Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-determination, and treaty rights. The leadership themes presented in these unique videos provide a rich resource that can be used by present and future generations of Native nations, students in Native American studies programs, and other interested groups.

In this interview conducted in October 2003, Jayne Fawcett of the Mohegan Tribe tells of her childhood with her mother’s family, who operated the oldest Indian-run museum in the U.S. As Ambassador of the Mohegan Tribe, Fawcett furthers both her family’s legacy of cultural preservation and her tribe’s economic development initiatives.

This video resource is featured on the Indigenous Governance Database with the permission of the Institute for Tribal Government.

Additional Information

Fawcett, Jayne. "Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times" (interview series). Institute for Tribal Government, Portland State University. Uncasville, Connecticut. October 2003. Interview.

Transcript

Kathryn Harrison:

“Hello. My name is Kathryn Harrison. I am presently the Chairperson of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. I have served on my council for 21 years. Tribal leaders have influenced the history of this country since time immemorial. Their stories have been handed down from generation to generation. Their teaching is alive today in our great contemporary tribal leaders whose stories told in this series are an inspiration to all Americans both tribal and non-tribal. In particular it is my hope that Indian youth everywhere will recognize the contributions and sacrifices made by these great tribal leaders.”

[Native music]

Narrator:

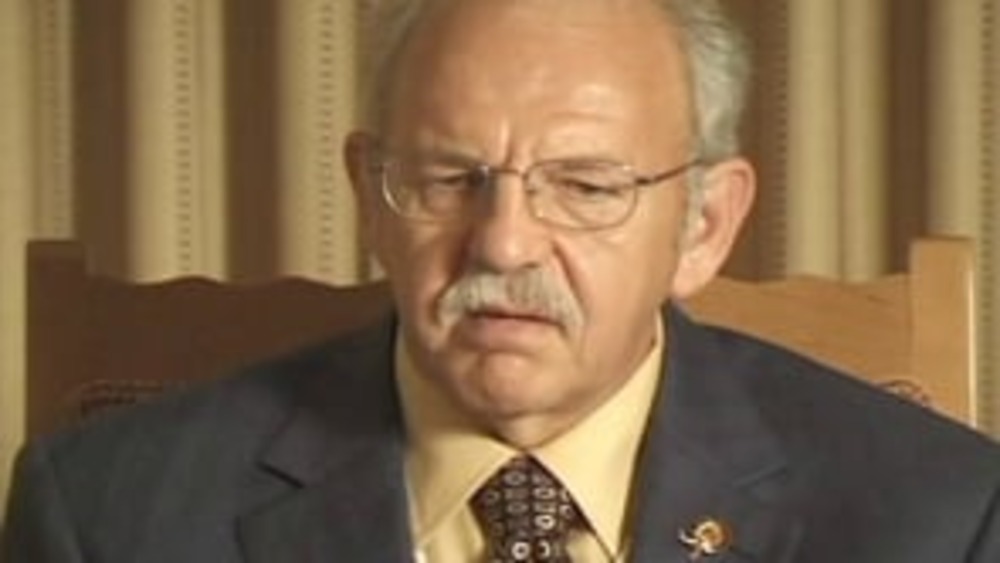

“Jayne Fawcett, currently the Ambassador of the Mohegan Nation of Connecticut, has served the Nation in many capacities, most significantly as Vice Chair and Public Relations representative during critical transitions in the tribe’s history. Today the Mohegans number approximately 1,000 members. Even though upheavals and thefts of their lands in the past were difficult and disillusioning, the majority of the Mohegan Tribe remained in Connecticut and the tribal members maintained a notable cohesion and commitment to their culture, keeping friendly relations with their neighbors. The Mohegans founded a church on their reservation in 1831. Fawcett grew up on the home site of the Rev. Samson Occom, the first American Indian minister in the United States. Her childhood was spent largely with her mother’s family on the home site. The family also operated the oldest Indian run museum in the United States founded by Gladys Tantequidgeon in 1931, a century after the church was built. The museum today continues to display Mohegan artifacts and teach the culture. Fawcett’s aunt and cultural teacher was Gladys Tantequidgeon, medicine woman and powerhouse of the tribe who was 104 years old at the time this interview was conducted. As a child, Fawcett would often go on speaking engagements with her aunt. She would also learn the tribe’s legacy from her uncle, the late Chief Tantequidgeon. Jayne Fawcett went to the local schools where Mohegan children were accepted. After receiving a BA from the University of Connecticut, she became a social worker for the Division of Child Welfare in Connecticut but then decided to enter the teaching profession. A teacher for 27 years in Montville and Ledyard Fawcett was Chair of the Montville Indian Parent Committee. Education has been a major focus of her life. She has been an instructor on Mohegan culture at Connecticut schools and universities and has served on curriculum committees for the local multicultural school. She was an adviser for the projected Native American Studies Program at the University of Connecticut. In 2001 President Clinton appointed Fawcett to the Board of Trustees of the Institute of American Indian and Alaska Native Culture and Arts Development. In the 1970s, while a teacher and a mother, Fawcett became very active with the tribe. In 1978 she became a founding member of the new constitutionally elected Mohegan Tribal Council and in 1990 was elected Chair of the Council of Elders, the tribe’s judicial arm. Shortly thereafter she returned to the tribal council and in December, 1995, took on the role of Public Relations Representative. Jayne Fawcett was one of the key figures in the arduous process necessary for the Mohegans to obtain federal recognition which they gained in March, 1994, becoming the second federally recognized tribe in Connecticut and the 545th in the United States. The day the U.S. Department of Interior made the announcement was full of elation. As one writer has put it, ‘The tribal members had spent 100 years struggling to prove that the world has not seen the last of the Mohegans.’ Since recognition Fawcett has continued her dedication to educate the non-Indian public about the tribe. As she, her aunt and uncle maintain, ‘It’s harder to hate someone you know a lot about.’ Federal recognition has allowed the Mohegans to pursue self reliance and tribal economic development. With its diverse enterprises the tribe has created thousands of jobs for Connecticut. The most renowned project is the Mohegan Sun Casino which pleased even Gladys Tantequidgeon, proud to see so much Mohegan culture and art in the structure’s design. Through all her work Fawcett has maintained solid and joyful family commitments to her husband, daughters and grandchildren. Her husband she says is her champion in tough moments and her own art has not gone unneglected. She is an accomplished organist and pianist and only recently stopped playing the organ at the Mohegan church. The Institute for Tribal Government interviewed Jayne Fawcett in October 2003 at the Mohegan tribal offices.”

Growing up in Uncasville

Jayne Fawcett:

“I went to school in the local schools and because it was a mill town and because we were all poor we didn’t realize we were poor and the Mohegan Indians were accepted. We were together as a group but we were accepted and I’ve always said it that I think Uncasville was perhaps the best place in the country to grow up Indian. And I attributed that partly, well maybe entirely, well, to the fact that we were all poor but also that my Aunt Gladys and my Uncle Harold had built with their own hands a small museum and all of the children in the community would come to that museum and learn about the Mohegans. And they built it with the theory that it’s very difficult to hate people that you know a great deal about and every school child had the experience of coming there and learning about us and not learning so much about the ways that we were different but about the ways that we were alike. And even going back our earlier festivals, our wigwam festival which was really very similar to a powwow was a homecoming for Mohegans and their non-Indian neighbors. And so there was an acknowledgement of difference and a feeling that this was a different community but there was also mutual respect and love. And I think it’s an extraordinary story and maybe somebody should study why Uncasville was always so responsive to us. I can remember when we were going through the federal recognition period and a gentleman came from another town and was berating the town council and the citizens there and telling them that they needed to oppose us and we were going to do this, that and the other thing. And the First Elect man asked him to leave and I really knew I was home and it was, I think that was a memorable moment in my life.”

The museum today

Jayne Fawcett:

“It is the oldest Indian run museum in the United States and it contains a collection of Mohegan artifacts that were handed down in our family as well as articles that were collected by my Aunt Gladys when she worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Arts and Crafts. Well, I guess it was in the ‘30s and ‘40s.”

On becoming Christianized Indians

Jayne Fawcett:

“As you probably know, we would have had our own Trail of Tears had it not been for becoming Christian Indians. We were given the choice to become Christianized or to be removed. And so it was kind of a double-edged thing but we did become Christianized and the Rev. Samson Occom was the first Christian Indian minister in the United States. He set out to build an Indian school with Eleazor Wheelock and this school, he went to England to get money for this school and he got a great deal of it from a man called the Earl of Dartmouth. And this little Indian school grew to be Dartmouth College.”

The story of Gladys Tantequidgeon

Jayne Fawcett:

“Gladys Tantequidgeon is my 104 year old aunt. She is the medicine woman of the tribe. She never had formal schooling. As a very young woman she had to help raise the younger brothers and sisters but she was a brilliant woman. And when Dr. Franks of the University of Pennsylvania was studying the Indians in the northeast, he became acquainted with her and brought her to the University of Pennsylvania where she worked and studied with him there and actually co-published with him and went on with studies to receive an honorary doctorate from both Yale University and the University of Connecticut. She was offered one by the University of Pennsylvania but the requirement was that she had to travel there and at that point in her life it was too great a distance. But she then worked for the Bureau, I believe she was the first Indian woman to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs under Mr. Collier and she worked out west with the Sioux and worked to help them restore many of their traditions. And then she worked for the Bureau of Arts and Crafts and so during this period she collected a great many artifacts and these artifacts are in the museum. And then she returned home to run the museum and she would go on speaking engagements and I would go with her. And she was determined that I would go to college and my mother was too. My father was really, girls didn’t go to college and it was a complete waste of money but she really helped in convincing him that it was important that I go to college. Everything, whether it was bringing me stories of operas or when I was a little girl to just constantly bring me with her and talking to me about our history and about our past, she was I believe the strongest influence in my life.”

School choices and the experience of prejudice

Jayne Fawcett:

“I went to a girl’s school, a very good girl’s school and I was accepted by the girls. This was kind of an interesting thing I think. And it was fine pretty much for me to go to parties where there were girls but then as they got older they were co-ed parties and I wasn’t invited to those. They would have a separate party so there was a difference. It was okay for me to be a friend but it was not okay for me to be a potential girlfriend to one of their brothers. I wanted to live away from home and so the only other sure fire thing was the University of Connecticut so I did go very happily to the University of Connecticut. But I think every time I left Uncasville there was always a stronger feeling of difference and always a stronger feeling of prejudice. So that’s why I’ve lived my life here, Uncasville is a comfortable place for me. Even with my husband when people who are associates of his would make remarks about Indians I would be, usually hostile remarks about sovereignty and things like that I would, with the draw, but now I’ve reached the point in my life where it doesn’t bother me at all. I can deal with that and I realize I don’t even have to deal with that so I guess that’s a growth step for Jayne in this process.”

As a teacher, Fawcett worked with the Indian Parent Committee in Montville: it’s work and concerns

Jayne Fawcett:

“I was a member of the Indian Parent Committee then and there were some very interesting issues that came before us. One of them was bussing. And most of our children went to the Mohegan school and were very happy there because there were other Mohegans there. And so they decided, ‘Well, here are all these Mohegans in this one school, well, that shouldn’t be so we should bus them.’ And what people didn’t understand is that where bussing is good for one minority it may not be good for another minority. Indian children frequently in situations where there are so few of them and when they go to another school there may not be any like them, that for them to have a level of comfort it was important for them to stay together in this one school. And so we had quite an issue. We tried to get the law changed but finally it was agreed that we couldn’t get it changed but that it would be overlooked in this situation. I think it’s very important to impress on people that just because something is good for one minority it is not necessarily good for all of the different minority groups that we have in this country. We thought that it was important to introduce again older children. They’d all been to the museum but we wanted to expand their horizons. We would take them to the ‘Heim Museum in New York and to various Indian sites. We would have them meet with the Indian elders and this was for Indian children and non-Indian children because we felt that it was important for them to learn these things together.”

The impetus behind the Mohegans seeking federal recognition

Jayne Fawcett:

“We had a unique history in that in order for us to keep our land we had to become non-reservation Indians because we were originally, someone said, ‘You’re one of the most recent reservations.’ I said, ‘No, we’re one of the oldest reservations. We had a reservation under King George of England before this country was even a country.’ And so then we became a reservation under the State of Connecticut and we were a reservation before they began to have the reservation system nationally. We’re a reservation under the State of Connecticut and the State of Connecticut had overseers who controlled virtually all business aspects and all important decisions of the tribe and one of the things that happened was that they began to take land for friends and for themselves, illegally but they began to do it. And so we realized that this was happening and in order for us to keep our land we had to become non-reservation Indians and hold it in fee land. I live on land today that has never been owned by a non-Indian. So this was the only, then we saw that jobs were leaving the area and we were very concerned that the fee land that our children had and that the young people had was going to be eroded, they would be selling it, there would be nothing to keep them here and we would no longer exist as a people. And so that’s when the impetus for federal recognition came about. I was afraid of federal recognition as was my aunt. She had worked among people for whom federal recognition had had many negative consequences and so it was a double edged sort kind of. You go along with it because it’s the only way we’re going to survive or is it going to, is recognition going to destroy our people in a different way. So we did not want them to become dependent on the federal government. That was a very great concern.”

Choosing the Bureau of Indian Affairs process over the congressional route

Jayne Fawcett:

“The one thing that the Bureau of Indian Affairs did was that there was such a thorough investigation that there really could be no disputing our legitimacy and so we felt that it was important not to take the congressional route and have it approved by Congress just by an order of Congress. We felt it was important to go through, and I guess it was about 17 years, but we did feel that it was important to take that route and so we did. I don’t know whether we were right or wrong but that was the reasoning at the time.”

Aspects of the BIA process

Jayne Fawcett:

“They collected the records that literally proved that we were tribal just because they wanted to know what pictures, who were the Indians, the Indians in the pictures, what were the weddings. They asked the florist, they asked the people in the schools who the Indians were. They asked the mortician, everyone who had had social contact with us in the area they said, ‘Are there Indians here, who are the Indians?’ and they went to church and counted the Indians in the Mohegan Congregational Church and the children. Unless you’ve been through federal recognition you don’t know exactly how thorough it is. And so all of these pieces came together to form a picture and the picture was one of a tribal society.”

Gladys Tantequidgeon’s response to the new developments with the tribe

Jayne Fawcett:

“So Gladys was very happy and Ruth was very happy finally. Some of her anxiety went away but she was always a bit skeptical and then when the casino was built we were all very nervous because it was, we decided to bring them over to see the casino and Gladys I believe was in a wheelchair ‘cause they couldn’t travel around. She was walking then but they couldn’t travel around, my Aunt Gladys and my Aunt Ruth. So we waited because we were really concerned about her verdict and finally she said, ‘When you said you were building a casino I thought you had lost your culture and now I see that you have not,’ because if you’ve been to our casino it very heavily reflects Mohegan culture. Every aspect in the Earth Casino is representative of our past and we tried to take that past and translate it into the future in the Casino of the Sky because we did not want people to feel that we were an anachronism. We wanted them to understand that things Indian can be as much a part of the future culture of our society as things non-Indian.”

Allies and friends in the recognition process

Jayne Fawcett:

“Our allies were all the older families. If you’d been in town for a long time and you were part of Uncasville and part of Montville, you were our ally. If you were a newcomer and we had a lot of people who because of the Naval base and the Coast Guard Aca, we had a lot of people who were military and people who had just moved into town, they brought with them I think some of the feelings that they had had about Indians from other places. So our allies were uniformly I would say the old families in town.”

Response of government officials

Jayne Fawcett:

“I think we have had a wonderful relationship with all of them. Once again we feel that it’s always important to meet with people and go over issues and usually when that happens we find that we’re really not that far apart and so people who initially were opposed to our federal recognition have become our friends. So I don’t feel that in the State of Connecticut I can say that we have enemies.”

Fawcett brought to the table a knowledge about how people outside of Montville feel about things

Jayne Fawcett:

“The other piece I think that I brought to all of this was what Melissa and I both bring and that is a cultural piece and the insistence on having a Mohegan design to our casino. Our backers initially and everyone told us that this wouldn’t work, people would be uncomfortable with this but we said we wanted this to be a place that people knew they were somewhere else, that they knew they were in a different country and we had a very small reservation and the only place we could shout it was in that casino. And so we even now publish a booklet called Secrets of Mohegan Sun and it literally tells you everything that is symbolic in the casino that is part of Mohegan culture, things that you may look at and not even realize a part of it are. And I feel that if there was anything that I did to influence anyone, this was the most important thing that I did. But I think there’s another important piece that I’ve left out that I, oh, I wanted to share because I think it made a difference for Indian Country. When the Mashantuckets built their casino they were not able to get funding in the United States because at that time no one wanted to lend money to an Indian tribe because of the issue of sovereignty. In other words, you couldn’t recover your losses. And so this is something that people don’t understand about Indians. We can do anything just as well as anybody else given a level playing field. Now if you can’t borrow money from a bank and you can’t borrow money from any of the great lending institutions, you’re not going into business, not even a small business because you have to be able to access the money of the world. And so we were the first tribe, Roland Harris who was the chairman and I with our financial advisers went on the road show and we were the very first tribe to access Wall Street. And because we were able to do that, because we were able to give them a level of comfort through a variety of legal means and without giving up our sovereignty, it opened the door for other Indian tribes to borrow money. And I think maybe that’s the thing I’m proudest of because it always makes me angry to hear people say, ‘Well, I don’t see why the Indians can’t do this, why they can’t do that,’ and they don’t realize that you can’t put things, that the conditions of ownership on a reservation are such that while there are advantages there are also some very serious disadvantages, particularly with regard to establishing a business and borrowing money.”

How the tribe, the local community and Connecticut benefit from the Mohegan Sun Casino

Jayne Fawcett:

“We have a wonderful facility that is making a difference in all of our lives, putting our children through college. How could you ask for more than that? Giving us a place to work. We’ve built homes for our elderly, our medical needs are taken care of, we’ve worked very hard to be the very best employer that we can. You may have noticed as you came in a wonderful facility for our employees. They have their meals here, they have medical facilities here, they have gym facilities here, stores, you name it. We’ve tried to be an exemplary daycare, an exemplary employer and we’ve tried to help the town and other Indian tribes. Yes, Mohegan Sun makes a huge contribution to the State of Connecticut. We have about 10,000 employees and we’re a tribe of about 1800, well, 2000. So of that over half of our tribe, let’s put it this way, is under the age of 18 and then we have our elders so that doesn’t leave a whole lot in here, in the middle and we have some people who are in the service and away or have jobs elsewhere. So I believe it’s accurate to say that virtually anyone who wants a job who is Mohegan and wants a job at the casino has a job at the casino and we have them at all levels I’m very proud to say. We have from vice president on down and we’re very proud of that.”

Citizenship in an Indian tribe

Jayne Fawcett:

“There are many urban Indians who do not belong to tribes. Tribes have their own regulations and blood is only part of that. The federal government would not have given us federal recognition on the basis of our just having Indian blood or Mohegan Indian blood. You had to prove that you operated as an entity or as a tribe and so if somebody’s uncle so and so had been a tribal member 100 years ago and it had nothing to do with us that’s not being part of the tribe. And so it’s not, people need to understand it’s more a citizenship issue than it is a blood issue. Yes, you have to have the blood but are you a citizen of this tribe, are you a member, have you been a part of this tribe? So there is that also.”

Fawcett’s husband and children

Jayne Fawcett:

“My husband is an educator. He has his doctorate in education and has worked in the local, in school administration locally for years and years and he’s currently retired. He’s closer I think to his Indian family than he is to his own. And he has been a great protector of me. There are always instances where people are rude and make inappropriate remarks about Indians and he is my champion. He has always been a champion. Our children are both very concerned about Indian matters and both very active in Indian matters. Melissa as an author and Bethany has been very involved in tribal matters and until recently was Vice President of Marketing of Mohegan Sun.”

If there is a down side to prosperity

Jayne Fawcett:

“I suppose there is but there’s such a greater down side to poverty that I think I would really be a fool to say there was. Everyone suffers for some reason or other. There isn’t a person alive who doesn’t have or experience heartache or a problem. I can tell you it’s much easier to go through that kind of experience when you’re not worried about every penny."

The casino, Mohegan culture and the church on the hill

Jayne Fawcett:

“We can weave and we can have the church on the hill but we also need a way to be competitive in a modern world and the casino is the one way that we have been able to do this. It’s been very important for us. There have been people who have negative views of casinos. Gambling has been something Indians have done from time immemorial and I honestly don’t understand the problem that people do have with gaming when I think of even the most benign institutions such as the church. More people have died, died in the name of God than have been injured by gaming and any, anything taken to its extreme whether it’s credit card use or too much food, too much drink, too much sex, anything taken to the level of misuse and overuse can be a compulsive habit and be bad for us. So when you go to the movies, if you take the family you probably spend $50 and you come home with entertainment. When you go to the casino, you may spend the same $50, you come home with entertainment if you lose but if you don’t, you may come home with a great deal more. So I don’t understand the prejudice, and I think I have to use the word prejudice, that we have against gaming. I can only suppose that it stems from the gambling for Christ’s robe that the negative connotations to gambling came about. We have negative connotations toward overuse and abuse of alcohol, justifiably so, overuse and abuse of credit cards or anything you can think of but somehow they don’t carry with it this, oh, I don’t know, quasi low life feeling that people have put around gambling and it’s one I don’t understand because if you look at the facilities they’re magnificent, they’re fun. We offer entertainment for old people who can’t get around. This is a place where they can go and have fun. Do some people abuse it, sure. Do some people abuse religion, sure. Credit cards, food, you name it, it’s all in the abuse of the system that the problem lies. And we have been working on restoring that part of our language. We have cultural classes of course so that the traditional skills are not lost. We work very hard, we have prepared an educational program for the State of Connecticut on Indians of the area so that it can be available to schools and it goes through all the levels. It’s really hard for me to remember all of the pieces that all we have put out into the community to help and to help them know us.”

Fawcett is on the Advisory Board of the Museum of the American Indian and has received several national appointments

Jayne Fawcett:

“I received a presidential appointment from President Clinton to the Institute of American Indian Art, a wonderful, wonderful Indian school in Santa Fe. I enjoyed my tenure there and am very grateful to have had that opportunity. And I was also appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury as one of two Indians to be on the Tax Exempt Government Entity Advisory Committee. That was also a unique experience given my relative innocence on tax related matters but it was a challenge, let’s put it that way.”

The United South and Eastern Tribes, USET

Jayne Fawcett:

“I’m on the Board of Directors and the Treasurer of the United South and Eastern Tribes and I’m extremely proud of this group because it is a dynamic example of Indians working together. Our motto, ‘because there is strength in unity,’ has really helped us in meeting with legislators as a group and trying to help them to understand how some issues would negatively impact on Indian Country as well as to understand some of the needs of Indian Country. So this has been important, perhaps one of the most important things. We work together as a group and so do the ambassadors work together as a group. We work together also on health. USET virtually handles, acts as a conduit for a lot of our health issues with Indian Affairs so that, there are very, there’s housing and health and finance, there is a cultural group. I hate to leave any of them out but there are a variety of groups all of which present resolutions to the United South and Eastern Tribes and we then send them to the appropriate authorities with the backing of all of the tribes in the east and that’s a powerful impact. It’s powerful when the leaders or the members of the board of directors go to meet with a congressman or to meet with a senator about an issue. When you represent all of those tribes, you have a voice and we also work financially together.”

Fawcett has served as her tribe’s liaison on environmental issues

Jayne Fawcett:

“I did work heavily during the last council with environmental issues and I think we’ve done some unique things with what we call Knox credits which are things that we do to offset any pollution that we may be creating. But environmental issues have been extremely important to us and we’ve done some very innovative things with them in the casino.”

Electoral politics on the tribal level

Jayne Fawcett:

“We have a great many people who run. When there’s a council election, there are a large number of people who run. We have a tribal council of nine and a council of elders of seven so basically that’s it for the electoral politics. It’s basically the legislative and the judicial branches of the tribe, tribal council being the legislative and the council of elders judicial.”

And partisan politics on the national level

Jayne Fawcett:

“We try very hard to work with both sides of the aisle because we feel that that’s the only way we can have a complete understanding in Congress of what Indian Country’s needs are. We have learned about business and how to be competitive in business and just watch us go, just watch us go.”

The most deeply rewarding work

Jayne Fawcett:

“I have to say family with a caveat because you see the tribe is my family and so we are literally a family, we are all no more than third cousins so family and tribe are really intermingled so that one is really indistinguishable from the other and so it has to be my large family, my global family, the tribe.”

And greatest sadness

Jayne Fawcett:

“I guess my greatest difficulty still is dealing with bigotry. It was a sadness that begins as a child and never leaves. I do see that changing and I’m very happy to see that changing and I think its basis lies in ignorance and as we see a more informed public, as we see a more informed country and a more informed world, we’ll learn what I learned to teach years ago at the museum. It’s not how much we were different but how much we were alike.”

The future of the United States and of Indian tribes

Jayne Fawcett:

“My uncle always said that it was non productive to look back in anger, that if you devoted yourself to feeling sorry for yourself or to be angry about past wrongs that you really crippled yourself from happiness and from doing worthwhile things that make a difference in the future. And I think that’s the direction we’re heading. I think we really are learning. I think we’re growing up. I feel that the greatest threat to sovereignty of tribes are individual interest groups that can influence legislation and slide pieces of legislation in without hearings, without government to government consultation with Indian tribes. I think the biggest plus for Indian tribes is going to be the enforcement of government to government consultation on those issues which involve Indian tribes. This hasn’t happened yet but I think we’re moving down that path because people are becoming more and more aware of them.”

Fawcett loves her role as Ambassador of the Mohegan Nation

Jayne Fawcett:

“Each one of us on the tribal council has an area of not expertise but an area that where we feel comfortable. For example, someone may be very good in development, someone may be in environmentalism. We have someone who does a great deal of social service work. We have another who is very good at business, our treasurer is extremely good at business and has had a business background, as does our vice chair. So each of us takes a piece of council obligation I guess and oversees it.”

The Mohegan Congregational Church and tribal culture

Jayne Fawcett:

“The Mohegan Church is very, very unique. Our minister has participated in a pipe ceremony. We have had Mohegan religious ceremonies at the church. There is an eagle feather that hangs face down above the pulpit which is a symbol of peace and that this is a holy place. We had one minister tear it down and he was dismissed and we put it back up. And so the church has played a dual role. It has been a site where traditional Indian observances are held as well as Christian observances so it’s an unusual place. They aren’t in conflict.”

The legacy she would leave for her tribe

Jayne Fawcett:

“I guess the legacy I would like to leave is that I’m not an individual, I am part of a continuum and we all think of ourselves in Mohegan as part of a continuum, that it’s not what an individual does, it’s what we have all done as we’ve come along that has made the path better. And so I hope that when the Mohegans see this that they will work even harder to be part of that continuum and further our tribe.”

When non-Indian view her story

Jayne Fawcett:

“I hope they will say, ‘I can’t understand what she was talking about when she mentioned prejudice and bigotry.’”

For the celebration of federal recognition, Fawcett wrote a song

Jayne Fawcett:

[Fawcett singing]

The Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times series and accompanying curricula are for the educational programs of tribes, schools and colleges. For usage authorization, to place an order or for further information, call or write Institute for Tribal Government, PA, Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon, 97207-0751. Telephone: 503-725-9000. Email: tribalgov@pdx.edu.

[Native music]

Videotaping and Video Assistance

Chuck Hudson, Jeremy Fivecrows and John Platt of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

Editing

Green Fire Productions

Photo credit:

Jayne Fawcett

Mohegan Nation

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times is also supported by the non-profit Tribal Leadership Forum, and by grants from:

Spirit Mountain Community Fund

Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs

Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, Chickasaw Nation

Coeur d’Alene Tribe

Delaware Nation of Oklahoma

Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe

Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians

Jayne Fawcett, Ambassador

Mohegan Tribal Council

And other tribal governments

Support has also been received from

Portland State University

Qwest Foundation

Pendleton Woolen Mills

The U.S. Dept. of Education

The Administration for Native Americans

Bonneville Power Administration

And the U.S. Dept. of Defense

This program is not to be reproduced without the express written permission of the Institute for Tribal Government

© 2004 The Institute for Tribal Government