Indigenous Governance Database

fishing rights

UN 2023 Water Conference: Restoring Rivers, Restoring Sovereignty: Klamath River Dam Removals

A discussion about the impacts of the Klamath River Dams on water resources, cultural practices, climate change and what the upcoming dam removals will mean for Northern California Tribal Nations. Speakers: Shannon Holsey, President, Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians, Treasurer, NCAI…

The Klamath River Now Has the Legal Rights of a Person

This summer, the Yurok Tribe declared rights of personhood for the Klamath River — likely the first to do so for a river in North America. A concept previously restricted to humans (and corporations), “rights of personhood” means, most simply, that an individual or entity has rights, and they’re…

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: Billy Frank, Jr.

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the "Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times" interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary tribal leaders who have been active in the struggle for tribal sovereignty, self-determination, and treaty…

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: Mike Williams

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-…

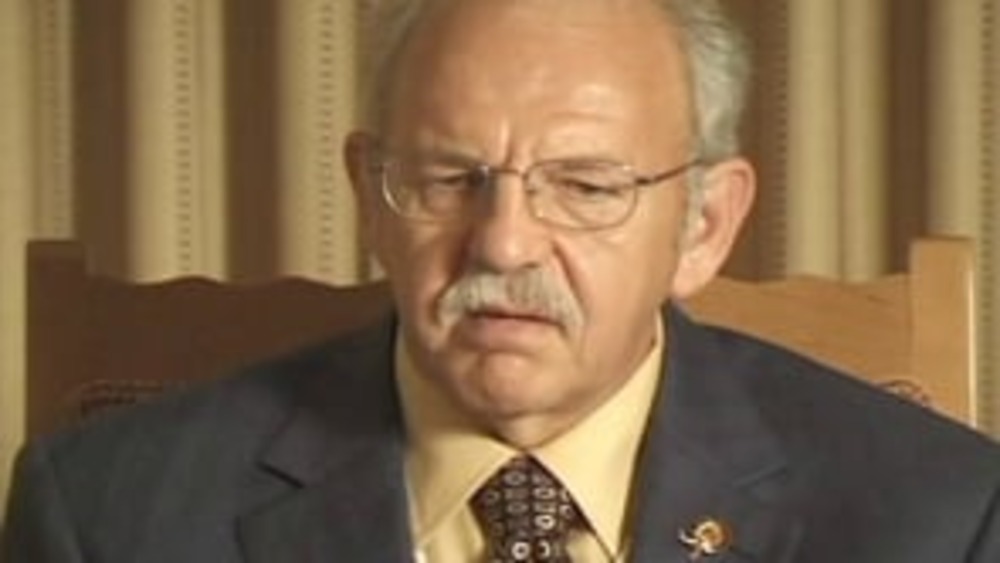

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: Roy Sampsel

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-…

Terrance Paul: Building Sustainable Economies: Membertou First Nation

Chief Terrance Paul shares the keys to a sustainable economy through examples from the Membertou First Nation.

Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times: W. Ron Allen

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University in 2004, the landmark “Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times” interview series presents the oral histories of contemporary leaders who have played instrumental roles in Native nations' struggles for sovereignty, self-…

Klamath Agreements Strengthen Tribal Sovereignty

From time immemorial, salmon, steelhead and other fish runs have sustained the Klamath, Modoc and Yahooskin Paiute members of the Klamath Tribes. It has been more than 100 years, however, since our tribal members have seen salmon and steelhead migrate home to the Upper Klamath Basin, or had an…

Billy Frank Jr.: A World Treasure (1931- 2014)

“I was the go-to-jail guy.” That’s how Billy Frank, Jr., (Nisqually) often described his role during the treaty fishing rights struggle in the Pacific Northwest of the 1960s and ‘70s. Beginning as a teenager of 14, he went to jail more than 50 times and was arrested more than three times that. His…

Tribal Rights Legend and Leader Billy Frank Jr. Walks On

In 2004, we celebrated 30 years since the Boldt Decision of 1974, the landmark Indian fishing rights victory, that Billy Frank Jr. fought so hard for.“Frank is widely credited as conscience and soul of the efforts by Indian people in Washington to secure their rights to a fair share of fish on…

Nooksack Tribe Cites "Missing Ancestor" As Reason To Disenroll 306 Members

In Part Two of the KUOW story documenting the disenrollment of approximately 300 members from the Nooksack Tribe, Liz Jones takes a closer look at the Nooksack's process to disenroll members.

The Ways: Lake Superior Whitefish: Carrying on a Family Tradition

The Petersons are part of a long tradition of commercial fishing among Lake Superior tribes. Avid fishermen for subsistence prior to European settlement, the Lake Superior Chippewa quickly found Gichigami’s (Ojibwe word for Lake Superior) fish to be a valued trade item once explorers penetrated to…

Mi'gmaq Nation Listuguj

The Listuguj Mi'gmaq Listuguj Nation started a movement to protect their salmon fisheries involving protests, arrests, and eventually organizing to establish fishery laws in eastern Quebec. They formalized documents and laws to assert their jurisdiction that began at a grass-roots level in the…