Indigenous Governance Database

traditional governance systems

Michael K. Mitchell: A History of the Akwesasne Mohawk

Grand Chief Michael Mitchell of the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne offers students a broad overview of the governance history of the Akwesasne Mohawk and the efforts his people have made during his time in office to exercise true self-governance and rebuild their nation.

Oren Lyons: Looking Toward the Seventh Generation

Onondaga Chief and Faithkeeper Oren Lyons discusses the increasingly urgent issues of global warming and climate change and points to Indigenous peoples, their core values, and their reciprocal relationships to the natural world as sources of instruction for human beings to heed in order to combat…

Ben Nuvamsa: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Former Chairman of the Hopi Tribe Ben Nuvamsa speaks about his tenure as the elected chief executive of his nation, and how the governance issues he and his nation have experienced in recent years offer important lessons to other Native nations.

Darrin Old Coyote: Reforming the Apsaalooke (Crow) Nation's Governing System: What Did We Do and Why Did We Do It?

Vice Secretary Darrin Old Coyote of the Crow Tribe's Executive Branch provides a brief history of the Crow Tribe's governance system, and explains the factors that prompted the Tribe to abandon its governance system in 2001 and replace it with a new constitution and system of government…

Stephen Cornell: Getting Practical: Constitutional Issues Facing Native Nations

Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy Director Stephen Cornell provides a brief overview of what a constitution fundamentally is, and some of the emerging trends in innovation that Native nations are exhibiting when it comes to constitutional development and reform. This video resource is…

David Wilkins: Patterns in American Indian Constitutions

University of Minnesota American Indian Studies Professor David Wilkins provides a comprehensive overview of the resiliency of traditional governance systems among Native nations in the period leading up to the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), and shares some data about the types of…

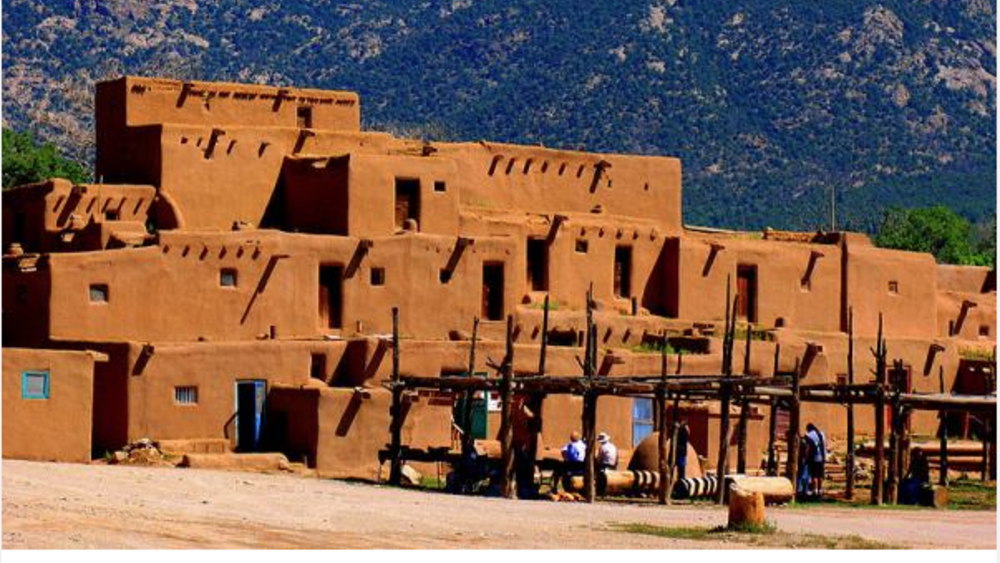

Regis Pecos: The Role of Core Values in Cochiti Governance and Renewal

In this excerpted video, former Cochiti Governor Regis Pecos provides an overview of the core values that are integral to Cochiti's culture and way of life, and shows how his people relied on the application of those core values to overcome a catastrophe and rebuild its nation and community. This…

Michael K. Mitchell: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Mohawk Council of Akwesasne Grand Chief Michael K. Mitchell reflects on his role as a modern elected leader of his nation. Mitchell encourages small changes in terminology and ideology that in turn will change the community's mindset about nation rebuilding and what is possible.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Justice Systems and Cultural Match"

Professor Robert A. Williams, Jr. argues that Native nations can reintegrate their unique cultures and common law into their governance systems, specifically their systems for resolving disputes and providing justice to their citizens and others.

Regis Pecos: The Why of Making and Remaking Governing Systems

Former Cochiti Pueblo Governor Regis Pecos shares his thoughts about the ultimate purpose of constitutions, governments and governance from a Pueblo perspective, and argues that constitutional reform presents Native nations with a precious opportunity to reclaim and reinvigorate their cultures and…

How Do We Re-Member?

On July 2, the tribal council of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde held a special meeting to allow their citizens an opportunity to testify for or against a proposed emergency enrollment ordinance whereby the Council sought to delegate its constitutional authority to involuntarily…

Red Lake Constitutional Reform Informational Meetings Held

The meeting at Bemidji was one leg of the second round of informational meetings conducted by the Red Lake Constitutional Reform Committee (CRC) in order to seek input and feedback from the membership regarding Constitutional Reform. Meetings are held in Duluth and the Twin Cites in addition to the…

As old ways faded on reservations, tribal power shifted

Long before the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act transformed tribal government, before nepotism and retaliation became plagues upon reservation life, there were nacas. Headsmen, the Lakota and Dakota called them. Men designated from their tiospayes, or extended families, to represent their clans…

A Lifetime Journey: Alabama-Coushatta Name New Chiefs

For the first time in nearly two decades, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas is welcoming a new principal and second chief. The 1,200-member tribe, located on 4,500 acres of land north of Houston, elects its chiefs to life terms. An inauguration ceremony held January 1 was the first such event…

Back to Our Path is not a Trip Backward

Many of us are familiar with our expression Ohnkwe Ohnwe. It is what we use to describe ourselves as the original people of Turtle Island. The approximate translation is “real human being, forever.” There was never any question that we had a future. We were never tied to a spot on a timeline. We…

Stirring the Ashes

One of the biggest challenges for any people is broad participation in the issues that affect everyone. And when you stop and think about it, there is very little from the smallest ripples in a family to major calamities in a community that occurs without impacting others. The notion of “mind your…

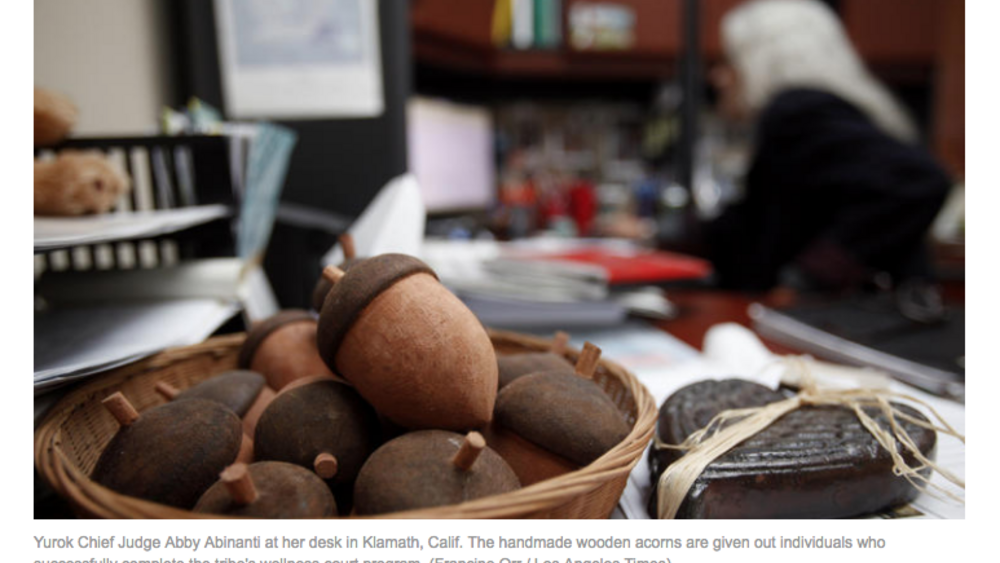

Yurok tribe's wellness court heals with tradition

Lauren Alvarado states it simply: “Meth is everywhere in Indian country.” Like many here, she first tried methamphetamine at age 12. Legal trouble came at 13 with an arrest for public intoxication. In the years that followed, she relied on charm and manipulation to get by, letting her grandmother…

Indigenous Nations Have the Right to Choose: Renewal or Contract

When making significant change Indigenous nations make choices about whether to build on traditions or to adopt new forms of government, economy, culture or community. Many changes are external and often forced upon contemporary Indigenous Peoples. Adapting to competitive markets, or new…

How Does Tribal Leadership Compare to Parliamentary Leadership?

Many traditional American Indian governments have significant organizational similarities with contemporary parliamentary governments around the world. A key similarity is that leadership serves only as long as there is supporting political consensus or confidence that the leader or leadership…

Indian Pride: Episode 112: Tribal Government Structure

This episode of the "Indian Pride" television series, aired in 2007, chronicles the governance structures of several Native nations in an effort to show the diversity of governance systems across Indian Country. It also features an interview with then-chairman Harold "Gus" Frank of the…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- Last page