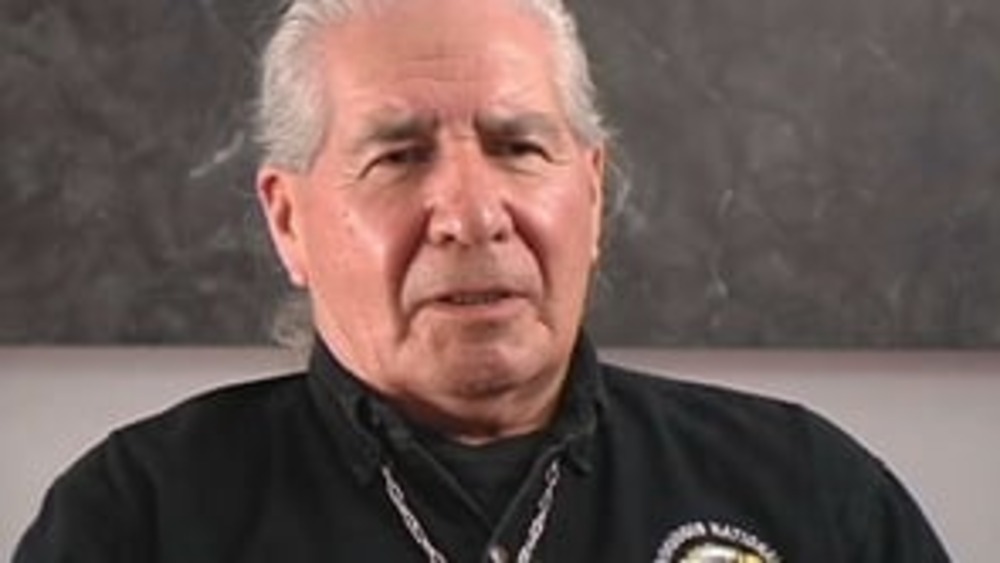

Onondaga Chief and Faithkeeper Oren Lyons discusses the increasingly urgent issues of global warming and climate change and points to Indigenous peoples, their core values, and their reciprocal relationships to the natural world as sources of instruction for human beings to heed in order to combat those issues.

Additional Information

Lyons, Oren. "Looking Toward the Seventh Generation." American Indian Studies Program, University of Arizona. Tucson, Arizona. April 17, 2008. Presentation.

Transcript

“A lot of thank you’s today and I especially want to thank my elders here who gave a blessing and reminded me as well as everybody else that we are connected to the earth very closely and we should be thankful for everything that we do. And that was our instructions: give thanks, be grateful. I want to thank the American Studies in, Indian Studies in Arizona for bringing me here, and Moran for taking the time, and Carol for trucking me about, and to David for taking care of me. And everybody’s been so great to me so I really appreciate it here. Obviously going to have to come back and spend more time. Right now, I’m just on the move, but the reason why is important. It’s my mission to bring news to you, maybe not good news, but news that you should know about and things that are going on in the world.

I come from Onondaga, upstate New York. I come from the Six Nations. English call us 'Six Nations,' French call us 'Iroquois,' and we ourselves are the 'Haudenosaunee.' Six Nations: the Mohawks, the Oneidas, the Onondagas, the Cayugas, the Senecas and the Tuscarora. We’re an old alliance, we’re a confederation based on peace and we were gathered together some thousand years ago to cease fighting amongst ourselves and to become productive in creating and working with one another bringing peace. There was a spiritual being, messenger we called The Peacemaker. He has a name and the only time we ever use that name is when we raise leaders and we raise the [Native language], what you call 'chiefs,' then you’ll hear his name, but otherwise than that we call him The Peacemaker. And he came to five warring nations at that time and I won’t go through the epic story of his life and how he arrived at the Mohawks and how he went from one Nation to the other changing these fighting men to peace. So finally gathered on the shores of Onondaga Lake, where 50 men who formerly were enemies of one another and he laid down for us the whole constitution based on peace, the principle of peace and health, of equity, justice for the people and of unity, the power of the good minds and the power of the collective working together --one mind, one body, one heart, one spirit. And we’ve prospered under that instruction over these many years.

And today I represent in the council at Onondaga the Turtle Clan. I myself am a Wolf. I’ve been borrowed from the Wolfs to the Turtle -- temporarily, they said -- that was 41 years ago. You know how Indians are. So I’ve been there for a long time and the Onondaga Nation is the central fire of the Confederacy and we still maintain our structure of raising leaders and removing leaders. We’re probably the last of the traditional governments still in charge of land. And on our nation at Onondaga, we have no Bureau of Indian Affairs; we’re independent. I just traveled from Sweden to here. I traveled on a passport issued at Onondaga and we’ve been using that passport for now since 1977. It’s an instruction in maintaining your identity, who you are, the importance of being who you are and knowing who you are, instructing your children as to who you are. And most of that comes from songs like Mr. Lopez was singing -- that’s our instruction -- to the moon. We call that our grandmother. We have close relations with the earth. The earth’s our mother. You can’t get any closer than that. And from that point on, we’ve always been instructed by the Peacemaker on many things. When he gathered the people at Onondaga on the Onondaga Lake so many years ago and he instructed us how we would sit and what our clans would be and the authorities and the duties of the women and the men and the people and how this would continue and we’ve maintained that. Now in today’s times, we’re kind of alone in this traditional government, but traditions are everywhere. Every nation has kept their traditions, even though the BIA may be there and even though there may be government authorities, the traditions are still there, songs are still there, language is still there. And the information that’s in the language is what people are seeking today, some instruction.

And so I’ve been a runner for the Onondaga Nation and then the confederacy itself and at times for Indigenous people around the world. I was one of those people who were educated and they said, ‘Well, you can talk like they do. You get out there and you tell them.’ And so I get my instructions from the councils. I don’t have any great wealth of wisdom or so forth. I just understand what I’ve been instructed with and pass that on. Our leaders, our people, don’t like to get up in front of people and speak like that unless it’s our own people. Then they can really speak. So what is the nature of my discussion today, tonight? I had the good fortune to speak to your students here and some of your faculty this morning and it kind of outlined for me what I thought I should be talking about. First of all the introduction of ourselves: the Six Nations has about 18 communities, territories, both about half in Canada and half in the United States. We’re in three states. We’re in Wisconsin, New York and Oklahoma and two provinces in Canada, Quebec and Ontario. And then we have our people all over. Met an Onondaga girl tonight at dinner. She’s over here and her family was here and it was really nice to meet one of my young people here. So we travel far and wide and the message is always the same, it’s always about peace. But today some of the things that were told to us might be helpful here.

When The Peacemaker finally had laid out the whole system for us, he said, ‘Now I’m going to plant this great tree of peace, this great white pine.’ He said, ‘It’ll be the symbol for your Nation.’ He said, ‘It will have four white roots of truth for reaching the four cardinal directions of the earth.’ And he says, ‘Those people who have no place to go can follow the root back to its source and come under the protection of the great tree of peace.’ He said, among a lot of instructions to us as leaders, ‘Prepare yourself for the work that’s in front of you.’ He gave us a lot of instructions. Some of them I’ll tell you about. He said, ‘You as leaders will now have to have skin seven spans thick, seven spans like the bark of a tree,’ he said, ‘to withstand the abuse you’re going to take as leaders. And it won’t be from your enemies, it’s going to be from your family and your friends.’ He said, ‘And don’t wait for any thanks because that’ll be slow in coming.’ He said, ‘Move on.’ He said, ‘When people are angry and they speak in a loud voice, you have to listen to what they’re saying because they’re saying something.’ He said, ‘Try to hear the message through the anger.’ And he said, ‘You cannot respond in kind. Listen. Hear what they’re saying.’ And he said, ‘When you sit and you council for the welfare of the people, think not of yourself nor of your family nor even your generation.’ He said, ‘Make your decisions on behalf of the seventh generation coming. Those faces looking up from the earth,’ he said, ‘layer upon layer waiting their time.’ He said, ‘Defend them, protect them, they’re helpless, they’re in your hands. That’s your duty, your responsibility. You do that, you yourself will have peace.’

So he told us to look ahead. It was an instruction of responsibility of what we are supposed to do. So because I stand here as a representative of our Nation, still carrying the titles, seven generations ago someone was looking out for me or else I wouldn’t be here. So each one of us are any seventh generation and ahead of us are our responsibilities. And we have to take that seriously if they are to have a good life like ours. Our people have gone through a lot of pain and a lot of misery. We’ve suffered removals, genocide, yet we’re still here today. I heard the song and I knew we were still here and everywhere you go you’ll hear those songs. So today as a human being, as a species, I don’t think we have time for being Red or being Black or being White or being Yellow or Brown. I don’t think we have time for that anymore. We have to work together. We have to put aside all of that racism that’s been so destructive, continues. We just don’t have time for that. There’s changes coming and they’re close at hand and very soon we’re going to have to gather ourselves together around the world, and mobilize in our own defense, for our own survival, as a human species. We won’t have time for wars. We’ll need all the money that’s being spent on arms for defense of ourselves and protection of all of nature.

One time, long ago, sitting in the long house when we were having one of our ceremonies, Thanksgiving, we had a visitor who came from the north. He was a Mohawk and they asked him to sing and he was singing the [Native language], the Great Feather Dance. I couldn’t understand Mohawk, but I understood some of the words and then he spoke about my family, [Native word], the Wolf, and I said, ‘What is he saying?’ Because as they sang this Great Feather Dance, there’s a preamble where the beat is slow and they sang and they talk about a lot of things before the dance starts. This was all slow. In our Longhouse, the men are on one side of the house and the women on the other side of the house. So I went down to my grandmother who was sitting there and I said, ‘Gram, what is that man saying?’ And she says, ‘Oh,’ she says, ‘it’s an old song.’ She said, ‘I haven’t heard that in a long time.’ I said, ‘He’s talking about the wolf.’ She said, ‘Yes, he is.’ I said, ‘What is it?’ ‘Well,’ she said, ‘he’s talking about the road to the Creator and how beautiful it is and how we should all be walking in that direction and see the strawberries on the side of the road, the path that we’re taking. The ‘Good Red Road’ they call it, the ‘Good Road.’ And she said, ‘What he’s saying is that on the side in a path like ours, walking beside us is a wolf, both going in the same direction.’ And I said, ‘What does that mean?’ She said, ‘Don’t know. It’s always been a mystery.’

I ponder that a lot of times and I think that he is the representative for the animal world, the spiritual way. And he’s my family, so I’m wondering what does that mean? And I think that he’s like a, well, our uncle maybe. And that whatever happens to the Wolf is going to happen to us. I think that’s what he is. He represents the earth itself and all the life on it. So when you look about and you see what’s going on today and how they’re treating the Wolf, it makes you think that we have to do better, we have to understand. Our nations, they do know about relationship and that’s what it is, it’s a relationship. Our Lakota friends and relatives they say, at the end of their prayer, ‘All our relations, all of our relations,’ and what they mean is literally all life. And when The Peacemaker was instructing the leaders so long ago, he said, ‘Now into your hands I am placing the responsibility for all life in this world.’ And he meant all the trees and all the fish and all the animals and all the medicine and all the water and everything there is, all life, and that’s a responsibility that has kept us here all these years. That’s how we’ve survived. He said, ‘Give thanks, be thankful for what you have.’ And so I see that our nations, the Indian nations, have created great ceremonies of thanksgiving, some that last for days, of thanksgiving and connection with your relatives. And I think that’s what people have to do now in the world. They have to recognize that they are not independent, that they’re just a part of life and you can’t remove all the animals or cut all the trees or catch all the fish without consequence. And so here we are, today’s times facing the consequence of our lost relationship and our lost responsibility.

When we raise leaders in the Longhouse, the old style, what they call the great condolence, it’s a long day. We go through all the laws, all the instructions, instructions to the leaders, instructions to the clan mothers, to the faith keepers, to the chiefs, and then instructions to the people. And it’s the longest instruction when it comes to the people. The people receive the most instruction because they have the most work to do. Leaders are there to help guide you, to be responsible, to initiate positions but the people are the ones that do the work, they’re the ones that have to be the nation. In our language, we don’t have a word for 'warrior.' That’s an English word and it comes from Europe and they were fighting over there. I’ve been traveling over there and I looked at their history, centuries and centuries of fighting. There’s great battlements over there, there’s castles, there’s amazing instruments of war. In Oslo, Norway, there’s a battlement and it starts way back somewhere around the 10th century and each year they made it bigger and bigger and soon it was big enough to hold horses and soon it was big enough to hold battalions of men and it just got bigger and bigger. And I looked on the walls and I saw the armaments and the shields, the axes, the battle axes and they were chipped and broken, heavy swords were nicked and the shields were sliced. And I said, ‘These people fight. These people fight hard.’ I said, ‘It must be hard to be that kind of a life where all you do is fight from one generation to the next.’ We call our men '[Native language].' '[Native language]' means ‘those men without titles who carry the bones of their ancestors on their backs.’ That’s what we call our men, not warrior, '[Native language],' responsible beings, strong men, strong. And they were [strong] or else we wouldn’t be here. And the women right there with them, strong women. Strong families, good instruction, close relations, carried us for a long time until we run across technology of war, weapons and guns, powder.

I won’t go through all that, but all that’s in our history, all that’s in the past and here it is today. And interesting that I’m standing here representative of the Haudenosaunee talking to you about peace and how do you get peace and how do you find peace. You find it by being thankful for what you have and you find it for being grateful for what you have and being in defense of what you have and being closely related to the life that sustains us. We’ve become so independent from the earth itself that we think we are independent and that’s brought us to this point here where we are. Now we’re about to see what the real authority is and how inconsequential we are. We have to work together now. We have to put aside all of this and we have to raise leaders about peace. We have to raise leaders who are going to look out for the people, who are going to look out for the earth and for the lands and the waters. The cod fishing up here off the east banks of the United States is broken; cod is broken. Cod that were once five feet long, hundreds of pounds, down to one and two pounds, fishing them right off the bottom. Can’t fish the cod anymore. Herring, we’re losing the herring. We’re polluting the oceans themselves. We’re polluting the earth itself. We’re leaving a legacy for our children which is really destructive. The high incidents of asthma in children in the east is amazing now, all the kids got asthma and that comes from bad air, that comes from pollution.

And so the instructions that our people had a long time ago still reverberate, long-term thinking, decision making, long-term thinking and you come across the discussion today about bottom lines. What is a bottom line? That’s an economic term, it means the bottom line. Is it a profit or is it a loss? It’s an economic term, that’s what bottom line means. Somebody asked me one time, they said, ‘Well, what’s your bottom line? Everybody’s got a bottom line.’ It caught me a little off guard. I said, ‘Gee, I never thought about that. What is our bottom line?’ And I thought about it awhile. I said, ‘You know, we don’t have a bottom line.’ He says, ‘Everybody’s got a bottom line.’ I said, ‘No, no, no.’ I said, ‘We don’t have a bottom line.’ I said, ‘We live in a cycle, a circle.’ I said, ‘We just go around and around. There’s no bottom line.’ He didn’t have an answer to that, but that in fact is the way it is. Our ceremonies go around the lunar clock, we reach the end it starts over again.

I was talking to the Mayans, our brothers down there in Central America, and I was saying to them, ‘Well, you guys have a calendar that’s coming to an end in 2012.’ ‘Yes,’ they said, ‘that’s true.’ I said, ‘Well, what’s going to happen? What’s going to happen when the calendar comes to an end?’ ‘Well,’ they said, ‘these are 5,000-year calendars so we’ll just start another one.’ Yeah, they made me feel that way too, a little relief there. They did say, though, they said, ‘However,’ they said, ‘there will be a period of enlightenment.’ ‘Oh, what is that, enlightenment?’ ‘Well, you see something.’ I’m thinking, ‘A period of enlightenment, what could that be?’

Well, I thought of this man that was working very hard, decided he was going to take a day off and he was out there on Long Island. Good fishing out there off the Montauk Point in Long Island, big fish out there, come right around the corner. So he said, ‘Well, I’m going to go fishing today, the heck with everything.’ So he went, nice boat, way out there. Hot day. He said, ‘The water looks good. I think I’ll jump in the water, take a little swim.’ So he did. He’s swimming around there, a little ways away from the boat and then he sees this big fin coming towards him, big fin. ‘Oh, no,’ he said. He’s looking at the boat, looking at the fin figuring, ‘how much time have I got?’ Well, that’s a moment of enlightenment. So I hope it’s not going to be that way for us.

The other thing The Peacemaker said was, he said, ‘Never take hope from the people.’ It’s a good instruction. Never take hope from the people. He said, ‘Find a way, find a way.’ So this is hard today, find a way. I’ve been on this road now about global warming for some time and human rights. I’ve been working for our human rights and maybe that’s another section of discussion we should have. In September 2007, September 12th of 2007, Indigenous peoples of the world weren’t peoples. We were populations. In the vernacular of human rights and political discussions in the United Nations, we were always referred to as populations because populations don’t have human rights. Peoples have human rights and for 30 years we’ve been battling in this United Nations for that to be recognized that we are people. And I wondered and I wondered, ‘Why is it or how could it be that there is a declaration, the universal declaration on human rights, so should we not be included and why aren’t we people and why aren’t we included?' Because all those 30 years we’ve been at the U.N., we’ve been developing our own declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. They would not accept the term 'peoples.' They never used that term, we did. They didn’t. And 'peoples' with an 's'. 'People' is a generic term, it means everybody. But when you say 'peoples' with an 's', ah, now you’re talking about Tohono O’odham, you’re talking about Arapahoes, Cheyennes, Apaches, Senecas. You know there’s 561 Indian nations in this country today. That’s a lot of peoples and there were many, many more than that that are gone forever. Still there’s quite a few of us. Here we are. So 'peoples' with an 's', we were fighting to be recognized. Well, on September 13th, the next day, the United Nations adopted the Declaration for the Rights of Indigenous Peoples with an 's'. We made a huge step on the political scene of this world. Of course we always knew we were peoples but that’s a political term and highly charged. We learned that. When you start fussing around there with language, we learned about terminology, what tribes mean, what bands of Indians mean. That’s why we say we are nations. We are nations! The buffalos are nations. They are nations. The wolves are nations. That’s who we are. Yes! But they didn’t think so and we were subjugated.

And how is that, how can that be, how can you take a whole Indigenous people of the world and subjugate them to something less than human? Well, that was done in 1493 by the papal bulls of the Roman Catholic Church and they said in this directive, this bull, they said, this was the pope, ‘If there are no Christian nations in this new lands that you’ve discovered, then I declare those lands to be terra nullius, empty, empty lands,’ old Roman law, terra nullius, ‘Furthermore, if there are people there and they are not Christians, they do not have right of title to land. They have only the right of occupancy.’ And there, one year after the discovery of a whole hemisphere by fiat, it was taken by a declaration from a pope in Portugal. How about that? And we’ve been struggling ever since. We’ve been struggling to come out from underneath that. King of England said, ‘Well, I’m as good as a pope. I like that idea. Works for me.’ So he issued the same directive, 1496 to the Cabots, colonizing the new land. ‘By my authority the land is yours.’ Over here of course, here we were, happily planting. We were planting corn and they were planting flags. Big difference. It was pointed out today, this morning in our session, someone had noticed that just a few months ago that the Russians had taken a submarine up to the North Pole and planted a flag at the North Pole. Anybody remember that? Now why do you think they did that? It’s the Doctrine of Discovery. They took a lot of trouble to get a submarine and go to the bottom, find the North Pole and put the Russian flag there. They were claiming land. And if you remember, when the United States landed on the moon, what was the first thing they did? I think I saw a flag standing there wasn’t it? First thing. Doctrine of Discovery: it’s operational today. So you say, ‘How can that be?’

Well, it became installed in U.S. federal law in 1823 in Johnson vs. McIntosh and the issue was Indian land and Judge [John] Marshall, a very famous judge said, and it was not Indians fighting over lands, it was two white men fighting over Indian land, saying, ‘Boys, boys, boys. You’ve got it wrong,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry, that land doesn’t belong to the Indians,’ and recited the Doctrine of Discovery. And he went back and he quoted the King of England and the Cabots and installed that into U.S. federal law. 1955; Tee-hit-ton Indians made a land claim and they were defeated by the Doctrine of Discovery [in the] Supreme Court of the United States. Gitxsan Indians made a land claim, British Columbia 1991, not very long ago, and they lost the case to the Canadian government based on the Doctrine of Discovery. Last year, small town Sherrill, New York, suing the United Nation of New York for taxes, went to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court said, ‘Yes, Oneidas, you owe them money based on the Doctrine of Discovery.’ So you think that’s an old law? It’s operational today. That’s why we’re having all this hard time. So it’s racist and it’s also religious law, what you call, a country that proclaims that religion and state are separate. Not under those rules they’re not. How can that be?

Well, we’re studying that. We challenged the 'Holy C' because that’s the root of it all naturally and supported by all Christian nations because that became what they call the Law of Nations. They just made up a law and said, ‘Let’s all get in on it,’ so we lost our land. And if you go to court, you’re going to wind up right there. So there can’t be any justice in the court for us. So the paradigms have to change. When people realize that things are so bad and you understand what’s right and what’s wrong, then you have to change the paradigm itself. Common usage, well, if it’s wrong, it’s wrong. So we’re challenging now the Holy C and we did have a meeting. I gave a strong position on treaties and the Doctrine of Discovery last year at the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at the United Nations and 10 minutes after the Holy C came up to us and said, ‘We have to have a meeting,’ because they have a seat at the United Nations. I don’t know why, but the Roman Catholic Church has a seat there. And they said, ‘We’ve got to have a meeting.’ So we said, ‘Fine. Fine. 500 years, about time isn’t it?’ So we went upstairs and we met with their leaders, the bishop, very well versed and he had his lawyers with him and he said, ‘What is it that you want?’ I said, ‘Well, you’re going to have to do something about this Doctrine of Discovery because it’s causing us great pain in the courts today, right now.’ He said, ‘Well, we don’t, we’ve disavowed that many times.’ I said, ‘Well, it’s not good enough. It’s not good enough. You’re going to have to do something better, more profound.’ And he said, ‘What would that be?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘it would be good if your pope confessed to the Indians and Indigenous people that he was wrong, that the Church was wrong; a confession from the pope.’ I said, ‘You people believe in that confession pretty much, don’t you? Good for the soul they say. How about that?’ ‘Well, there’s got to be a better way,’ they said.

So we are in discussion with them. They did write a letter back but in the meantime we’ve talked to Pace University and they have agreed to do a moot court on the Doctrine of Discovery so we’re going to vet this issue. Right now they’re preparing a position to be made at the United Nations in Barcelona, Spain, this fall on the issue of the Doctrine of Discovery. And I would like to see a hearing held in every one of those Christian nations; France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, England, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Sweden. There’s your Christian nations and every one of them should be taught their own history because they don’t know about it, American people don’t know about it but the governments do, they know. So the battle is on. Be that as it may, and we will strive on, but I think before we see the result of that we’re going to be engulfed in global warming and it’s going to take our attention off of everything else except what we’re going to face as humanity.

I was working with a group called the Global Forum of Spiritual and Parliamentary Leaders for Human Survival. Through the ‘80s, ‘90s we were meeting on that issue [global warming] and there were very luminous individuals there like Mother Teresa, the Dali Lama and the Archbishop of Canterbury and Al Gore. Al Gore was talking back then. He was saying, ‘Hey, problem here.’ And we met and we met [in] Moscow hosted by President [Mikhail] Gorbachev, who’s a great environmentalist by the way, knows what he’s talking about. In 1991, we said, ‘Well, how long are we going to meet here? We’re going to meet, just meet, meet, meet and we don’t come to a conclusion, let’s get to a conclusion.’ So in Tokyo, we came to a conclusion and it was four words. After all these meetings, all these years, we came down to four words: 'value change for survival.' If you don’t change your values that are running this world right now, you’re not going to survive. You can’t run on the values you’re running on right now. You’re going to have to change it. You’re going to have to look to the Indians for that change. Thanksgiving, sharing. You’re going to have to share. Not accrue; share everything, big time. We’ve got a chance. We’ve got a chance. Just the fact that you’re all here. If you’re going to wait for leaders to lead you, see you on the other side. You have to do it yourself. You’ve got to do the leading. You have to step forward and you’ve got to speak up in defense of your families and your lives in the future. You don’t have time. Things are just going to get worse. Talk to the Inuits or the hunters up in Alaska they’ll tell you, ‘Whoo hoo, it’s bad up here. Dogs won’t go out on the ice. Hunters don’t know whether they’re going to come back.’ They’ve got to go. They’re subsistence hunters. They’ve got to go but whether they come back is always a question now. They say the same thing in Greenland, same thing in Nunavut. It’s really, you can see the change up in the Arctic Circle better than any other place because it’s really moving at a very fast pace and it’s accelerating.

Now, this is the other thing that you have to keep in mind. The process that we’re engulfed in is a 'compound' action and if you ask what a compound is, compound is what Professor Einstein said was the most powerful law of the universe, a compound. We have two compounds going on right now. One is the ice melt and the other is human population. When I was 20 years old in 1950, there were 2.5 billion people in the world. Here we are 58 years later and there’s 6.7 billion people in the world. That’s a compound, unsustainable and growing as we stand. Every four days there’s another million people born. Did you know that, every four days? That means food, water, shelter and land for every one of those individuals. We’re pressing the caring capacity right now. That’s a reality. It’s hard news, but you’ve got to hear it. And so what do we do? Ah, that’s the question. So you do, you know what you do, you gather your people in a circle, your families, your community and you say to each other, ‘All right, let’s have a meeting here. Let’s have a meeting and let’s decide what we’re going to do.’ And you will, you will decide and you will find a way when you sit and talk to each other like that because that’s how we always used to do. The people will decide. So the fate of our own lives and of the future is in our hands, no one else’s and it doesn’t do me or anybody else any good to say, ‘Well, I told you so.’ That doesn’t mean anything. But mobilization, yes, and this country, the United States has the greatest possibility for change than any other country in the world. We use one quarter of the world’s resources. We’re less than six percent of the population of the world and we use one quarter of the world’s resources. Well, just our change will help a great deal. But that’s the values. You have to make up your mind.

In our meetings overseas talking about energy, a big issue water and energy, because water’s life, water’s food, energy. Well, for so long we were just level -- if you notice, you see the graphs -- for millions of years here we are, human beings just going along like this. And then suddenly about the beginning of the Industrial Revolution they called it, the graphs changed and they start going this way. They start climbing about 1850; both the population and, they’re just together. So what does that mean? It means at one time we were living by the energy of the sun for one day and we could only use one day’s energy. We couldn’t save it, couldn’t store it, there was no electricity, you had to work with the sun and we did. That’s how we planted, that’s how we harvested. We worked with the sun, one day at a time so we couldn’t exceed, there was no way. Well, when we discovered electricity, ooh, things changed. Now there was refrigeration, now there was storage, now there was energy storage and the more energy we made the more we used and if we make more energy today we’ll use more. Why? Because that’s our values; so we have to change our values then. Can we do it? Well, I say yes but that’s really your answer, not mine.

I mean we live at Onondaga, eh, we’re like you guys. We’re pretty close, the same kind of lifestyle but we do keep our ceremonies and we do know who we are and we do give thanks and I think that’s what you’re going to have to do. You’re going to have to find your ceremonies again, you’re going to have to find a way to give thanks, to get your relationship back, to understand how close you’re related to the trees that you’re cutting down, your grandfathers. There’s renewable if you know how to do things, if you’re judicious. Old Indians used to have a game; it was a game everybody played. And you’d be traveling back in the old days and make a camp beside a stream somewhere, river, good place to spend the night, you’d make a camp. Then the next day you would leave but before you left you would put back every leaf, every twig so that the next person coming along would have to look and look and look to see whether somebody was there. It was a game. It was a game about being thankful. It was a way to understand how to keep things so they wouldn’t even know you were there. What a good game. What a peaceful way to deal with Mother Earth. That was our style.

So we have to think about things like that. We have to work with one another, we have to be much more friendly than we always were and we have to share. That’s the biggest issue, share. It goes against the grain of private property, goes against the grain of capitalism, but that’s brought us to where we are today. So if you want to hang onto that, there’s consequence. Our options are fewer and fewer every day. Every day we don’t do something we lose a day. We’re approaching the point of no return when no matter what we do will not matter at all ever. We turn our fate over to the great systems of this earth who will regulate, who’ll regulate our population, will regulate the temperature of the earth and we will be involved there as a consequence. So this is what I’m telling you and I’m not an alarmist, but I have been running this road for a while now and I think people have to know the truth and this administration that’s presently in control has been really negligent about giving the truth of the situation of the earth itself because it interferes with business. Well, Telberg, they said, ‘Business as usual is over. You can’t do business as usual, you just can’t.’ And it’s going to be cooperation rather than competition. You’re going to cooperate. If you’re going to survive it’s going to be cooperation rather than competition. It goes against the grain of this great industrial state here but nevertheless it’s a reality: share, divest, share.

You’re going to have to deal with Africa. You’re going to have to look after Africa. What happens to Africa happens to us. You have to feed people where they live, you have to provide for them, otherwise they’re here. They’ll go where the water is; they’ll go where the food is. So great migrations pushed by circumstance is what we’re looking at. Anyway, I think that we have maybe another Katrina, the fires that you’ve been enduring here, they’re not going to go away, they’re just going to get worse. Fires are here, floods, wind, grandfather. We call them grandfathers, soft winds, but they’re powerful; they’re coming. And let’s hope we have foresight and I say let’s hope we have the will, the fortitude to take on the responsibility of value change for survival. We have to inspect ourselves, every one of us, myself included and we’ve just got to do better. We have to enlighten ourselves, we have to learn, we have to understand what is coming, then you can deal with it. We’re always instructed, ‘Don’t put your head down, never put your head down, keep your head up and keep your eyes open and look and see. Always keep your head up.’ That’s where we are right now. There’s something in the wind, we know that, so we have to find out specifically what it is.

So in that regard, I’ll be a little practical here, I’ve been, I use these books myself and, let me see, here’s one, 2008, called the State of the World: Innovations for a Sustainable Economy. Good ideas in there; practical approach to reality. You can find this book. It’s only about $20. It’s the 25th anniversary of the World Watch Institute and they have a huge science section and they’ve been collecting this information and every year they just add more on so they’re right up to date. Good book to educate yourself. It’s available for $20; you can spare that.

Here’s another one. Plan B, what’s that tell you? Plan B, we’re already in Plan B. Lester Brown. Okay, this is this year. Oh, man, this guy’s got it down. You get through this thing you’ll know what they’re talking about. But he doesn’t leave you without hope. He gives a lot of direction, a lot of ways to move and what to do so you’ve got to keep your head up and you’ve got to move and you’ve got to take, we don’t have time, time’s a factor now in everything really.

Okay. Let’s see what else we’ve got here. Oh, here’s one. Pagans in the Promised Land: Doctrine of Discovery. This is the hottest one. It’s just come out. You can get it on Amazon. Pagans in the Promised Land, this is the Doctrine of Discovery and this really discusses laws and all of the information here. Steve Newcomb. A young man came to us, elder circle 1991 carrying stuff under his arm saying, ‘Hey, you guys got to see what I got here.’ And that’s when we found out about the Doctrine of Discovery. Now it’s, we’re in consultation.

Here’s one: Voices of Indigenous People. This is the first statements that we made at the U.N. [in] 1993, the first time we addressed the United Nations. 1972, I was with a group of people who were trying to get to the United Nations and they wouldn’t let us across the street. We couldn’t go across the street. There was a phalanx of police and we had to be on this side of the street looking at the U.N. building, 1972. 1993, I was the first one to address the general assembly on the dais of the U.N. So the progress, hard fought progress to get there. But these are the words of the leaders of Indigenous people around the world, pretty much the same today as when they were done. But what’s good about this book here is it has the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in its pure form. Now the one that’s passed has been modified. We lost traction here and there but we did keep our main principle but we did lose some. But the original is right here in this book. So some day maybe you’ve got the time to see what that is.

Here’s another one. It’s written by Lindsey G. Robertson called Conquest by Law. This is again the Doctrine of Discovery. And here was a guy that was just curious about it. He got some names and he said, ‘Gee, I ought to follow what happened to these people.’ And he found out that the law firm that was fighting this case had all of these papers and that they put it in a big trunk, it was going to go to England. So he found the family in Ohio and he said, ‘Can I find out where you sent those, that trunk of papers on the Doctrine of Discovery, Johnson vs. McIntosh?’ They said, ‘Well, it never went. It’s downstairs in the cellar.’ So that’s what this book is. So stuff like that, stuff we didn’t have before we do now and things have got to change and fairness to everybody. I’m going to leave some of this stuff with the University.

Do you know that in March of this year that the State of Arizona supported the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a state? Did you know that? That’s a great event, first state in the Union to do that. I have it right here. I was here or up there in, so you can be proud. Here’s the event that’s in here. It also has a complete description of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as it is now. So I’m going to leave that here, people can copy [it] and you can look at statements made.

What else here? I know we have somewhere, oh, here we are. Statement: The ice is melting in the north. This was a statement that was given by the Indigenous people at the United Nations in the year 2000, eight years ago we said, ‘The ice is melting.’ Now they didn’t listen to us then but here we are halfway there but we’ve still got time. So I’ll leave this with you as well. So you’ll have something to work with and maybe it’ll be the great State of Arizona that changes everything, who knows and why not? You’ve got to start somewhere. You’ve got a lot of Indigenous people here, you’ve got a lot of Indian nations here still hanging in there.

So I think that’s enough for tonight, don’t you? I mean I don’t know what you were expecting. But we’re all in it together. There’s one river of life, we’re in our canoe, you’re in your boat, we’re on the same river. What happens to one happens to the other. So it’s in our hands; that’s the end of my message, I think. It’s up to us to organize. They’re doing it in Europe, big time so you’re not going to be alone. You’re not going to be alone. They’re looking for allies. We’re looking for allies. So as a runner from the Haudenosaunee, well, I’m walking now, I don’t run much anymore but I bring you this message as a fellow human being and as a man with a mission and I think it’s a good fight. I think it’s a good fight and I like a good fight. Let’s do it, let’s get on, let’s get on with it. Educate yourself. I’m leaving some stuff here and organize, sit in the circle, talk. Don’t just do something; make sure it’s a good move. Talk it over, work together because unity,

When The Peacemaker brought the five nations together he took an arrow and he broke the arrow, then he took five arrows for the five nations and he took the sinew of the deer and he bound those arrows together, he bound them together hard and then he said, ‘Here is your strength, to be united, one mind, one body, one heart, one spirit, your strength.’ We’re brothers and sisters, we can change blood. That’s how close we are.

Take your time, take your reflections and think about it and ponder it and talk and talk and work your way careful into a good move, strong move. Tell all your relations.”