Indigenous Governance Database

Hopi Tribe

Hopi Farm Talk Podcast: Indigenous Foods Knowledges Network Gathering with Mary Beth Jäger

On September 12-16, 2022, the Natwani Coalition & Hopi Foundation hosted the Indigenous Foods Knowledges Network (IFKN) on Hopi Territory. This historic gathering connected Indigenous communities from Alaska and the Southwest in spaces provided for a sharing of knowledge. Tribal food and data…

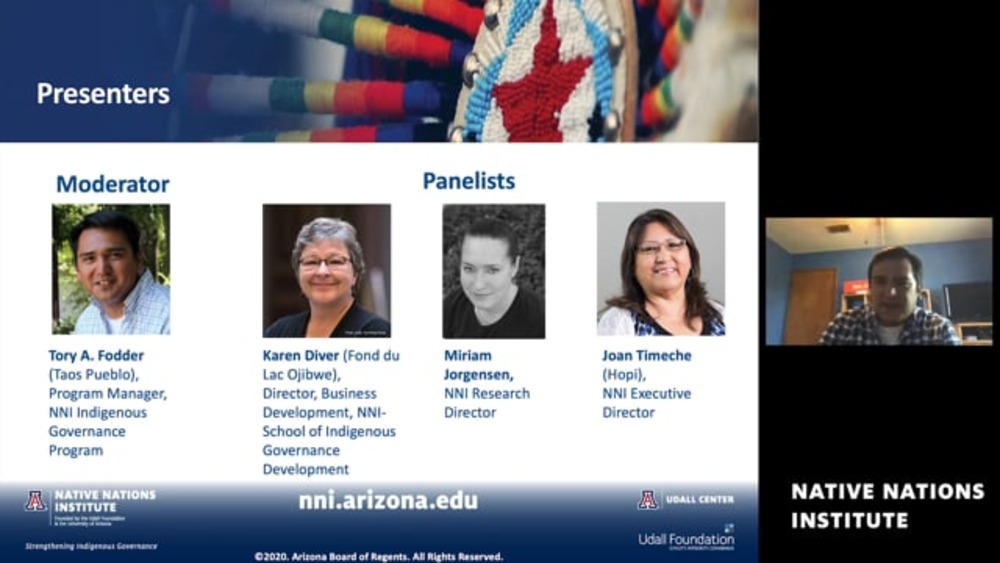

Webinar: Rebuilding Native Nations and Strategies for Governance and Development

The Indigenous Governance Program (IGP) at the University of Arizona has long been at the vanguard of delivering Indigenous Governance Education. To do our part at this critical time, IGP was pleased to offer our January in Tucson Courses in May event free of charge, live streamed via Zoom to…

Vernon Masayesva: Self-Governance and Protecting Water

Former Tribal Chairman of the Hopi Nation and Executive Director of Black Mesa Trust, Vernon Masayesva relays his thoughts about advocating for self-governance and protection of water rights for Indigenous people. His pursuits in holding accountability of mining in Hopi territory has made Vernon…

Vernon Masayesva Keynote: Water Ethics Symposium

Vernon Masayesva (Hopi) is the Executive Director of Black Mesa Trust and leading advocate for protecting water resources for the Hopi Nation. He's a Hopi Leader of the Coyote Clan and former Chairman of the Hopi Tribal Council from the village of Hotevilla who has worked for decades…

Hopi Tribe Constitution

Location: Arizona Population: 19,000 Date of Constitution: 1936

Leroy Shingoitewa: Self-Governance with Hopi Values

Leroy Shingoitewa, member of the bear clan, and served as chairman of the Hopi tribe and since January 2016, has served as a councilman representing the village of Upper Moenkopi. He recalls the intricacies of governing while maintiang Hopi values and traditions.

Hopi Tribe: Governmental Structure Excerpt

ARTICLE III-ORGANIZATION SECTION 1. The Hopi Tribe is a union of self-governing villages sharing common interests and working for the common welfare of all. It consists of the following recognized villages: First Mesa (consolidated villages of Walpi, Shitchumovi, and Tewa). Mishongnovi.…

Hopi Tribe: Preamble Excerpt

Preamble: This Constitution, to be known as the Constitution and By-laws of the Hopi Tribe, is adopted by the self-governing Hopi and Tewa Villages of Arizona to provide a way of working together for peace and agreement between the villages, and of preserving the good things of Hopi life, and to…

A Call to Action

As Native peoples across the country celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Indian occupation of Alcatraz (1969-1971) this fall, many newspapers, magazines and networks are filing stories that attempt to assess both the event's immediate impact as well as its cultural legacy. While many of these…

The Two-Plus-Two-Plus-Two Program: Building an Educational Bridge to the Future for the Youth of the Hopi Tribe from High School to College and Beyond

Over the last 30 years, Native nations across North America have been taking control of their educational systems in the belief that American Indian “self-determination and local control [are] means of cultural preservation and growth.” Disturbed by the low achievement scores…

Hopi Education Endowment Fund

In a pursuit to ensure growth, protect assets, and meet the present and future educational needs of the Hopi Tribe, an ordinance establishing the Hopi Education Endowment Fund was approved. Taking advantage of IRS Code Section 7871 allows for tax deductible contributions made to the Tribe to…

Hopi Jr./Sr. High: Two Plus Two Plus Two

Developed in 1997, the Two Plus Two Plus Two college transition program is a partnership between Hopi Junior/Senior High School, Northland Pioneer College, and Northern Arizona University. The program recruits junior and senior high school students to enroll in classes (including distance learning…

The Hopi Land Team

Reclaiming traditional lands has been a primary concern of the Hopi Tribe for the last century. In 1996, significant land purchases became possible under the terms of a settlement with the United States. The tribal government was faced with the problem of developing a plan for reacquiring lands,…

Hopi Child Care Program

The Hopi Child Care Program assists families in accessing quality care for children of parents pursuing education and those with work demands that keep them away from home. Understanding the importance of early childhood development coupled with the need for culturally appropriate care, Hopi…

Joan Timeche: The Hopi Tribe: Wrestling with the IRA System of Governance (Presentation Highlight)

In this highlight from the presentation "Defining Constitutions and the Movement to Remake Them," Joan Timeche (Hopi) discusses how the Hopi Tribe continues to wrestle with an Indian Reorganization Act constitution and system of governance that runs counter to its traditional, village-based system…

Robert Miller: Creating Sustainable Reservation Economies

In this informative and lively talk, law professor Robert Miller discusses the importance of Native nations building diversified, sustainable reservation economies through the cultivation and support of small businesses owned by their citizens, and offers some strategies for how Native nations can…

Luann Leonard, Stephen Roe Lewis and Walter Phelps: Bridging the Gap: How Native Culture Forges Native Leaders

Luann Leonard (Hopi), Stephen Roe Lewis (Gila River Indian Community), and Walter Phelps (Navajo) discuss how their personal approaches to leadership have been and continue to be informed by their Native nations' distinct cultures and core values and those keepers of the culture in their…

Native Leaders and Scholars: Citizens Versus Members: Some Food for Thought

Native Leaders and scholars discuss the pervasive role that terminology plays in conceptions of Native nation sovereignty and citizenship, comparing and contrasting the terms "member" and "citizen" and discussing the origins of the term "member" in Native nations' definitions of who is to be…

Robert Hershey: The Legal Process of Constitutional Reform

Robert Hershey, Professor of Law and American Indian Studies at the University of Arizona, provides an overview of what Native nations need to consider when it comes to the legal process involved with reforming their constitutions, and dispels some of the misconceptions that people have about the…

Jill Doerfler and Carole Goldberg: Key Things a Constitution Should Address: Who Are We and How Do We Know? (Q&A)

Presenters Jill Doerfler and Carole Goldberg field questions from seminar participants about the various criteria that Native Nations are using to define citizenship, and some of the implications that specific criteria present.