Indigenous Governance Database

land acquisition

Landback: The Return of Upper Sioux Agency State Park to the Upper Sioux Community

After decades of campaigning by Upper Sioux Indian Community Chairman Kevin Jensvold, the State of Minnesota finally returned the land formerly known as Upper Sioux Agency State Park to its rightful Dakota stewards in March 2024. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Director of Tribal…

University of Arizona Land Grant Project

Tracking the History of Land-Grant Enrichment at the University of ArizonaAn interactive story map built by the James E. Rogers College of Law Land-Grant Project Team, the goal of the University of Arizona Land-Grant Project is two-fold:(1) to research, share, and begin to understand how the…

Indigenous Land Acknowledgment

Native Governance Center co-hosted an Indigenous land acknowledgment event with the Lower Phalen Creek Project on Indigenous Peoples’ Day 2019 (October 14). The event featured the following talented panelists: Dr. Kate Beane (Flandreau Santee Dakota and Muskogee Creek) Mary Lyons (Leech Lake…

Considerations for Federal and State Landback

This policy brief showcases how geographic information system (GIS) techniques can be used to identify public and/or protected land in relation to current and historic reservation boundaries, and presents maps showcasing the scope of landback opportunities. These lands include federal- or state-…

Indigenous Land Management in the United States: Context, Cases, Lessons

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is seeking ways to support First Nations’ economic development. Among its concerns are the status and management of First Nations’ lands. The Indian Act, bureaucratic processes, the capacities of First Nations themselves, and other factors currently limit the…

Yakama Nation Land Enterprise

In an effort to consolidate, regulate, and control Indian land holdings, the financially self-sustaining Yakama Nation Land Enterprise has successfully acquired more than 90% of all the fee lands within the Nation’s closed area — lands which were previously highly "checker-boarded." The Enterprise’…

Chilkoot Tlingit "Nation Building"

Excluded by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, the Chilkoot Tlingit are engaged in a process of nation-building. The process began in 1990 with the revival of their dormant tribal government, the Chilkoot Indian Association (CIA). From this institutional foundation, the 480-member CIA…

Grand Traverse Band's Land Claims Distribution Trust Fund

After 26 years of negotiation with the US government over how monies from a land claims settlement would be distributed, the Band assumed financial control over the settlement by creating a Trust Fund system that provides annual payments in perpetuity to Band elders for supplementing their social…

Honoring Nations: Cedric Kuwaninvaya: The Hopi Land Team

Former Chairman of the Hopi Land Team Cedric Kuwaninvaya presents an overview of the tribal subcommittee's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Pat Cornelius: Oneida Nation Farms

Manager of the Oneida Nation Farms Pat Cornelius presents an overview of the organization's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Erma Vizenor: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change: The White Earth Nation Story

White Earth Nation Chairwoman Erma Vizenor discusses some of the historical factors that eventually compelled her and her nation to undertake constitutional reform, and the issues her nation has encountered as they work to ratify a new constitution and governance system.

Cast-off State Parks Thrive Under Tribal Control, But Not Without Some Struggle

Rick Geisler, manager of Wah-Sha-She Park in Osage County, stands on the shore of Hula Lake. When budget cuts led the Oklahoma tourism department to find new homes for seven state parks in 2011, two of them went to Native American tribes. Both are open and doing well, but each has faced its own…

CDFI Fund Awards Indian Land Capital Company its Third $750K Award

For the third year in a row, Indian Land Capital Company (ILCC), an American Indian-owned and -managed Native Community Development Financial Institution (Native CDFI) and leader in the tribal land financing and acquisition movement, has received the highest tier financial award, $750,000, from the…

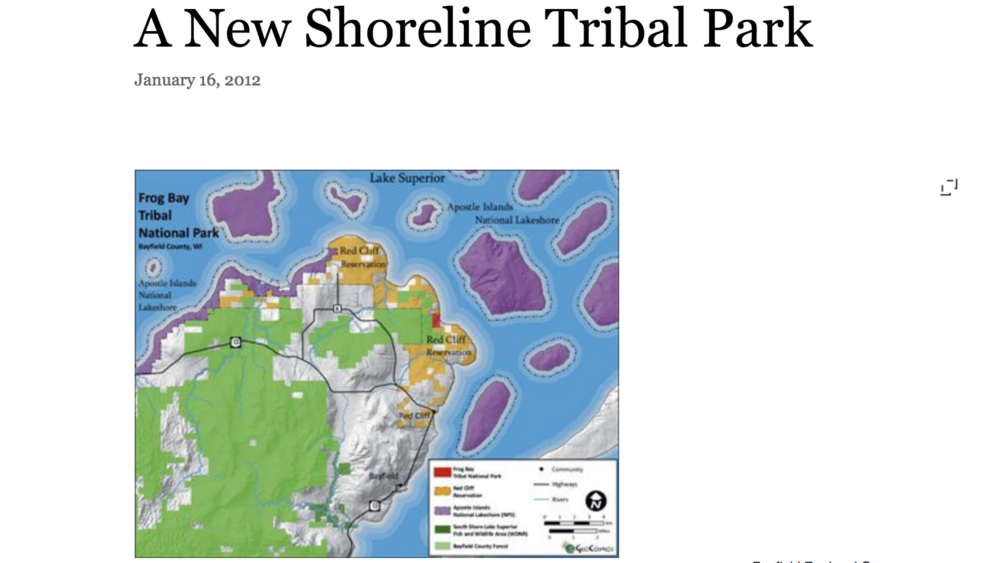

A New Shoreline Tribal Park

The 87 acres at Frog Bay in Wisconsin recently designated as a park offer views of five Apostle Islands, pristine sandy beaches at the top of Bayfield Peninsula and a rare opportunity for the public to visit tribally owned and protected lands. Frog Bay Tribal National Park was created when the Red…

Legend Lake: A Talking Circle

The documentary video recounts the saga of Legend Lake, a beautiful 5,160 acre lake development, formed by joining 9 smaller lakes in the Menominee Indian Reservation (with the same boundaries as Menominee County) in northern Wisconsin whose shore land was subdivided and sold mostly to non-…

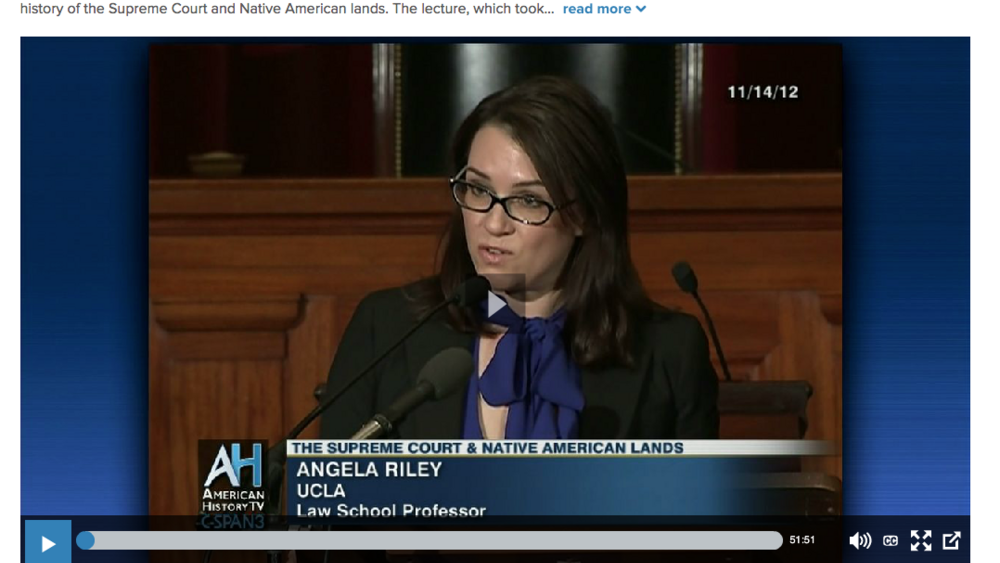

Native American Lands and the Supreme Court

Tribal judge and legal scholar Angela Riley (Citizen Potawatomi) spoke in the U.S. Supreme Court chamber about the history of the Supreme Court and Native American lands. The lecture was one in a series hosted by the Supreme Court Historical Society on the Constitution, the Supreme Court, and…

Managing Land, Governing for the Future: Finding the Path Forward for Membertou

This in-depth, interview-based study was commissioned by Membertou Chief and Council and the Membertou Governance Committee, and funded by the Atlantic Aboriginal Economic Development Integrated Research Program to investigate methods by which Membertou First Nation can further increase its…

Best Practices Case Study (Territorial Integrity): Yakama Nation

The Yakama Nation is located in central Washington State. Their struggles with land loss began over 150 years ago when, in 1855, the federal government pressured the Yakama to cede by treaty more than ten million acres of their ancestral homelands. In the latter half of the 1800s and early 1900s,…