Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-determination, and treaty rights. The leadership themes presented in these unique videos provide a rich resource that can be used by present and future generations of Native nations, students in Native American studies programs, and other interested groups.

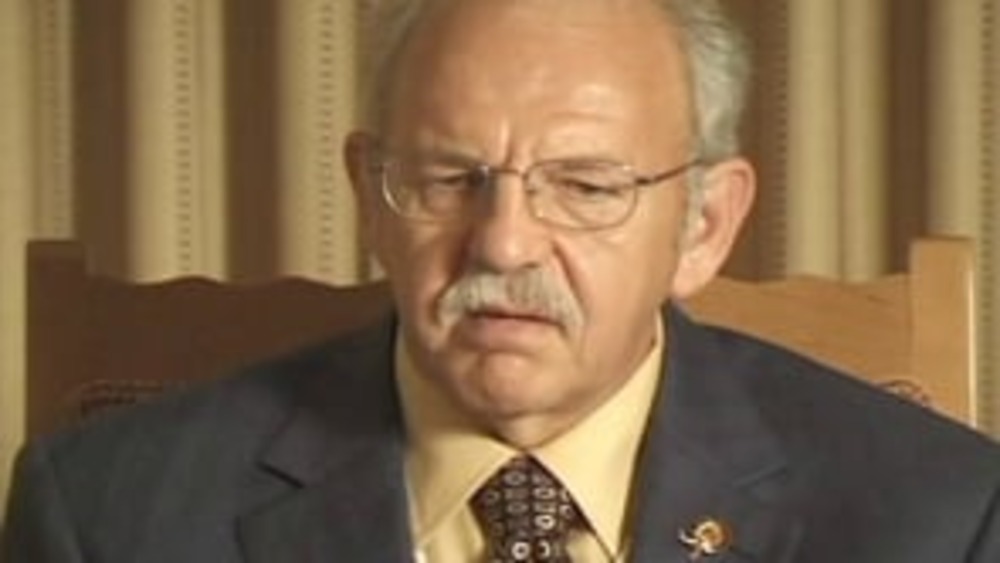

Institute for Tribal Government Director Roy Sampsel is convinced that tribes have unique skills as natural resource managers. Sampsel often serves as a bridge between tribes and federal, state & local agencies. His past positions include Executive Director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, Special Assistant to the Secretary of Interior for the Pacific Northwest Region, and Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Policy, Department of Interior.

This video resource is featured on the Indigenous Governance Database with the permission of the Institute for Tribal Government.

Additional Information

Sampsel, Roy. "Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times" (interview series). Institute for Tribal Government, Portland State University. Portland, Oregon. 2004. Interview.

Transcript

Kathryn Harrison:

"Hello. My name is Kathryn Harrison. I am presently the Chairperson of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. I have served on my council for 21 years. Tribal leaders have influenced the history of this country since time immemorial. Their stories have been handed down from generation to generation. Their teaching is alive today in our great contemporary tribal leaders whose stories told in this series are an inspiration to all Americans both tribal and non-tribal. In particular it is my hope that Indian youth everywhere will recognize the contributions and sacrifices made by these great tribal leaders."

[Native music]

Narrator:

"Roy Sampsel has had a decade's long fascination with fish, water, forests, oceans, wildlife and the rights of Indian tribes. More than a fascination, he has maintained a steady and creative commitment to the sovereignty of Indian Nations and the protection of their natural resources. As a policy advisor to the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission he has worked to protect, enhance and implement the tribal fishing rights of the Warm Springs, Yakima, Umatilla and Nez Perce tribes. Convinced that tribes have unusual skills and abilities as resource managers, he has worked behind the scenes and in front of the scenes to make sure tribes have a very solid seat at the table in the complex natural resource negotiations among federal and state agencies, tribal nations and other interests. Roy, who spent his early years in Broken Bow in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, is both Choctaw and Wyandot. His is a member of the Wyandot Nation. When his father went into the Navy in World War II, the family stayed with Roy's grandmother, a storyteller and a savvy strategist in conducting business with tribes on the reservation. She would often take Roy down to a tribal gathering place, one of the old creeks on the reservation on whose banks Roy says, ‘still stands a huge cottonwood tree.' The Sampsel family moved from Oklahoma to Tulane, Louisiana, then to Portland, Oregon, where Roy got the spark for public service from professors at Portland State University and from Oregon political leaders of both the Democratic and Republican parties. After working at the Oregon Legislature, Roy had the opportunity to go to Washington, D.C. where he served from 1971 to 1976 as Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Interior for the Pacific Northwest Region. He was responsible for assisting the Secretary in developing and implementing departmental policy for federal resources and for a liaison with tribal and state governments and federal agencies throughout the region. From 1977 to 1979 he served as the first Executive Director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. He returned to Washington in 1981 serving as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs for the Department of the Interior. In this position he worked on Indian rights protection and natural resources policy including timber, fish, wildlife, oil, gas and minerals. He also worked with the Bureau of Indian Affairs on putting into action the Indian Self-Determination and Education Act of 1975. He relished participating in a great time of legislative accomplishments on behalf of Indian people. Roy Sampsel is known as a generous, openhearted leader. Helping people figure out how to solve problems is a pleasure for him and he will often say in reference to periods of challenge, difficulty or accomplishment, ‘I can't even tell you what an absolutely wonderful time that was.'"

Roy Sampsel's family lived in Broken Bow and Tahlequah in his early years. When his father went into the Navy for World War II, the family stayed with Roy's grandmother

Roy Sampsel:

"My mother was the youngest of 13 children and I was the youngest of all of the grandchildren so we had a great sort of time with my grandmother. She had a great deal of influence on my life at the time. She was a great teacher and spoke all of the Indian languages for the civilized tribes in Oklahoma: Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, Seminole and Chickasaw. She was an interpreter if you will for a lot of people who were trying to figure out how to do business or have dealings with the individual tribes. She was a fascinating woman. I can still remember her asking me how old I was as I was getting to be tall and taller than she was. And so I can remember when she took my hand, and I didn't think very much of it at the time, but kind of pronouncing that I was a man now, I was no longer her little boy. Of course that was the youngest of all of her grandchildren that she'd had. I had a lot of uncles that were gone before I was ever born of course because they had died in the first World War and I can remember granny saying to me that two of the saddest things that had ever happened was one, losing me as a baby cause I was now a man, and living longer than most of her sons."

Roy's father became a psychiatric social worker and the family eventually moved to Portland, Oregon. Roy had a variety of school experiences from Broken Bow to Portland.

Roy Sampsel:

"When we were in Broken Bow it was an Indian school in Tahlequah. I'm not sure if it was a state school or an Indian school but it was all Indian students. And then in New Orleans we lived in the student housing section at Tulane, which was a relatively wealthy section of New Orleans at the time. So it was not unusual to go to school in New Orleans and have classmates delivered there in their family limousine. So it was relatively...I wish I could remember the, there was a Mexican student. Anyway, he and I fought every morning with all the other kids. So it was kind of fun. Finally got a teacher who said, ‘that's not really a cool thing to do.' Franklin High School was a place where I decided; it's where I kind of developed my political student government interest, that type of thing. I was always better at politics and student government than I was at school itself, which was one of the things that was fun about Franklin. It was a place in which I got a lot of encouragement both from other student leaders that had been there prior to me getting interested and a faculty that was encouraging folks for that type of participation."

Roy learned from his professors at Portland State and from political leaders like Senator Mark Hatfield and Oregon Governor Tom McCall

Roy Sampsel:

"Dr. Garboni had one of the greatest and funniest lines about me ever. There was a student/faculty committee that they were appointing students to participate with faculty on the committee and he was advocating that I be one of those students and he was talking to his other faculty members at the faculty meeting and said, ‘Roy Sampsel is the smartest C student I've ever had.' That was kind of the classic reference to me. I was always the smartest C student that a bunch of these guys had ever had but we had a great time together and we got to be very, very close friends. And the University and the students that were there at the time had that opportunity to have that great sort of dialogue of politics and public service and communication at the same time."

After honing his skills in a job at the Oregon State Legislature, Roy went to work for Secretary of the Interior Roger Morton

Roy Sampsel:

"In the early part of the Nixon administration and he'd been the first kind of easterner that had been named Secretary of the Interior and we had...so they were looking for somebody that had a little bit of public affairs experience but who also understood some of the Western politics to work with him and Roger C.B. Morton. So Rog Morton was the Secretary of Interior starting in '71. He had actually got...I guess he started in '70 but in '71 they said, ‘We'd like you to come and work as part of his communication team,' and that was done primarily because of the political context. We did not know each other. We'd never really met. But some of the western Republicans were a little bit nervous to have this east coast guy running the Secretary of the Interior. And that was a great opportunity for me cause it kind of reintroduced me back into Indian affairs at a political level and at a level in which we had a lot of changes taking place. So here I was this basically Indian kid who had left Oklahoma, came out to Oregon, got involved politically in those types of public affairs types of discussions, had gotten involved politically both in terms of Democrat/Republican politics, now going to work for a Secretary of the Interior who had huge Indian issues on his plate. At the same time you had U.S. v. Washington taking place. So those were very high profile Indian treaty fishing cases. At the same time you had Wounded Knee going on, Alcatraz, the takeover of the BIA building in Washington, D.C. A very good friend by the name of Louie Bruce who was the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C. Louie Bruce was...ended up being a very great friend but was a person who had...they teased him when he first got in by saying that he was the only Republican Wall Street Indian they could find. Louie had worked in public affairs and worked in advertising and kind of the fame and fortune of creating the slogan for Miller Beer, ‘The Champagne of Beer,' was very well written and had been successful both financially and business wise, came in to be the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs at the time as the Commissioner when it was exploding with AIM and Wounded Knee and ended up being perhaps the only person during that period of time that could have held things together. He ended up...he's passed away now but he ended up being a great friend and everybody remembered him as probably the Commissioner of the 20th century for that period of time."

Major fishing rights and environmental issues came to the fore in the early 1970s

Roy Sampsel:

"So the environmental issues were huge. Legislative wise, you're at a period of time in which a small, relatively small group of people are working with a Democratic Congress to figure out how you're really going to implement, NEPA, the National Environmental Protection Act because it had just been passed a little bit earlier and now you had huge issues like what was the NEPA requirement to build something like the Alaska pipeline? Well, part of the excitement of the time was that with all of these issues, all of which touched each other, the environmental issues touched each other, the treaty right issues had tremendous implications to what it would mean in terms of the fishing relationship between Canada, the United States and Alaska because you had those fisheries all of which went into the various jurisdictions, none of which had been resolved yet. You had major pieces of legislation that were being passed. Indian Self-Determination and Education, the Nixon administration came out with a major Indian policy, hadn't had one in literally decades and it said, ‘Indian self-determination without termination reversed the termination policy of the ‘50s; major, major policy statement of fact. But with everybody kind of struggling about how would you implement that, what did it mean in relationship to AIM and the real poverty and problems that are taking place on Indian reservations? What did it mean in relationship to those environmental concerns that are now becoming very, very sensitive and key both to the treaty and legal obligations that the United States had for Indian tribes? So we were passing things like Endangered Species Act, same time frame. Clean Air, Clean Water Act, implementation of NEPA and then how are you going to co-manage between tribes and non-Indians, major resources like the fishery resources that had been in the courts. So it was within that sort of context that not only did I get the opportunity to work with the Secretary of Interior but with the other assistant secretaries that were dealing with these issues, all of which were pushing this sort of environmental Indian awareness climate together with some very significant changes that were taking place both within the Congress and within the administration. So an exciting five or six years."

The excitement of converging issues, Native treaty rights, the environment, economic development

Roy Sampsel:

"I think it was the sense that there was great change taking place and that no individual change, act or personality was insulated from the other. Nat Reed was an assistant secretary for Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Nat had kind of an Ichabod Crane character about him because he was thin and came out of Florida and he had wealth. He essentially was one of those people who had served on a number of commissions and a number of positions in government basically for a dollar a year because he had this great sense of social responsibility. And so in this Nixon administration he came in with this wonderful sort of environmental ethic that had been gained during this period of time. I can still remember Nat trying to understand the relationship between the Native rights in Alaska and his concern for building parks and refuges and how was he going to do that with this Native Indigenous subsistence right. It didn't seem to fit. So here was this wonderful person wrestling with what his job was in relationship to this overriding responsibility that he had...you couldn't learn it in school, you hadn't been taught it, there wasn't a place to easily pick I up, with an administration who said, ‘Hey, Indians have rights and Indians have their right to be self determined and educated.' This sounds a little silly to be doing that in the latter part of the 20th century but in fact this is when it was starting to come together or back together again in this sort of awareness. You also had a political climate in Alaska that said, ‘We don't want reservations. We don't want this settlement of this lands issue and the building of this pipeline which is very, very important to us economically to be hampered by the fact that we're creating reservations in this state.' Therefore you ended up with something called the Native Claims Settlement Act which essentially changed the character of Native people by creating corporations."

The Alaskan Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 was a money-land settlement with Alaska Natives establishing regional corporations and terminating certain rights

Roy Sampsel:

"Thirteen regional corporations, village corporations, that would be given land and resources from the oil revenues as the means by which to insure that there would be success or assimilation of Native people into the broader society without what was perceived to be the inherent failure of the lower 48 reservation Indian situation. So when you asked what was there, you had all of this coming together at a time in which it hadn't been sorted out but you knew that this was, that period of time was in fact going to be a major change and if you can get involved with pieces of it maybe you could help make some of those changes better."

As special assistant to the Secretary of the Interior he had frequent contact with tribal communities

Roy Sampsel:

"In Alaska I probably went to I would say at least half, maybe 60 percent of all the villages and it was a timeframe that was just absolutely fascinating. I had not spent any time in Alaska before doing that so getting a chance to meet the tribal leaders, getting a chance to meet all the people that was very, very exciting. In the lower 48 the answer is, yeah, I got to spend a lot of time talking to tribal folks about a range of issues and the...I think probably some of the most tense times were when we were dealing in Sioux Country around the Wounded Knee timeframe. Up in Red Lake; that was during a period of time in which all of this was taking place. You had Roger Jordain under a tremendous amount of fire from the dissention within the tribe and its own people. So yeah, I spent a lot of time with a lot of folks. The difference in doing it at that particular level is that you were essentially talking to leadership about a issue of the moment as opposed to where do you want to be in a few years, where do you see the change taking you and that was kind of the exciting part about dealing with specific issues cause you could actually sit down with the folks that were involved in the fish commissions or getting involved in the fish commissions in the later ‘70s. And they had a vision of where they wanted to see things go and what they were trying to fight and protect for."

Tribal leaders of the recent past, Roger Jordain, Red Lake, Chippewa Cree; Wendell Chino, Mescalero Apache; Bob Jim, Yakima; Lucy Covington, Colville

Roy Sampsel:

"Respect for each other but they disagreed a lot on a lot of things and they were grand leaders of their time. They were cutting edges in a time in which the things that they had had to fight for were changing a little bit. They were very distrustful of government and what it was trying to do but also very demanding that government had a responsibility, that those treaties meant things, that there was a trust obligation of the United States that extended beyond the Bureau of Indian Affairs and that it wasn't just based upon the land, the treaties talked about education, it talked about healthcare, it talked about those things that were a piece of the federal trust responsibility. Yeah, they were very articulate spokesmen and they had visions for their people. I don't know that anybody will ever really understand what Wendell Chino did but he was a rock and there was no question about it, there was that sort of presence. When he was there to make a comment and to talk about things, you knew it was worth listening to and you knew it was serious. There were a number of people during that same period of time that we're going at. Yakimas had a...Yakima tribe in Washington had Bob Jim. Bob was a wonderful, strong Indian leader. When the Native people in Alaska were wrestling with how they were going to deal with the Native Claims Settlement Act, Bob Jim went to his council and said, ‘We need to help these people.' The Yakima tribe loaned the Alaskan Native leadership $250,000, which was a lot of money in those days, a lot of money today but a lot of money in those days, so that they could get organized to deal with the federal government because he believed it was that important. I was dealing with a water rights issue at the time because I was working in Interior. And we called all of the tribal leadership and tribal attorneys together to deal with this particular question and a lot was going on, it was a two day meeting. We were into the second day and I can still remember Bob Jim standing up and saying, ‘Well, Roy,' he said, ‘I really enjoyed the fact that you've been doing this today.' He said, ‘I'd like to ask all of the non-Indian folks that are here just if they wouldn't mind leaving for awhile so some of us Indians can get together and talk about this a little bit.' He was very courteous about it and at the end of that they...of course people started picking up their things and leaving cause they respected Bob Jim's desire. And about...as they were starting to leave he said, ‘Now, Roy, I want you to stay.' He said, ‘I want you to stay.' So he got in there and he shut the door and he said, ‘I want you to understand what water means to me and what it means to...' and he went around the room because he said, ‘I think you're dealing with this in too much of an abstract legal sense. There are attorneys to deal with it legally but this is what water means to us.' It was dynamic and these were people who understood what it meant to be Indian, understood what it meant to be Indian in a time of conflict and controversy."

The Indian Self Determination and Education Act of 1975 gave tribal governments increased control of their affairs and funding for education assistance

Roy Sampsel:

"What I think the legislation that changed the character, that represented a major shift if you will in federal policy was the Indian Self-Determination and Education Act. Not because of the detail of the act but for the recognition that tribes were in fact not going to go away. That the termination and the assimilation era that had been in the ‘50s and early ‘60s was not where we wanted to be as a nation anymore and that there was a recognition that tribes had the ability to not only run but operate their own form of government. So the significance was this major change. The other piece that was significant about it is that this came about during the timeframe in which you had guys by the name of Forrest Girard who was working on the Indian committee with Senator Scoot Jackson of Washington. Scoot Jackson had been one of the architects of the termination period and here was this man, chairman of this committee, with Forrest Girard an Indian person working on his stand, working with the administration to create this piece of legislation. It was a significant turnaround and Indians seizing upon that as the means by which to identify how they chose to do business with the federal government and how the federal government were going to have to respond to them in the future."

Working in the administration of President Richard Nixon

Roy Sampsel:

"It would be wrong to characterize him as a person who had this great passion for Indian self-government and the rest of it. What he did is he understood that there were people who did and he let them move forward in a way that I think speaks well for his overall leadership. It was a time that it may have happened anyway regardless of who was president. I don't want to give too much credence to some of these things that just are necessary and are evolving anyway. So if you look at the Nixon timeframe, he did things like return Blue Lake to the Pueblos, his tremendous culturally significant event because he knew that Indian self-determination and the right for tribes to have this sort of... required specific actions that would demonstrate there was in fact a change."

Roy returns to the northwest to work with tribes keeping old friends and allies

Roy Sampsel:

"I decided that there were a couple of things that needed to happen. One, I wanted to work closer with the Indian issues on a specific basis and I was fortunate enough to be in the northwest and the fact that you had a few things that had been achieved in the federal courts didn't mean that they were being implemented and the question was, ‘Could you implement a court treaty right? Could you make it work?' And we had the advantage of having some great Indian leadership at the time and some pretty gutsy folks that were sitting around trying to figure out how to make that happen. And tribes had understood that they were gaining in terms of their management responsibility and that they weren't going to go away. A guy by the name of Wyman Babby had been back as a young Indian person working with Louie Bruce. Louie Bruce, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, first chairman of the Nixon administration and he had ended up being the area director for Aberdeen, Wounded Knee, young Indian man basically beat up by that period of time. I brought him on my staff in Portland, Oregon, in the Secretary's office because quite frankly he didn't have any place else to go. He was looking for...he still wanted to be active so I take Wyman Babby and let him go work for Don Hodel. During this period of time Don Hodel says, ‘Gee, there's this treaty thing going on with Indian fishing rights and we're right kind of in the middle of it, aren't we?' And the answer is, ‘Yes.' So this is a period of time in which Wyman Babby, because of his education and the opportunity to work with the Indian people out here, has determined that maybe what Don Hodel ought to do is be the one who leads the charge. So during that period of time on the Columbia River you've got Don Hodel working with the tribes to reach the first agreement between the treaty tribes and Bonneville Power Administration that they have a seat at the table to deal with these issues."

The Columbia River Treaty Tribes, Yakima, Nez Perce, Warm Springs, Umatilla

Roy Sampsel:

"That memorandum of agreement between the four tribes signed by the Bonneville Power Administration really broke things open because it made the state very nervous and very unhappy. So that agreement was then modified and was signed also not only by the four treaty tribes and the Bonneville Power Administration but the Governor of Idaho, the Governor of Washington and the Governor of Oregon. The Governor of Oregon at the time was a guy by the name of Bob Straub, Dan Evans in the State of Washington and Cec Andrus in the State of Idaho. And so during that period of time is when you get the commissioned organized, that's when you get the tribal Indian commissions organized, you get this sort of expansion if you will of that authority, get the negotiation between the Puget Sound tribes on the U.S. v. Washington, the Bolt decision timeframe because the administration wanted very, very much to have a settlement of that court case. So there was a formal negotiation with the tribes, the State of Washington and President Carter had three cabinet officials as part of that team, the Attorney General, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of Interior. While all of this is taking place within this context about how do we begin to implement a court case and what is the United States' responsibility not only to file the case and to win it but then to implement it to make sure that the intent of that court case is in fact carried out, how much resource in terms of money is needed so all of this is being debated. How much authority do tribes have? What does co-management really mean?"

The strengths of the Pacific Northwest Tribes in the negotiations

Roy Sampsel:

"The one thing you can say about the tribal people at the time is that they never blinked. They knew exactly what it meant to them and they knew exactly what the United States was going to have to do. Now, we're still working to try to figure out what that means on any given day and how it still needs to be applied but during those late ‘70s and into the early ‘80s, there was this sort of commitment that we have won this right in the courts and the federal government needs to now step up to the plate to make sure that those rights are able to be implemented and that there is no further erosion."

Roy served as the first Executive Director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission from 1977-1979. The Northwest Indian Fish Commission in Puget Sound had been formed in 1974.

Roy Sampsel:

"I can still remember the meeting in which they asked if I'd be willing to come and be the Executive Director. We were meeting at the Portage Inn up in Dalles and the tribal leadership was up there and our tribal attorneys were involved and I said, ‘Well, let me just think about this for a minute.' And they said, ‘Well, you don't have too much time to think about it cause we've got a lot of work to do.' And so I said, ‘Okay, suppose I said yes, what would my first job be?' They said, ‘Well, you would have to go to Washington, D.C. and get some money cause we have no way to pay you.' And so that was sort of the...kind of the humor if you will about also and the importance of how would you actually put one of these commissions together? The commission in Puget Sound had been operating for a few years and it had gotten started a little bit earlier and we were still wrestling with those issues. Now, in comes the new administration and President Carter wants to try to figure out if they can figure out how to negotiate an agreement, a settlement to the disputes and the court cases in Puget Sound. So while we've started the Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, I'm not its executive director and being asked by the Puget Sound tribes if I will be their lead negotiator in negotiating with the State of Washington and the federal government during the supposed settlement negotiations. It was absolutely a fascinating timeframe. Now, why would a executive director from the Inter-Tribal Fish Commission on the Columbia River be asked to be the negotiator for the Puget Sound tribes? And the reason is because the Yakimas were a party to both cases and saw the need for somebody who they trusted to be a piece of this negotiating team and all of this earlier sort of experience that I'd had doing all these things, there weren't a whole lot of Indian folks that had actually worked in the administration and worked politically and so it was that sort of...all of that background experience now became a useful tool in how could you start to implement a treaty right. And what type of skills would you bring to a negotiating table? Okay, Roy, you can go negotiate but your job is to give away absolutely nothing and the State of Washington had hired a negotiator, a gentleman by the name of Bill Wilkerson. Bill then goes on later in his life to become the Fish and Wildlife Director for the State of Washington. And all of us in those period of times were trying to sit around and figure out how could you craft certain types of agreements that were consistent with what the court had said and consistent with what the tribes wanted and needed in order to be able to implement their treaty right."

Values and strengths on which he drew in these times

Roy Sampsel:

"That's the beauty of grandma and mom and dad who...granny who had that great Indian wisdom, mom and dad who survived the Depression and going to Indian boarding school in the ‘30s. The political teachings of Frank Roberts and all of those folks and so basically the people that had been teaching me how to do specifics had also taught you how to deal with opportunity and controversy and the challenge. The leadership that wouldn't allow you to fear failure or to understand that there was even an option to quit, how could you possible do that with people who hadn't quit in their entire lifetime or in the lifetimes of their parents or their grandparents. This was not something...it was not casual and it wasn't just political, it was very, very significant in terms about the culture and the religion of those people. You could not...you could not not do what was needed. It wasn't allowed. It wasn't an acceptable alternative. So what you didn't know you learned and what you didn't know you created. Blind luck, a lot of it."

Serving as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs under Secretary of the Interior James Watt

Roy Sampsel:

"He was one of the people who probably did more to damage himself than anybody could have done for him. And I say that because he had a sense of what it needed to be, he didn't really understand what it was and he understood that self-determination was really a piece of how you turned Indian reservations and Indian tribes around was the ability to have great economic independence, greater economic independence from the federal government. He didn't quite understand the relationship between the tribal government doing that and what was necessary. And I have known every Secretary of Interior since Stuart Udall who served in the Kennedy administration and without exception most of the Secretaries of Interior have left their position disappointed that they were not able to do more in relationship to their tribal and Indian responsibility and part of that is I think because none of them truly had an understanding of what it would take to implement a trust relationship with tribes. This particular Secretary that we're dealing with now in this administration, Gale Norton, working for the Bush administration inherited a hundred year old failure of federal government to deal honestly with trust assets of individual Indians and tribes. Now, how...can you imagine that happening in any other avenue of society in the United States of America in which you would have 100 year of failing to deal with fiduciary responsibilities associated with dealing with individual Indians and tribal resources, cash, real dollars going to real accounts not being able to be tracked or understood? Gale Norton didn't do that but she is the lady in charge of that department now. So for 100 years Secretaries of Interior in the federal government fail Indian people. And when you get back to an individual Secretary, they each understood pieces of it but never understood it enough to take it seriously as a responsibility to fix the deficiencies which allowed for...Jim Watt speaking about the need to create Indian wealth while his department was managing billions of dollars of Indian monies and not being able to figure out that that was a primary responsibility that he had as Secretary. So pieces of this are still weaving themselves together into a fabric that I think will speak well for where Indians end up at say the mid point of the 21st century."

A perspective on tribes from the future

Roy Sampsel:

"You have to remember the time and schedule that tribes are on are a little bit different than the tribes and schedules that others might be on so they're going to be here for a long time and as many of my Indian friends will tell me, we're not going anywhere. We have our homes, we have our lands, our reservation, we have our homeland that we're...so you can change, society can change, it can change but we're going to still be here. So these sort of fixes that we're talking about will in fact take place. We don't know exactly what the picture of Indian America will look like another 50 years from now but I will tell you there will be an Indian America and the picture will be brighter than it is today, perhaps even superior to other societies that have failed to live with both their culture and their religion and their beliefs."

Leadership in Indian Country and the examples of the late Joe de la Cruz (Quinault) and Lucy Covington (Colville)

Roy Sampsel:

"I think Indian leadership will be enhanced by understanding that there have been previous great Indian leaders and that the ability to see that may encourage people to pursue it. I guess I would say the same thing about...Indian leadership is part of a tribal political process as well as a cultural process and if you're well grounded in your roots and the culture and the history of your people and your tribe, then you have to make a decision about whether or not the politics of it is something that you want to pursue and endure. What makes a great United States Senator? I would be hard to draw that profile. What makes a great President? Maybe the fact that he or she was a great Senator or a great Congressman or a good Governor or maybe it's just the events in which they find themselves and how they respond to the crisis of the moment. Would Lucy Covington have such an important place in my sense of history if she hadn't jumped off that tractor as a farmer in Colville and decided there was no way they were going to terminate her tribe? I don't know. If they hadn't been trying to terminate her tribe, would she have jumped off the tractor? So when you start looking at pieces of this, part of it is events and part of it is the fact that there is this sense of responsibility. And I don't know how an individual tribe or an individual person emerges to take on that level of responsibility but it's a personal thing. It's something that they are willing and want to do. Joe de la Cruz who was...there was never a meeting that Joe de la Cruz wasn't willing to go to. He was willing to participate at all levels because he was in some sense afraid not to for fear of what might happen if there wasn't that presence there. But I don't think there is an easy way to say, ‘What is...why did certain tribes have great leaders at this moment?' Well, they may have had spectacular leaders 200 years ago and we just don't know about it."

Tribes and Washington, D.C. politics in late 2002

Roy Sampsel:

"I don't see this administration being in a position or having as a priority great changes that would increase dollars and wealth to Indian Country and Indian tribes. Nor do I see it in a position in which it would be advocating additional resources for natural resources types of issues that Indian tribes are concerned about. I think the greatest sense that I see about Indian tribes and this particular Congress that's coming up and with this administration is that you have the growth of Native American caucuses in both the House and the Senate who are increasing in membership and are bipartisan. Now, that tells me that there is an understanding that the federal trust responsibility to Indian tribes and that special relationship is better understood now than it has been in the past and it is bipartisan in nature, not partisan in nature. I don't know of a Democratic or Republican way to improve Indian housing, to improve Indian health services delivery. There are ways in which it can be done but for the most part it's pretty well understood that those are responsibilities that need to be met. Now will the resources be there? More likely when you have greater money and you probably get a better response out of Democratic Congresses more than Republican Congresses but we'll have to wait and see. I don't see a major change coming about because there is a party in charge of all three. I'm encouraged by the fact that we see a bipartisan approach coming out of both the House and the Senate, Native American caucuses and I think that will have an influence on the budgeting that the President puts forth in future budgets. I think that I am more concerned about the Supreme Court now than I have been but anybody that's been tracking Indian affairs over the last number of years have been concerned about the Supreme Court for the last decade and a half and unless there is a legislative redefinition of federal responsibility and as a result of that the Congress defining the rights and responsibilities of Indian governments, I see continued erosion of that, regardless of which court is in there. But I don't see anything happening positive with this Court now or in the immediate future."

The changes in Indian Country and what's ahead

Roy Sampsel:

"A couple of these may surprise you. I think there are more people willing to say they are Indian now than there were 30 years ago. I think there is a greater personal pride in being an Indian person. There is I think a greater sense that...from the general population that Indians may have a unique wisdom that maybe wasn't appreciated as much 30 or 35 years ago as it is now and that the logic of taking care of the land and the water and the, if you will the cultural and religious significance of that Indian people is having a rebirth in non-Indian thought and pattern. I think that individual Indian entrepreneurship growth in terms of economic self sufficiency and development is what's going to be the most exciting thing to observe over the next couple of decades."

Roy has a reputation for goodwill and generosity: his comments

Roy Sampsel:

"It doesn't have to be big, it just has to be real. You've really got to care that this individual or this action or that type of activity will in some way be of value to something beyond what is now and certainly beyond who you are, that it isn't enough just to be right and to give the speech, it has to work and has to work over time and that requires the persistence and the diligence to make change happen."

The Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times series and accompanying curricula are for the educational programs of tribes, schools and colleges. For usage authorization, to place an order or for further information, call or write Institute for Tribal Government – PA, Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon, 97207-0751. Telephone: 503-725-9000. Email: tribalgov@pdx.edu.

[Native music]

The Institute for Tribal Government is directed by a Policy Board of 23 tribal leaders,

Hon. Kathryn Harrison (Grand Ronde) leads the Great Tribal Leaders project and is assisted by former Congresswoman Elizabeth Furse, Director and Kay Reid, Oral Historian

Videotaping and Video Assistance

Chuck Hudson, Jeremy Fivecrows and John Platt of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission

Editing

Green Fire Productions

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times is also supported by the non-profit Tribal Leadership Forum, and by grants from:

Spirit Mountain Community Fund

Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs

Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, Chickasaw Nation

Coeur d'Alene Tribe

Delaware Nation of Oklahoma

Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe

Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians

Jayne Fawcett, Ambassador

Mohegan Tribal Council

And other tribal governments

Support has also been received from:

Portland State University

Qwest Foundation

Pendleton Woolen Mills

The U.S. Dept. of Education

The Administration for Native Americans

Bonneville Power Administration

And the U.S. Dept. of Defense

This program is not to be reproduced without the express written permission of the Institute for Tribal Government

© 2004 The Institute for Tribal Government