the Ktunaxa Nation is the Canadian relative of our nation, which is like many Indian nations in North America, was divided when the 49th Parallel was put in and the two countries were created of Canada and the United States, because we have Ktunaxa speaking people in Montana, Idaho and in British Columbia. So we are the Canadian group of Ktunaxa and the St. Mary’s Indian Band is similar to the other four bands within our nation. Those were created by the federal government when they were creating the Indian reservations just after the country of Canada became the Dominion of Canada. And so the St. Mary’s Indian Band is one of five Indian bands within our nation council and we have, our Indian reserve lands are held in trust by the government for our use and benefit as are all Indian reserve lands in Canada.”

Ian Record:

“The Ktunaxa Nation and I hope I’m pronouncing that correctly, ”

Sophie Pierre:

“Yes, you are.”

Ian Record:

“, or pretty closely anyway, works to advance the strategic priorities of its member bands through what it calls the 'Four Pillars.'“

Sophie Pierre:

“That’s right.”

Ian Record:

“What are these pillars and how does the Ktunaxa Nation support or advance those pillars?”

Sophie Pierre:

“The Four Pillars are lands, first and foremost, are our lands and our resources, that determines who we are as Ktunaxa and we know where our lands are because it’s in those, that territory where we have place names and when I’m describing our lands, that’s, I can give the place names, sort of the boundaries of it. And it’s our people, always, it’s the people of Ktunaxa ancestry, Ktunaxa speaking people and it’s our governance and then it’s our, the sort of overall what holds us together in terms of our, I’m wanting to talk about our social programs, but I don’t want to call it social programs. It’s the umbrella that provides services to the people. So it would be like our administrative side. So those are the four main pillars. And we determined that through about two years of discussion, of conversation with our people as we started to create our vision statement and that’s where that came from because we talk about strong, healthy people speaking our language and living in our traditional territory and sharing our resources and in a self-governing manner. That is our mission statement and it encompasses the four pillars.”

Ian Record:

“The Ktunaxa Nation, on behalf of its five member bands, has for several years now been engaged in comprehensive constitutional reform and governmental reform as well, which is very different in not only process but also terminology from constitutional reform by Native nations in the United States. What does the constitutional reform process entail for First Nations in Canada and what does it really look like?”

Sophie Pierre:

“It’s different in different parts of Canada. What we’re involved in in British Columbia through the treaty-making process has made it more, has made it, I think a little bit easier for us to actually get into the constitutional reform and to, maybe not so much constitutional reform as building a constitution, rebuilding our constitutions and that’s the discussion that I talked about earlier where I related that to sovereignty where there’s an engagement of your whole citizenry in order to develop that. So now we see, as we form our, build our constitution that that is being brought back to our citizens on a regular basis so they have real input into that. And what it’s going to be at the end of the day is, well, like what constitutions are, they’re the basis, they form the basis of our government and we are looking at recreating, rebuilding the governing structures that we had as Ktunaxa before contact. We, as an Indian band, of course, have been affected by the Department of Indian Affairs and their legislation called the Indian Act. We have, and I have served as such, the Indian Act-elected Leadership. And so you had mentioned that I’ve served 26 years as a chief, that’s something that I’m very grateful for having had that opportunity, but it was through the Indian Act process where we have elections. My grandfather was the last non-elected chief in our community and he stepped away from his position and passed it on in the traditional manner in 1953, but the Indian agent came in and said that the people had to do a vote according to the Indian Act, that that wasn’t, the way that we used to do it wasn’t considered democratic or whatever. So they changed it and now we’ve been having these Indian Act elections. So the, it’s sort of a melding of the way we did things traditionally to the way that we see us being able to move forward and it’s taking the 'Four Pillars' that have been developed by our people in our mission statement and determining a way that we can bring life to that mission statement so it’s not just on a piece of paper hanging on a wall -- it’s something that we live every day.”

Ian Record:

“So what compelled the Ktunaxa Nation to undertake not just constitutional reform, but as you say, but essentially rebuilding the constitution from the ground up? So, what compelled the nation to chart that course and what have been the major outcomes thus far?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, the, I keep mentioning the treaty process that we’re in and that really was sort of the trigger. I think that we may have been involved in this kind of discussion anyway, but probably at a lot slower pace and probably with not as much engagement of our total citizens as we have been able to through the treaty process. I think the most exciting outcome that this, that we’ve seen is the understanding and the, I don’t want to use the word 'buy-in,' but I can’t think of what else to call it, but people really believe that whether or not we sign a treaty with the other levels of government, the federal and the provincial governments, that what we have, that what we’ve recreated for ourselves, what we’ve regenerated in terms of our own governing structure, that that is really meaningful to our people and you can speak to people just on the street and they know when we talk about constitution rebuilding, we talk about recreating our government, we talk about just governance in general, people know what we’re talking about and I find that, ”

Ian Record:

“So that part of it’s taken on a life of its own, essentially.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely, yeah. And so, I mean, that’s a really positive outcome for us. And I wonder whether or not we would have been able to have that kind of an outcome if we weren’t involved, engaged in this particular negotiation with the government, but I do make that point that we may or may not reach a treaty. In fact, our American cousins tell us, ‘Why do you want to sign a treaty with the governments? They never live up to them, so why are you engaged in this?’ But for us, it’s been a really good process for our own people of engaging ourselves.”

Ian Record:

“In past conversations, you have pointed to the act of defining citizenship or more appropriately redefining citizenship as a critical first step in the Ktunaxa Nation forging a vibrant future of its own design. How so?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, I think that the, one of the key elements or one of our key pillars of course are our people, and our people embody our language and culture and you don’t have a choice what you’re going to be born as. Any of our people, when they’re born, we’re Ktunaxa, just as Italians are Italians and it doesn’t matter if they marry a Chinese [person], it doesn’t change them from being Italian. Well, same thing with us. And there’s been so much interference from government in terms of our own Aboriginal identity, Indigenous identity -- and I’m talking about all governments, not just in Canada -- that I think that one of the key elements of rebuilding nations is to take back ownership of the recognition of our own people. And I know that it creates difficulty because there’s a lot of, there’s very few pure blood as you would imagine, as you could say in this day and age just because of all the interaction that we’ve had with the rest of the world. But that doesn’t take away from someone who can trace their ancestry, if you can trace your ancestry to being Ktunaxa, then you’re accepted as Ktunaxa. I’ve mentioned before that our language and culture is very important and in the Ktunaxa language the word for our ancestors is '[Ktunaxa language]' and the root word of that '[Ktunaxa language]' comes from '[Ktunaxa language],' which is a root. You talk about the roots of a tree and any kind of a plant it’s '[Ktunaxa language]' and for, when you put those two words together '[Ktunaxa language],' meaning 'our roots.' And so if you can trace your ancestry to being Ktunaxa, then that’s who you are and you’re accepted as such. So that it’s not a matter of again the government interference saying that there are certain percentages or if you’re, like we had in the Indian Act. For a while, if you’re an Indian woman and you marry someone who’s not a status Indian, then you lose your status. That’s fine, that status was determined by the federal government to begin with, but it never ever changed the fact that that Indian woman is and always will be an Indian and so will her children.”

Ian Record:

“So has that taken some getting used to among some community members, ”

Sophie Pierre:

“Sure it has.”

Ian Record:

“, who have for so long relied on that blood quantum?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely, yeah. And I expect that it will affect probably all of our people in that way wherever there’s been government interference in terms of determining who the people are. So again it goes back to your original question, what is sovereignty? Sovereignty is being able to determine who your own people are and welcoming all people that are of your blood, whether they’re full blood or one-sixteenth. If they can trace their ancestry, that’s what that word means '[Ktunaxa language],' you can trace your ancestry, you can trace your roots to whatever nationality and I think that it would be the same if you’re English or German. If you can trace your roots, there’s sort of this Pan-Canadian or Pan-American, like what is that? They really should, everyone has roots from somewhere else other than the Indigenous people. We’re the ones that have roots here.”

Ian Record:

“And in some way doesn’t that entail at least some level of cultural engagement? So what you’re saying is you have to be able to trace your roots. It’s very hard to do that unless you’re participating in that culture, right?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Exactly, that’s right. Yes. Yeah, we’re going to have Ktunaxa people that probably will never become, will never come home, will never be part of our activity of our government, of our communities, simply because they don’t choose to. Maybe they’re part Irish and that’s the roots that, that’s the [Ktunaxa language] they’ve chosen to follow. That’s fine. What I’m saying is that when a person chooses to follow their Ktunaxa [Ktunaxa language], then we have a responsibility to that person, to that individual.”

Ian Record:

“The how of constitutional reform, of government reform is as important as the what. That’s been our experience at the Native Nations Institute and research we’ve done. What process has your nation employed to ensure that the governmental reform that you’re undertaking proceeds the way you envisioned and what have been the keys to that success thus far?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, I think that we’ve had the fortune, we’ve been fortunate to have the acquaintance of such people as Stephen Cornell and Joe Kalt and Manley Begay. I remember that when we first started talking about this that Stephen and Manley came and spent some time with our leaders, and it was really interesting because all of our leaders and particularly the older people who maybe didn’t speak English as well, but they were all saying the same thing and they could really connect with the discussions that we were having around the necessity of the definition of our governance being formalized if you will into a constitution. Like other Indigenous people, we come from an oral culture. So when we talk about and when we have a good understanding, and particularly when we use the Ktunaxa language, it’s all in an oral manner, but you take that to the next level and you start putting that down into a constitution and it makes sense to people when you do that.”

Ian Record:

“So if you can give us a little bit more specifics about the process that Ktunaxa Nation has employed to engage in governmental reform and what is really key to the success thus far, because it’s a very difficult process. It’s confronting a lot of colonial legacies that a lot of people would just as soon not confront.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely. The main activity that we’ve done is that all of our discussions have been open and these go back again to the negotiations that we have with the other two levels of government. We chose that ours would be called a citizen-led process. Unfortunately, some of the Indian nations in British Columbia that are involved in treaty go behind closed doors and it’s their lawyers that are negotiating and then they bring something back to the people later. We knew that that’s not what we wanted, that wouldn’t work for us. It might work for other people, but it wouldn’t work for us. So we started with a citizen-driven process right from day one and so it was that engagement of our citizens from the beginning. And I’ll tell you, that wasn’t easy because the first reaction we got was, ‘Yeah, right. You’re going to ask us a bunch of questions, but then it’s going to sit on a shelf somewhere. Our input is never meaningful, our input never gets into the final action,’ but I think that the, well, not I think, I know that our citizens are very pleased when they see their own thoughts, their ideas, they see themselves as we move forward in the final documents that are coming out that are reaching fruition now and people can see the input that they’ve had. And so then of course it’s more meaningful for them.”

Ian Record:

“The Ktunaxa Nation has made a concerted effort to get its young people heavily involved in governance and governmental reform. Why is this so critical?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Because they’re the ones that are going to live with the consequences and of course that underlies this whole thing -- is they’re the ones that are going to live with the consequences. I’m going to be long gone and it’s going to be the younger people that are going to have to put this into fruition for us and for their children and their grandchildren. But I think that how we’ve done that is maybe as important, it goes back again to when you engage people to actually make them feel that their engagement is worthwhile. So that it’s young people that we’ve had out there that have been leading the meetings, they’re the liaisons that go into the community, that sit at the kitchen tables and talk with people or go into Band meetings or make presentations at nation meetings. You don’t always have the old-timers like myself up there speaking. No, it’s, the presentations are made by the people that are actually out there gathering the information.”

Ian Record:

“And how have perhaps the older generations responded? Are they inspired by the eagerness of the youth?”

Sophie Pierre:

“I think as a whole, yes, and of course there’s always some old curmudgeon that sits somewhere thinking that, ‘These kids should be listening as opposed to talking,’ but I think that you learn by doing and I think that the majority of people recognize that.”

Ian Record:

“One of the great success stories of the Ktunaxa Nation is the St. Eugene Mission Resort, which I know you’re very proud of.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Yes.”

Ian Record:

“Can you tell us in a nutshell the story of St. Eugene and how what is now the resort and a major economic development engine for your people, how that story is emblematic of the Ktuxana Nation’s effort to reclaim their culture, their identity and their future?”

Sophie Pierre:

“You’re right, we are very, very proud of the St. Eugene Resort and because, I think the most important reason is that we chose to take something that was so negative in our past and turn it into something positive for our future. I say it that way because it really was a choice. When the residential school was shut down in 1970, the oblates, the priests who ran the school, the priests from the Catholic Church who ran the school, they turned over the property to the federal government with the understanding that the federal government would then turn it over to our tribal council. And when that was done, we were a bit unsure on what we were going to do. It’s a huge building and we could have turned it into like another school or health facility, some social-type program that would always be needing an infusion of cash; [we] chose instead to turn it into a business. And so we needed to have the approval of our people to do that and there were some people that told us that we should just knock it down. They said like that was such a horrible place, they suffered so much in that building that they wanted to see it just flattened, take it off the face of the earth. However, there were a greater number of people that understood what we were saying about turning it into something positive instead of knocking it down. So we made that choice rather than knocking it down to turn it around, and it was not easy and in fact it was very, very challenging. But we persevered and we were successful and we now have two other First Nations partners, Samson Cree Nation from Alberta and M’Chigeeng First Nation from Ontario, and it’s doing very well.”

Ian Record:

“So has that decision that you talked about, has that helped at least in some measure the community to begin healing from the experiences that took place there?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Very much so. I think a lot more so than if we had just knocked the building down. I think that actually seeing what it’s become and knowing that we did that ourselves, knowing that we made that decision and that choice to do that ourselves, I think that’s just been phenomenal and it really has had an impact. And what you see now is the younger generations refer to that as the resort. It’s only my generation that refers to it as the former school. It’s something positive and that’s what we wanted to do.”

Ian Record:

“So for younger generations and those to come it’s going to mean something a whole lot different then.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely, yeah. Yeah. For them it means a place to work, it means a place to go and recreate and it just means so much more and it’s so different from what it meant to us, to my generation.”

Ian Record:

“So you’ve been a leader for quite a long time, probably even longer than you were a leader in an elected capacity, I would imagine in my interactions with you. Pretend that I am a newly elected tribal leader who has been chosen to serve his nation for the first time. Drawing on your extensive experience as I’ve talked about, what advice would you share with me to help me empower my nation?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Talk to people, always just go around and meet with your citizens and talk with them. From elders, you’re going to learn so much from the elders, you’re going to learn from people who’ve served on council and you’re going to learn what people need when you talk to the younger generations so that’s what I, when I, the other piece of advice that I always give is that being elected is a privilege and it’s something that you have to, you are taking on a responsibility and it’s not, it’s not a position of power, it’s a position of serving your people. That’s what being elected means and you can only do that well if you know what it is your people need and assuming that your people need one thing when you haven’t gone out and talked to them about it is not a good thing to do.”

Ian Record:

“That’s interesting you mention this kind of axis between power and responsibility because we hear that so often among tribal leaders of nations who are really breaking away as we like to say, who are really finding success with their efforts to rebuild their nations in a way that they see fit and not perhaps a way that outsiders see fit -- we see that axis kind of, that axis pivoting on this issue of clearly defining your roles and responsibilities and that the conversation around leaders, it’s about responsibility and not so much power is when those roles are clearly defined. When they’re not clearly defined, it’s very hard to get away from the power issue because there’s nothing to keep you from overstepping your bounds.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Yeah, exactly and I think that that’s where it’s the process that we’ve gone through just in this last little while, because things are changing for us, and we are starting to see more financial resources coming into our communities for example, financial resources which are not grants from government, these are our own revenues, our own source of revenues, and it’s imperative that we’re ready for that and that those decisions have been made on how those resources are going to be shared among everyone before it actually starts to flow and how everybody is going to be able to benefit from it. So having that kind of responsibility and understanding that kind of responsibility as opposed to seeing it as power and using it over people -- we’ve seen the results of that. I don’t want to take any community, but you’ve seen the results of that. It’s not a good place to be.”

Ian Record:

“You kind of stole my thunder with this next question already on the advice question I asked you, but one of the things you and I have talked about in the past is this issue of effective leaders not just being decision-makers but effective leaders being good educators and good listeners and really what we’re talking about, we’ve talked about is this issue of citizen engagement, that it’s not enough just to engage your citizens come election time, but that to be an effective, empowered leader you have to be engaging your citizens all the time and that comes in the form of one-on-one personal interaction to getting the word out on the internet, whatever it might be. Can you just discuss your perspective on this issue of leaders as educators, leaders as listeners and how that plays out in your community?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, I think that it’s important that when a person is in a position of leadership that you also recognize the, not just the responsibility but the onus that is on you to ensure that people feel confident that you’re going to be able to represent what they need both within the community and also on the outside. So I think that that’s another very important part of leadership is to be able to go into the wider society and talk about the issues that are important to you like say some of the land development that’s going on and I would think [is] affecting all Indian nations. I was listening to that, the presentation just a little while ago from Ak-Chin and how they’re taking on the development that’s going on around them and getting, and their leadership made sure that the community that has infringed all the way around them is aware that, what the outside community is doing is going to affect life in their community and I think that that is a very important part of leadership. So there’s the leadership within the community and you’re absolutely right about, that you need to have input and you need to be able to listen to everybody’s point of view. And half the time, they’re not going to agree with what you’ve said and that’s okay. You engage in those discussions and eventually come to an agreement where that everybody can live with. So you engage your own citizens internally, but then you also have to engage the people that live around you and you have to do it in such a way that it’s respectful, but it’s also forceful so that people will listen.”

Ian Record:

“So really what you’re talking about in terms of leaders as educator,s it’s not just a challenge to educate your own citizens but there’s this kind of constant challenge of having to educate those people outside of your nation that are making decisions that are going to impact your nation’s future.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely, yes. And I think that that is becoming more and more a very important part of leadership. I think it probably always has been but it has not really, it hasn’t played as prominent a role, but I think that nowadays you cannot be a leader in your community without being able to communicate with the wider society about what it is that your nation or your community is involved in, and I think that one of the very important messages to make, too, is how much our communities are part of the larger community so to speak in terms of, even just in terms of economics when you figure how much money is actually spent in the local town of Cranbrook, for example, by people from my community and how much the businesses rely on that and what would happen if we were to suddenly not support Cranbrook business anymore. I think that it’s those, that kind of being real players in the whole life of the region. I think it’s very important.”

Ian Record:

“One of your neighboring nations, the Osoyoos Indian Band, shares this, at least their leadership shares this perspective about the importance of their nation going out and educating again these outside decision-makers whose decisions impact the nation. They made a concerted effort to do that, particularly around economic development as you mentioned and the incredible ripple effect that takes place when economic development takes place in Aboriginal communities.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely. That’s the point that I always make is that when we’ve got any financial resources coming into our community, we don’t squirrel it away in some Swiss bank. We go and spend it in the local community so it’s, it makes a big difference.”

Ian Record:

“We call it the 'Walmart effect' down here in the United States.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Yeah.”

Ian Record:

“It was interesting, in preparing for this interview I happened to Google your name and one of the first links that popped up was YouTube, and I had occasion to review a video that was recently posted on YouTube about the Farnham Blockade. Can you tell us a bit about the background to that story and why you felt it so important to take part in the blockade?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, it’s a major development, major tourism development on a very fragile glacier and the whole development itself from the get-go has been of great concern to us because we see that it’s, the development is of such a magnitude that it’s going to have impacts not only on the environment, which it’ll have a very detrimental impact, but on the wildlife and on the people that live there. It’s going to affect us in every way possible. So we’ve always been concerned about that and we have not been able to find any reason from the studies that have been done and everything that has been given to us, we haven’t been able to find any reason to support that level of development. And the provincial government has been kind of interesting in the position that they’ve taken here, because on the one hand they say that people in the local region should be the ones to make a decision because they’re the ones that are going to be impacted by the development. But on the other hand, they do these kind of, it’s almost underhanded actions that they take, where we found out in terms of the Farnham Incident, we found out that the provincial, one of the provincial ministries had actually transferred a license that they had given to a non-profit, Olympic ski organization that trains Olympic skiers, they had transferred that tenure from this non-profit to the development, to the profit-oriented group and in a very major way they transferred this tenure and hadn’t told anyone. And so when my colleagues brought this up, the response from the ministry was, ‘Oops, I guess we forgot to tell you.’ It was just very, very irresponsible kind of actions. So I think that the government really need, the provincial government in this case, they really need to put their own actions in what they say that they’re going to do. If it’s important for local citizens to make the decisions about the areas that they live in, then they should be allowed to do so and not have the provincial government step in and decide what’s going to be in our best interest. I think we’re beyond those days, I would certainly hope that we are anyway.”

Ian Record:

“So what do you see for the future of this issue?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Well, right now I think that we’re going to have to continue to fight it, quite frankly. I don’t see a whole lot of support coming from the province, I don’t see a lot of leadership coming from the province and the local people, I think at the last count and they do it fairly regularly, it’s like 85 or 90 percent opposition by our local citizens and I’m not talking just about the Aboriginal people of which our tribal council has had a formal position that we are very concerned with the proposed development because of its size. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist, as they say, to figure out that our environment is in real dire straits and you take a look at that poor glacier. It is just ravaged and they’re talking about building a resort on it so that people can ski on it in the summertime. At some point, rational thought has got to start kicking in.”

Ian Record:

“Do you feel your nation and others have a leadership role to play in that regard?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Oh, absolutely, and we are very, we very much step up to the plate with that one.”

Ian Record:

“What do you see for the future of First Nations in Canada when it comes to self-determination and specifically governance?”

Sophie Pierre:

“That’s an interesting question because the, on the one hand, our Canadian government would probably say that there’s a very large, there’s a big move towards self-determination and governance. In fact, they’ve got programs called 'Self-Determination' and 'Self-Governance.' And of course that is the exact opposite of self-determination and self-governance. However, I think that there’s a couple things that are at play that will support self-determination and self-governance. In British Columbia, we have the treaty process, which some of us are taking advantage of in that way to re-establish our own governments but then there’s, we’ve also been fortunate in some of the court decisions that have been made, the legal cases that have been made that have led the government to actually vacate areas that they assumed that they had some say, and so we’ve been able to enforce Aboriginal title, Aboriginal rights in that way so yeah, I think that that’s, that’s been sort of an interesting outcome of some of the court decisions.”

Ian Record:

“So what about your nation specifically? You mentioned earlier on in the interview about...that strategic planning has been a key for you as you’ve moved towards governmental reform for instance, you’ve got a strategic plan in place or a strategic vision of where you want to head. What does the future look like for Ktunaxa Nation and how is the nation today working to get there?”

Sophie Pierre:

“It’s our mission statement. I’ve mentioned that it covers all aspects, it covers the Four Pillars that are the Bible for us, so to speak. And so for our organizations, our governments, our elected leadership, we know that that is our path and so if the government comes along with a new program, we measure it by our mission statement. Does it fit with our mission? If it doesn’t, carry on, move on to somebody else, leave us alone. We have our path, we’ve set our sights on what our nation is going to look like and it’s going to be the embodiment of that mission statement and if other people’s actions don’t fit in with that, then we don’t become involved.”

Ian Record:

“So what you’re saying is that this mission statement, which is essentially as you’re talking about your strategic plan, it’s where you want to head long-term.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Yes.”

Ian Record:

“It gives you a basis upon which to decide matters that are before you, day to day.”

Sophie Pierre:

“Exactly, yes.”

Ian Record:

“And that essentially, does that not really empower you as a leader?”

Sophie Pierre:

“Absolutely and well, yeah, it’s actually, it makes it a lot easier I think to start, when you start juggling things and particularly as we’ve come to this place where we’re at and we’ve had to depend so much on other governments to...and other sources of resources coming into our communities, whether they’re financial resources or whatever to keep our communities moving, we’ve always had to react to somebody else’s agenda and it’s been so empowering to say, ‘We don’t have to do that anymore. We know what it is we want: strong, healthy citizens speaking our language and practicing our culture in our homelands in a self-governing manner and looking after our own lands and resources.’ It covers all those areas and so if something comes along that doesn’t fit in there, then like I said, I don’t have to worry about it. As chief, I don’t have to worry about it. And the next administration, they will find that it’s going to be a lot simpler just to follow that plan.”

Ian Record:

“Well, Sophie, I’d like to thank you very much for taking the time to join us today. I’ve certainly learned a great deal and I’m sure our audience has as well. That’s all for today’s program of Leading Native Nations, produced by the Native Nations Institute and Arizona Public Media at the University of Arizona. To learn more about this program and Sophie Pierre and the Ktunaxa Nation, please visit the Native Nations Institute’s website at www.nni.arizona.edu. Thank you for joining us. Copyright 2008. Arizona Board of Regents."