Indigenous Governance Database

Indian Reorganization Act (IRA)

Ian Record: Setting the Focus and Providing the Context: Critical Constitutional Reform Tasks (Presentation Highlight)

In this highlight from the presentation "The Process of Constitutional Reform: The Challenge of Citizen Engagement," NNI's Ian Record lays out two critical overarching tasks that those charged with leading a nation's constitutional reform effort must undertake.

Honoring Nations: Cedric Kuwaninvaya: The Hopi Land Team

Former Chairman of the Hopi Land Team Cedric Kuwaninvaya presents an overview of the tribal subcommittee's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Gerald Clarke, Jr.: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Cahuilla Band of Indians Council Member Gerald Clarke, Jr. shares his thoughts about what he wished he knew before taking office as an elected leader of his nation.

John "Rocky" Barrett: A Sovereignty "Audit": A History of Citizen Potawatomi Nation Governance

Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman John "Rocky" Barrett shares the history of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and discusses its 40-year effort to strengthen its governance system in order to achieve its goals.

Erma Vizenor: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change: The White Earth Nation Story

White Earth Nation Chairwoman Erma Vizenor discusses some of the historical factors that eventually compelled her and her nation to undertake constitutional reform, and the issues her nation has encountered as they work to ratify a new constitution and governance system.

Ben Nuvamsa: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Former Chairman of the Hopi Tribe Ben Nuvamsa speaks about his tenure as the elected chief executive of his nation, and how the governance issues he and his nation have experienced in recent years offer important lessons to other Native nations.

David Wilkins: Patterns in American Indian Constitutions

University of Minnesota American Indian Studies Professor David Wilkins provides a comprehensive overview of the resiliency of traditional governance systems among Native nations in the period leading up to the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), and shares some data about the types of…

Greg Gilham: Engaging the Nation's Citizens and Effecting Change: The Blackfeet Nation Story

Greg Gilham, Former Chair of the Blackfeet Nation's Constitution Reform Committee, discusses the process the committee developed to move constitutional reform forward.

Honoring Nations: Sovereignty Today: Q&A

The 2007 Honoring Nations symposium "Sovereignty Today" panel presenters as well as members of the Honoring Nations Board of Governors field questions from the audience and offer their thoughts on the state of tribal sovereignty today and the challenges that lie ahead.

Native Nation Building TV: "Moving Towards Nation Building"

Manley A. Begay, Jr. and Stephen Cornell contrast the two basic approaches to Indigenous governance -- the standard approach and the nation-building approach -- and discusses how a growing number of Native nations are moving towards nation building. It provides specific examples of how implementing…

Joan Timeche and Joseph P. Kalt: The Process of Constitutional Reform: Key Issues and Cases to Consider

Joan Timeche and Joseph P. Kalt share two stories of constitutional reform processes undertaken by Native nations and discuss what factors spurred or impeded the ultimate success of those efforts.

Native Nation Building TV: "Constitutions and Constitutional Reform"

Guests Joseph P. Kalt and Sophie Pierre explore the evidence that strong Native nations require strong foundations, which necessarily require the development of effective, internally created constitutions (whether written or unwritten). It examines the impacts a constitution has on the people it…

Todd Hembree: A Key Constitutional Issue: Separations of Powers

Cherokee Nation Attorney General Todd Hembree discusses the critical role of separations of powers in effective Native nation governance, and provides an overview of how the Cherokee Nation instituted an array of separations of powers in the development of their new constitution, which was ratified…

Frank Pommersheim: A Key Constitutional Issue: Dispute Resolution (Q&A)

University of South Dakota Professor of Law Frank Pommersheim fields audience questions about the importance of civic engagement to constitutional reform, removing the Secretary of Interior Approval clause from tribal constitutions, and other important topics.

Teach youth about forms of government

Why aren’t the schools teaching about the IRA form of government? Why aren’t they teaching about the traditional tiospaye form of government? The disenchantment and what appears to be apathy or even seditiousness toward the Indian Reorganization Act system of government have become “normal” among…

Red Lake Constitutional Reform Informational Meetings Held

The meeting at Bemidji was one leg of the second round of informational meetings conducted by the Red Lake Constitutional Reform Committee (CRC) in order to seek input and feedback from the membership regarding Constitutional Reform. Meetings are held in Duluth and the Twin Cites in addition to the…

Red Lake Constitution Reform Initiative Community Engagement Meeting held in Redby

The second of six scheduled Red Lake Constitution Reform Initiative Community Engagement Meetings was held at the Redby Community Center on March 24, 2014 from 5:30 PM to 8:30 PM. The first meeting was held at the Minneapolis American Indian Center on March 22, 2014 with about 60 people in…

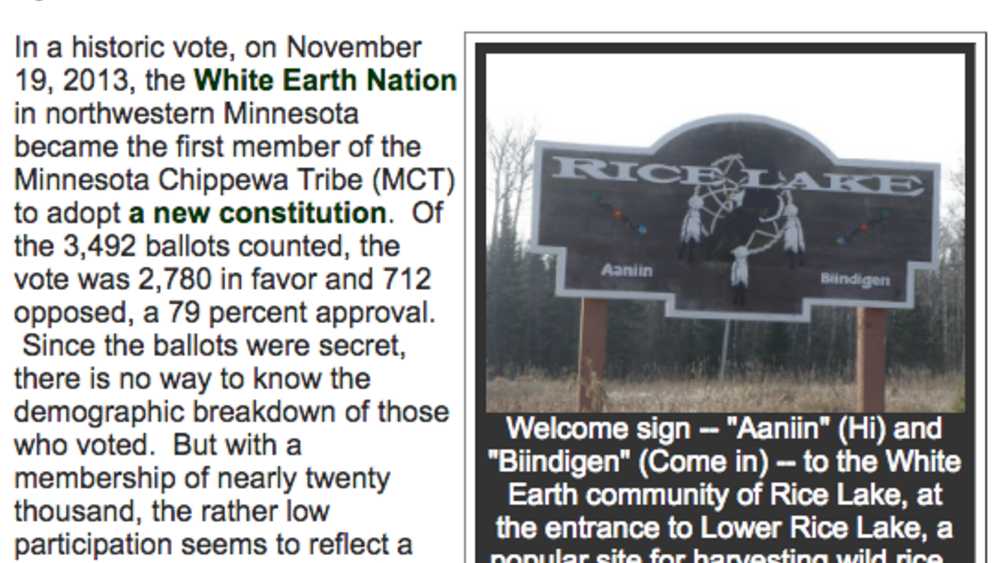

White Earth Nation Adopts New Constitution

In a historic vote, on November 19, 2013, the White Earth Nation in northwestern Minnesota became the first member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe (MCT) to adopt a new constitution. Of the 3,492 ballots counted, the vote was 2,780 in favor and 712 opposed, a 79 percent approval. Since the ballots…

Indigenous Nations Have the Right to Choose: Renewal or Contract

When making significant change Indigenous nations make choices about whether to build on traditions or to adopt new forms of government, economy, culture or community. Many changes are external and often forced upon contemporary Indigenous Peoples. Adapting to competitive markets, or new…

How Does Tribal Leadership Compare to Parliamentary Leadership?

Many traditional American Indian governments have significant organizational similarities with contemporary parliamentary governments around the world. A key similarity is that leadership serves only as long as there is supporting political consensus or confidence that the leader or leadership…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- Last page