Indigenous Governance Database

land management

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation: Distribution of Authority Excerpt

ARTICLE II - LAND Section 1. Recognition. We, the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, do not accept a diminishing of our sovereign status as a nation and of our vested or inherent rights by the act of adopting this constitution. Section 2. The Tribal Council shall establish a standing Committee vested…

Indigenous Land Management in the United States: Context, Cases, Lessons

The Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is seeking ways to support First Nations’ economic development. Among its concerns are the status and management of First Nations’ lands. The Indian Act, bureaucratic processes, the capacities of First Nations themselves, and other factors currently limit the…

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Monitors Program

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is located on 2.3 million acres of land in the central regions of North and South Dakota. Land issues rose to the forefront of tribal concerns after events such as allotment, lands flooding after the Army Corps of Engineers built a series of dams adjacent to the Tribe…

Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Land Title and Records Office

With the ultimate goal of seeing a time when Native people and nations once again own and manage the land within the boundaries of every reservation as well as those lands that are culturally important to them beyond reservations, the Tribal Land Title and Records Office keeps all records and…

Miccosukee Tribe Section 404 Permitting Program

The reservation lands of the Miccosukee Tribe lie largely within the Everglades National Park. Development on these lands is subject to elaborate regulations by a host of federal agencies that hindered development and other uses of their lands by the Miccosukee people, including the building of…

Honoring Nations: Cedric Kuwaninvaya: The Hopi Land Team

Former Chairman of the Hopi Land Team Cedric Kuwaninvaya presents an overview of the tribal subcommittee's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Tim Mentz and Loretta Stone: Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Monitors Program

Tim Mentz and Loretta Stone of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Monitors Program present an overview of the program's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Kristi Coker-Bias and Allen Pemberton: The Citizen Potawatomi Community Development Corporation and the Red Lake Walleye Recovery Program (Q&A)

Honoring Nations symposium presenters Kristi Coker-Bias and Allen Pemberton field questions from the audience about the Citizen Potawatomi Community Development Corporation and the Red Lake Walleye Recovery Program.

Catalyx and Ramona Tribe Start Work on 100% Off-Grid Renewable Energy Eco Tourism Resort

Catalyx, Inc. has been contracted to be the technology provider and will team with the Ramona Band of the Cahuilla Indian Tribe to develop the Tribe's Eco-Tourism resort near Anza, Calif. The first of its kind, the Ramona Band of Cahuilla Mission Native Americans' resort is designed as a 100% off-…

People Belong to the Land; Land Doesn't Belong to the People

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) does not recognize the right of indigenous nations to own land outside the laws and rules of national governments. According to international historical doctrines of discovery, Indigenous Peoples, non-Christian nations,…

Cast-off State Parks Thrive Under Tribal Control, But Not Without Some Struggle

Rick Geisler, manager of Wah-Sha-She Park in Osage County, stands on the shore of Hula Lake. When budget cuts led the Oklahoma tourism department to find new homes for seven state parks in 2011, two of them went to Native American tribes. Both are open and doing well, but each has faced its own…

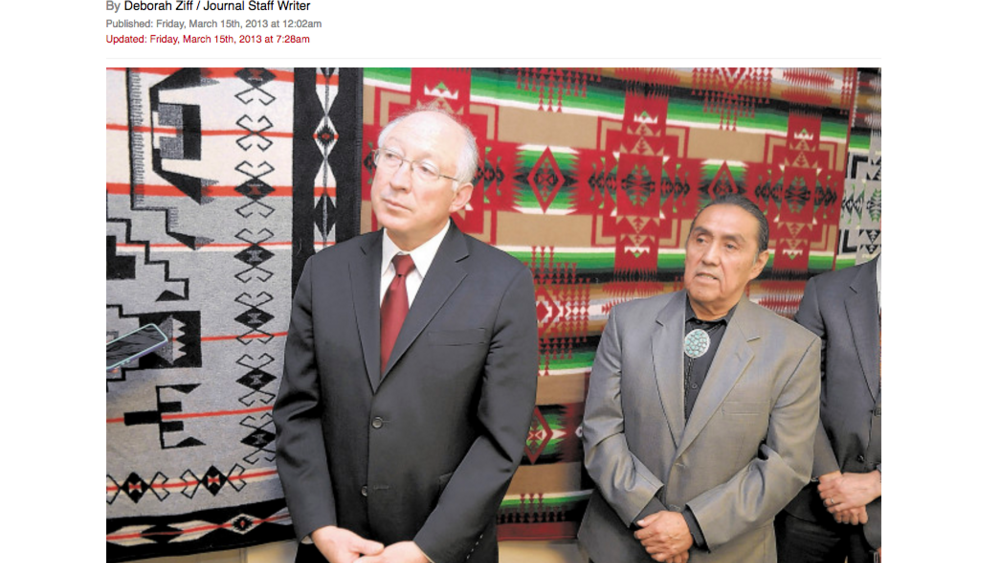

A 'historic day' at pueblo

Secretary of Interior Ken Salazar called it a “historic day” as he signed regulations at Sandia Pueblo on Thursday morning that will allow the tribe to lease land without federal approval. The pueblo is only the second tribe in the country to take advantage of a law, called the HEARTH Act (Helping…

Tribal Land Leasing: Opportunities Presented by the HEARTH Act and Amended 162 Leasing Regulations

This NCAI webinar discussed amendments to the Department of the Interior's 162 leasing regulations as well as practical issues for tribes to consider when seeking to take advantage of the HEARTH Act (Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership Act of 2012)...

Exercising Sovereignty and Expanding Economic Opportunity Through Tribal Land Management

While the United States faces one of the most significant housing crises in the nation’s history, many forget that Indian housing has been in crisis for generations. This report seeks to take some important steps toward a future where safe, affordable, and decent housing is available to Native…

Managing Land, Governing for the Future: Finding the Path Forward for Membertou

This in-depth, interview-based study was commissioned by Membertou Chief and Council and the Membertou Governance Committee, and funded by the Atlantic Aboriginal Economic Development Integrated Research Program to investigate methods by which Membertou First Nation can further increase its…

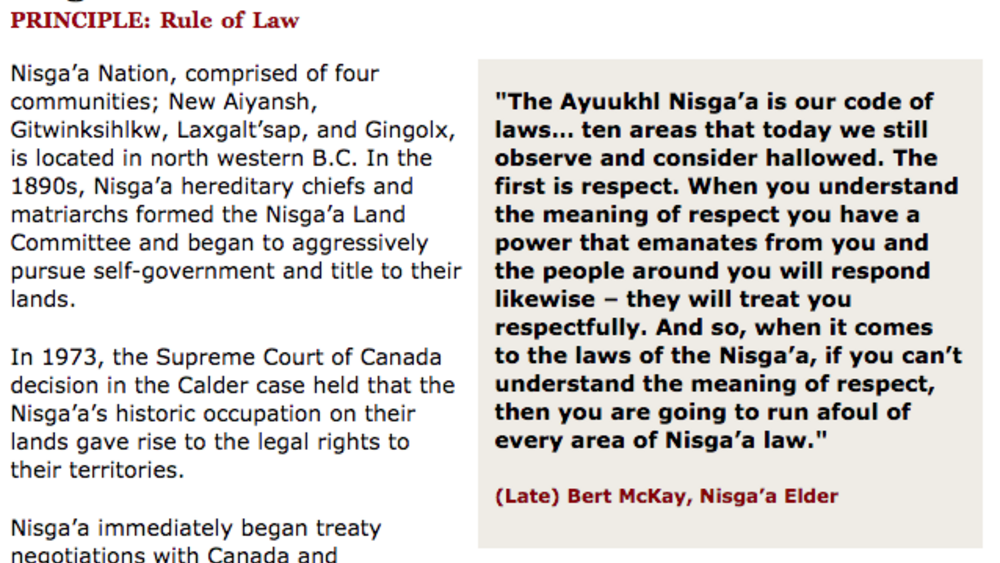

Best Practices Case Study (Rule of Law): Nisga'a Nation

Nisga'a Nation, comprised of four communities; New Aiyansh, Gitwinksihlkw, Laxgalt'sap, and Gingolx, is located in northwestern B.C. In the 1890s, Nisga'a hereditary chiefs and matriarchs formed the Nisga'a Land Committee and began to aggressively pursue self-government and title to their lands.…