Indigenous Governance Database

National

Suzan Shown Harjo: Nobody Gives Us Sovereignty: Busting Stereotypes and Walking the Walk

The first-ever speaker in the Vine Deloria, Jr. Distinguished Indigenous Scholars Series, Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne/Hodulgee Muscogee) shares her personal perspective on the life and legacy of the late Vine Deloria, Jr., and provides an overview of her work protecting sacred places and…

Honoring Nations: Joseph Singer: Sovereignty Today

Harvard Professor Joseph Singer makes a compelling case that Native nations' best defense of sovereignty is their effective exercise of it, and stresses the importance of educating the general public -- particularly young people -- about what tribal sovereignty is and means.

Joseph P. Kalt: Sovereign Immunity: Walking the Walk of a Sovereign Nation

Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Co-Director Joseph Kalt discusses what sovereign immunity is and what it means to waive it, and share some smart strategies that real governments and nations use to waive sovereign immunity for the purposes of facilitating community and…

Frank Pommersheim: A Key Constitutional Issue: Dispute Resolution (Q&A)

University of South Dakota Professor of Law Frank Pommersheim fields audience questions about the importance of civic engagement to constitutional reform, removing the Secretary of Interior Approval clause from tribal constitutions, and other important topics.

Native Nation Building TV: FOX News Segment on Native Nation Building

Joan Timeche, Stephen Cornell and Ian Record with the Native Nations Institute at The University of Arizona discuss the "Native Nation Building" television and radio series and the research findings at heart of the series in a televised interview in January 2007.This video resource is featured on…

How Can Tribes Relate to Off-Reservation Citizens Better? Study Aims to Help

How do you define “home?” “Home is where one starts from” is one explanation, while another states, “Our feet may leave home, but not our hearts.” Where you call home is especially important to Native Americans who have left the familiarity of where they grew up among fellow tribal members and…

Idle No More: Decolonizing Water, Food and Natural Resources With TEK

Watersheds and Indigenous Peoples know no borders. Canada’s watershed management affects America’s watersheds, and vice versa. As Canada Prime Minister Stephen Harper launches significant First Nations termination contrivance he negotiates legitimizing Canada’s settler colonialism under the guise…

Indian Country must put more effort in public relations

While sipping my morning coffee I began reading a White House document titled “2014 Native Youth Report.” As with every other tribal member, I am aware of the long-standing socio-economic quagmire we have been enduring. The fact that we are still alive and well is short of miraculous and thought…

People Belong to the Land; Land Doesn't Belong to the People

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) does not recognize the right of indigenous nations to own land outside the laws and rules of national governments. According to international historical doctrines of discovery, Indigenous Peoples, non-Christian nations,…

Strengthening the role of Native CDFIs: A conversation with Gerald Sherman of the Native CDFI Network

Roughly 8 percent of the 917 community development financial institutions (CDFIs) in the U.S. are categorized as Native CDFIs (NCDFIs), which means they serve primarily American Indian, Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian communities. Due to a mixture of historical, political, and geographical…

Disenrollment Is a Tool of the Colonizers

Our elders and spiritual leaders do not teach the practice of disenrollment. In fact, disenrollment is a wholly non-Indian construct. Indeed, when I recently asked Eric Bernando, a Grand Ronde descendant of his tribe’s Treaty Chief and fluent Chinook Wawa speaker, if there was a Chinook Wawa word…

One Native's Enterprising Plan to Keep Tribal Resources Within the Community

There are nearly a quarter-million Native-owned businesses in the U.S. today, said Brian Cladoosby, president of the National Congress of American Indians, in his 2014 State of Indian Nations address. And if Thomas Carlson has his way, all those businesses would be listed on a new website he…

What Is Indigenous Self-Determination and When Does it Apply?

Self-determination is an expression often used in discussion of indigenous goals. However, the meaning of self-determination varies among Indigenous Peoples, scholars, international documents, and nation states. The most common meaning of self-determination suggests that peoples with common…

Tribes Get $6 Million in Federal Funds for Energy Efficiency Project

Eleven tribal communities are receiving a total of $6 million toward renewable energy projects and technologies, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced. It is part of President Barack Obama’s ongoing initiative to help tribal nations and Alaska Native villages reduce fossil fuel use, save…

Tribes reach key milestone with jurisdiction provisions of VAWA

The tribal jurisdiction provisions of the the Violence Against Women Act became effective nationwide on Saturday, clearing the path for non-Indians to be held accountable for abusing their Indian partners. Congress enacted S.47 to recognize tribal authority to arrest, prosecute and punish non-…

Political Autonomy and Sustainable Economy

A unique attribute of Indian political ways was noted early on by colonial observers. Indians, Indigenous Peoples more generally, were engaged in everyday political action as full participating community members. Every person had the right to be heard. Decisions were made through discussion and…

Rebuilding Native Nations Course: What I Learned

I had the opportunity to take the Rebuilding Native Nations Strategies for Governance and Development course offered by the Native Nations Institute at the University of Arizona. I was lucky enough to take the online course at no charge through an article I saw on ICTMN. The course costs $75 as of…

Good Data Leads to Good Sovereignty

The lack of good data about U.S. American Indian and Alaska Native populations hinders tribes’ development activities, but it also highlights a space for sovereign action. In coming years, tribes will no doubt continue to advocate for better national data and at the same time increasingly implement…

Dismembering Natives: The Violence Done by Citizenship Fights

Outside Indian Country most don't realize that over the past 10 years, several thousand people have had their tribal citizenship status terminated. Most were not dismembered for wrongdoing or adopted by other Native nations. They were simply identified by their elected officials as allegedly no…

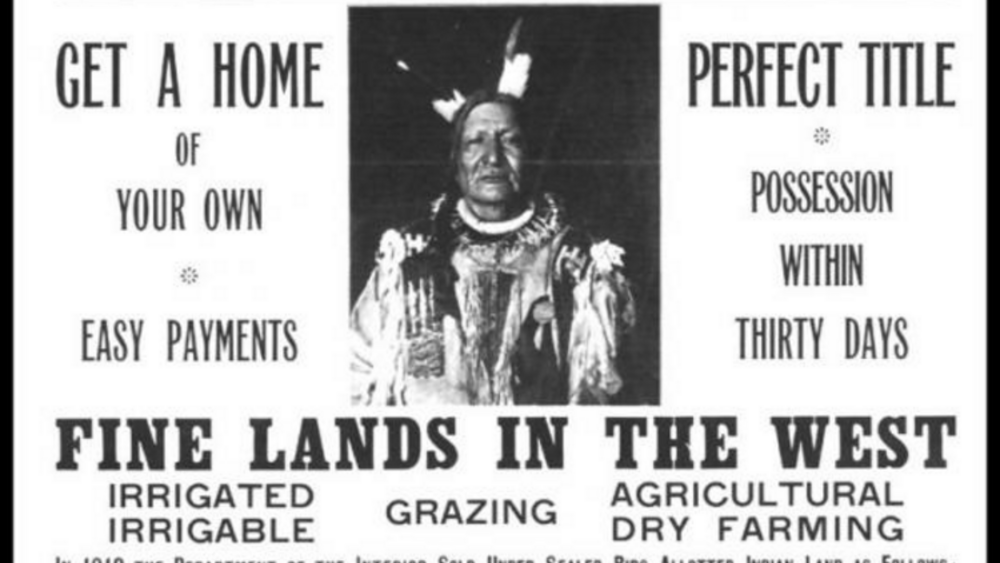

U.S. Land Rights for Indians?

There is an argument within federal-Indian law literature that suggests Indians could have more effectively protected land under U.S. law if they owned land in fee simple rather than under trust. There is better protection for private property under the U.S. Constitution than can be had from…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 7

- 8

- 9

- …

- Last page