Indigenous Governance Database

sovereignty

Indian Country must put more effort in public relations

While sipping my morning coffee I began reading a White House document titled “2014 Native Youth Report.” As with every other tribal member, I am aware of the long-standing socio-economic quagmire we have been enduring. The fact that we are still alive and well is short of miraculous and thought…

Arizona tribe set to prosecute first non-Indian under a new law

Tribal police chief Michael Valenzuela drove through darkened desert streets, turned into a Circle K convenience store and pointed to the spot beyond the reservation line where his officers used to take the non-Indian men who battered Indian women. “We would literally drive them to the end of the…

The Bay Mills Case: An Opportunity for Native Nations

On May 27th, the U.S. Supreme Court finally handed down its decision in the Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community case. The good news for Native nations is that the Court upheld the doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity, opting not to carry out any of the doomsday scenarios many suggested could…

Klamath Agreements Strengthen Tribal Sovereignty

From time immemorial, salmon, steelhead and other fish runs have sustained the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin Paiute members of the Klamath Tribes. It has been more than 100 years, however, since our tribal members have seen salmon and steelhead migrate home to the Upper Klamath Basin, or had an…

Good Data Leads to Good Sovereignty

The lack of good data about U.S. American Indian and Alaska Native populations hinders tribes’ development activities, but it also highlights a space for sovereign action. In coming years, tribes will no doubt continue to advocate for better national data and at the same time increasingly implement…

Eastern Band of Cherokee Replenishes Iconic White-Tailed Deer on Its Lands

The Eastern Band of Cherokee, deprived for centuries of the white-tailed deer that symbolizes their culture, are in the process of getting their icon back. Though deer are considered almost a pest in many parts, devouring gardens and proliferating, the Cherokee themselves, who have cherished the…

Professor Breaks Down Sovereignty and Explains its Significance

Sovereignty is one of those terms we toss around without much thought. It is an important word within contemporary American Indian discussions. The term itself draws from legal, cultural, political, and historical traditions, and these traditions are connected to both European as well as Indigenous…

Disenrollment Demands Serious Attention by All Sovereign Nations

For most people, their sense of who they are–their identity–is at least partially defined from connection to others and to a community. When individuals are forced to sever those connections, the consequences can be devastating. Unfortunately, all too often in tribal disenrollment conflicts–like…

Embrace Our Sovereignty or Continue the Genocide?

“The most consistent theme in the descriptions penned about the New World was amazement at the Indians’ personal liberty, in particular their freedom from rulers and from social classes based on ownership of property. For the first time the French and the British became aware of the possibility of…

Robert F. Kennedy's Legacy with First Americans

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s address to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) in Bismarck, North Dakota. I was in high school then. My memories are that of tribal leaders who came together from throughout the nation to discuss key issues of…

Harvard Project Names 18 Semifinalists for Honoring Nations Awards

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development recognizes exemplary tribal government initiatives and facilitates the sharing of best practices through its Honoring Nations awards program. On March 3, the Harvard Project announced its selection of 18 semi-finalists for the 2014…

Winona LaDuke: Keep USDA Out of Our Kitchens

Native American author, educator, activist, mother and grandmother Winona LaDuke, Anishinaabekwe, is calling on tribes to relocalize food and energy production as a means of both reducing CO2 emissions and of asserting tribes' inherent right to live in accordance with their own precepts of the…

Yakama Nation Fights For Restored Authority

January 17, 2014 was a big day for the Yakama Nation tribe. On that day, Washington governor Jay Inslee signed a proclamation returning almost all civil and criminal authorities over to tribal members on the eastern Washington reservation. The next step is federal approval before the proclamation…

Will the Supreme Court Use Bay Mills Case to Blow Up Tribal Sovereignty?

As regular visitors to this site and other Indian country media outlets no doubt have seen in recent weeks, Native nation leaders, tribal attorneys, and federal Indian law practitioners alike are gravely concerned about a case currently pending before the Supreme Court: State of Michigan v. Bay…

How to Protect Tribal Lands From Our Deadliest Enemies

In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court dealt a severe below to Indian sovereignty when it decided Nevada v. Hicks, suggesting to states and counties that when their cops are investigating off-reservation crimes, they need not obtain tribal court warrants to conduct searches or arrests on tribal land. The…

Servants of the People

Traditionally, this title was an honor bestowed on those distinguished both by willingness to serve and effectiveness in doing so. This was our concept – unique throughout the world but one with such a strong sense of rightness that many would claim it for their own. Of course, claims and reality…

How Tribes Can Prepare for Tribal Sovereignty Blow From Supreme Court

In the first part of this two-part series, we provided a short history of the upcoming U.S. Supreme Court case State of Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Community, discussed its relevance to the sustainability of the legal doctrine of tribal sovereign immunity, and detailed two potential outcomes of…

Wisdom From Mel: It's Okay to Not Know Everything

Mel Tonasket was not formally educated but he had lobbied and negotiated with Congressman and Senators. When Mel was in Washington D.C. he heard the fancy words from the Solicitors office. He was determined to fight for tribes and not let the “Suyapees” (Anglos) get the best of us — so when he…

The Bay Mills Buck Stops With NIGC

With a case of potentially catastrophic consequence for Indian country now pending before the U.S. Supreme Court, all of the players who can possibly prevent the disaster are either sitting on their hands or pointing fingers. The National Indian Gaming Commission has failed to act, citing a…

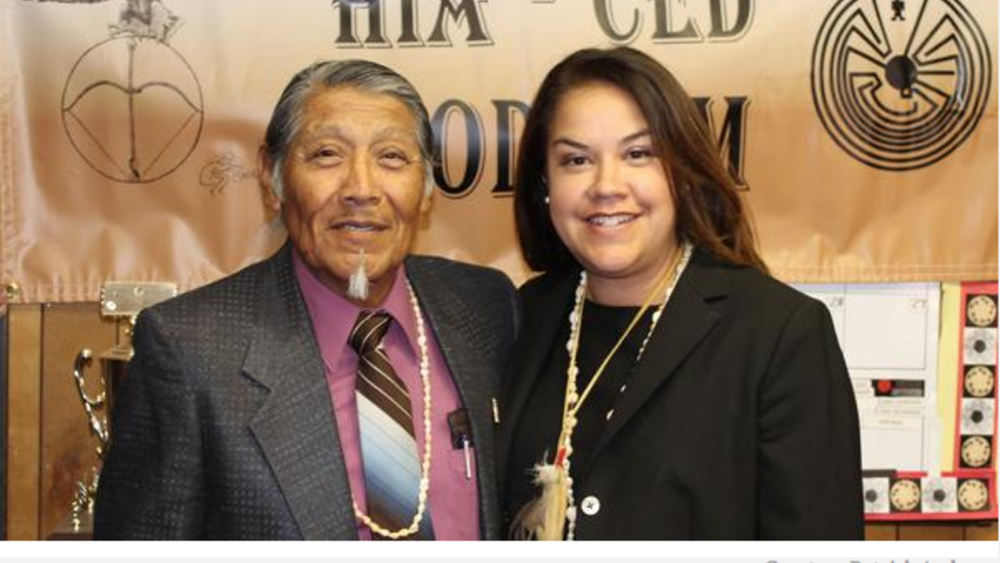

Extinct No More: Hia-Ced O'odham Officially Join Tohono O'odham Nation

After 33 years of hard work to right the past, the Hia-Ced O’odham, once thought to be extinct, can finally say they belong as part of the Tohono O’odham Nation. On June 12, the Hia-Ced O’odham District officials were sworn-in and the Hia-Ced District was officially recognized as the 12th district…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 8

- 9

- 10

- …

- Last page