Indigenous Governance Database

language revitalization

Mille Lacs Ojibwe Language Program

Created in 1995, this tribally funded program serves 350 students (from toddlers to teenagers) and uses elder-youth interaction, song books, and comic books to teach the Ojibwe language. In addition, the Program broadcasts language classes to local public schools in an effort to teach the Ojibwe…

Chickaloon Village: Ya Ne Dah Ah School

Dedicated to giving community youth the skills necessary for functioning in a modern world while retaining and facilitating traditional knowledge and practices, the Ya Ne Dah Ah is Alaska’s only tribally owned and operated full-time primary school and day care facility. Located in a one-room…

Makah Cultural Education and Revitalization Program

The Cultural Education and Revitalization Program serves as the hub of the community and stewards of a world class museum collection. Keen efforts and awareness demonstrated by staff and community members make this Center unique. Programs are truly guided by the needs of the Nation and its citizens…

Akwesasne Freedom School

In 1979, the Akwesasne Freedom School took form out of the Mohawk struggle for self-determination and self-government. It is characterized by a deep commitment to the maintenance of Mohawk identity. Students in this pre-kindergarten through 8th-grade language immersion school begin and end each…

Cherokee Language Revitalization Project

In 2002, the Cherokee Nation carried out a survey of its population and found no fluent Cherokee speakers under the age of 40. The Cherokee Principal Chief declared a "state of emergency," and the Nation acted accordingly. With great focus and determination, it launched a multi-faceted initiative…

Cherokee National Youth Choir

The Youth Choir presents an innovative approach to promoting and encouraging the use of the endangered Cherokee language among its youth while also instilling Cherokee cultural pride. The award-winning choir — comprised of 40 young Cherokee ambassadors — has performed in venues across the US,…

Good Native Governance Plenary 3: Innovative Research in Education: Educating Tomorrow's Tribal Leaders

UCLA School of Law "Good Native Governance" conference presenters, panelists and participants Tiffany S. Lee, Sheilah E. Nicholas, and Tarajean Yazzie-Mintz focus on the process of educating tribal leaders, youth, and entire communities through relationships and collaborations. This video…

Jim Gray and Patricia Riggs: Citizen Engagement: The Key to Establishing and Sustaining Good Governance (Q&A)

Presenters Jim Gray and Patricia Riggs field questions from audience members about the approaches their nations took and are taking to engage their citizens and seed community-based, lasting change. In addition, session moderator Ian Record offers a quick overview of some effective citizen…

Cherokee National Youth Choir - Video

This video -- produced by the Cherokee Nation Education Department -- is a sample reel of the Cherokee National Youth Choir, an innovative approach to promoting and encouraging the use of the endangered Cherokee language among its youth while also instilling Cherokee cultural pride. The award-…

John Petoskey: The Central Role of Justice Systems in Native Nation Building

John Petoskey, citizen and longtime general counsel of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (GTB), discusses the key role that justice systems play in Native nation building, and provides an overview of how GTB's distinct history led it to develop a new constitution and system of…

Honoring Nations: JoAnn Chase: Cultural Affairs

JoAnn Chase reports back to her fellow Honoring Nations sympoisum participants about the consensus she and her fellow cultural affairs breakout session participants reached concerning the need for Native nations to fully integrate culture into how they govern, and also to ensure that their…

Honoring Nations: Dusty Delso: Cherokee Language Revitalization Project

Dusty Delso presents an overview of the Cherokee Language Revitalization Project to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: James Ransom and Elvera Sargent: The Akwesasne Freedom School

Elvera Sargent and James Ransom from the Sain Regis Mohawk Tribe present an overview of the Akwesasne Freedom School to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Elvera Sargent: The Akwesasne Freedom School

Elvera Sargent discusses the Akwesasne Freedom School and the role it plays in the cultural identity of each generation that goes through the curriculum.

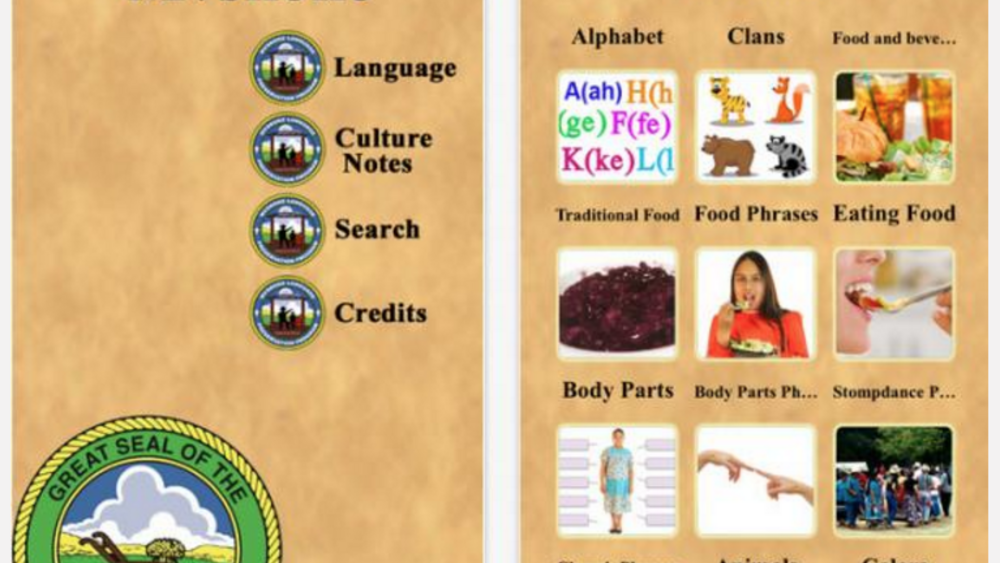

Muscogee (Creek) Nation Launches App to Help Preserve Language

In an effort to preserve the Muscogee (Creek) Nation language, the nation has developed a mobile app as a way for citizens to learn the language more easily. The Mvskoke (the traditional spelling of Muscogee) Language App is available free in the Apple store for iPhones and iPads, as well the…

Chickasaw Nation: The Fight to Save a Dying Native American Language

A 50,000-year-old indigenous Native American tribe that has weathered the conquistadors, numerous wars with the Europeans, the American Revolution and the Civil War is now fighting to preserve its language and culture by embracing modern technology. There are 6,000 languages spoken in the world…

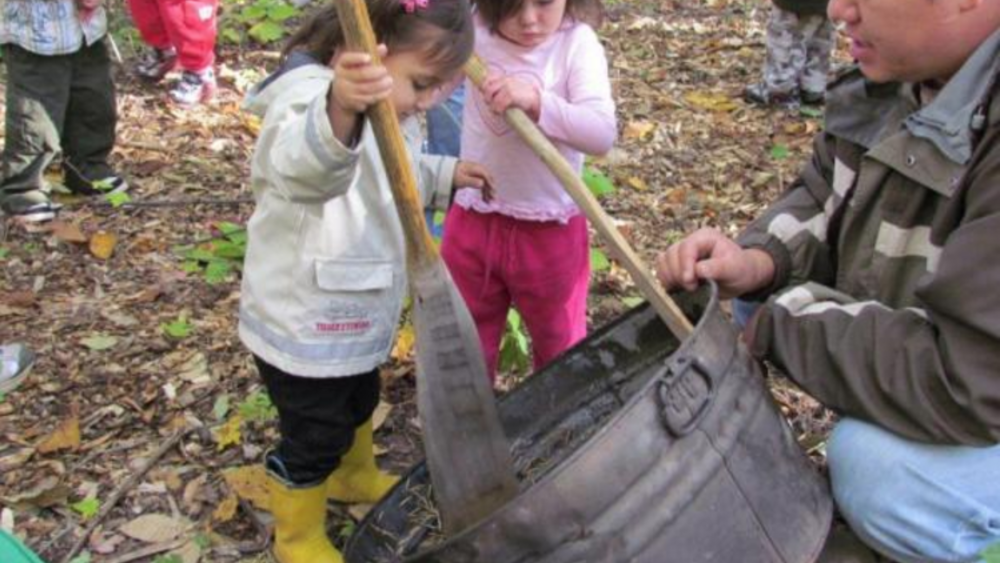

Preserving Culture: 6 Early Childhood Language Immersion Programs

Language immersion schools have proved to be enormously beneficial for young learners’ academics. To quote Dr. Janine Pease-Pretty on Top, Crow, founding president of Little Big Horn College, “Solid data from the Navajo, Blackfeet and Assiniboine immersion schools experience indicates that the…

Teaching the Whole Child: Language Immersion and Student Achievement

As Congress considers two bills to support Native American language immersion, including the Native Language Immersion Student Achievement Act, it is time to take stock. What does research say about the impact of Native-language immersion on Native students’ academic achievement? We now have 30…

'We are getting stronger'

An economic, political and cultural renaissance is underway throughout Indian Country in the United States. It’s been going on for nearly a quarter-century. Whereas in the 1980s, economic growth on Indian reservations lagged far behind the rate of the U.S. economy, through the booming 1990s and the…

Sleeping Language Waking Up Thanks to Wampanoag Reclamation Project

It’s been more than 300 years since Wampanoag was the primary spoken language in Cape Cod. But, if Wampanoag tribal members keep their current pace, that may not be true for much longer. Tribal members have been signing up for classes with the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project while families…