Indigenous Governance Database

Karen Diver

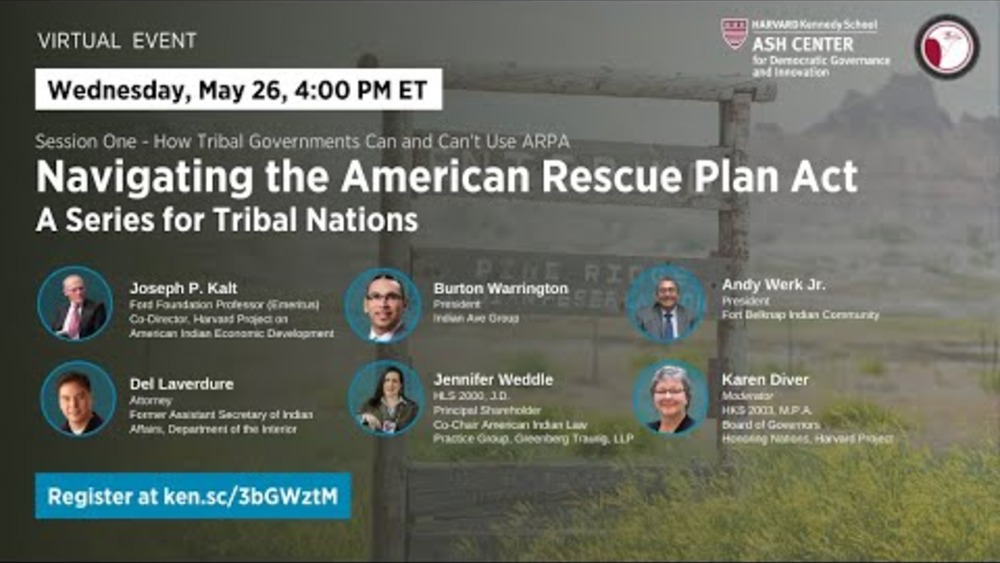

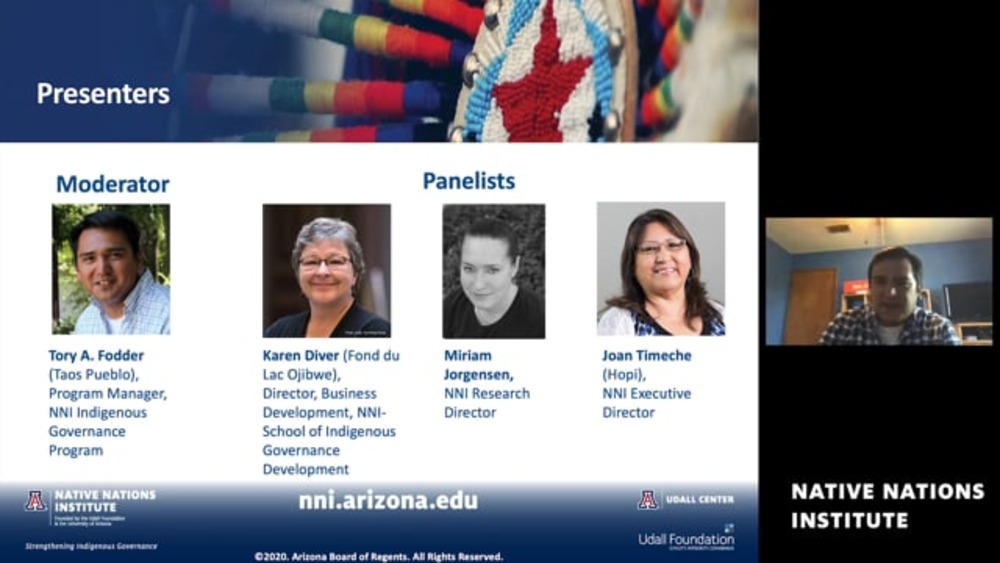

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 1: How Tribal Governments Can and Can't use ARPA

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides the largest single infusion of federal funding into Indian Country in the history of the United States. More than $32 billion is directed toward assisting American Indian nations and communities as they work to end and recover from the devastating COVID-…

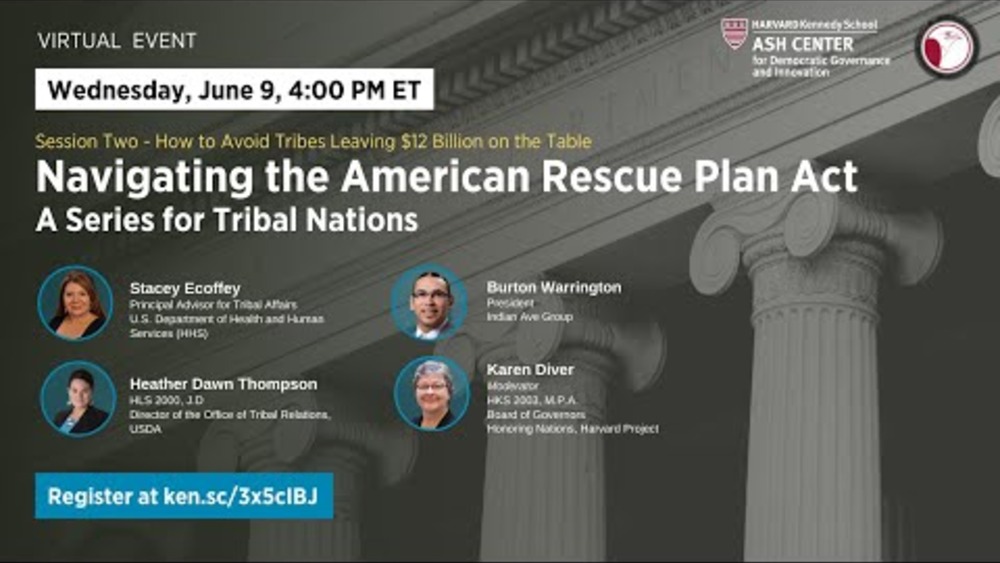

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 2: How Tribes Can Avoid Leaving $12 Billion on the Table

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides the largest single infusion of federal funding into Indian Country in the history of the United States. More than $32 billion is directed toward assisting American Indian nations and communities as they work to end and recover from the devastating COVID-…

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 3: A Conversation with Bryan Newland - How Tribes Can Maximize their American Rescue Plan Opportunities

From setting tribal priorities, to building infrastructure, to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

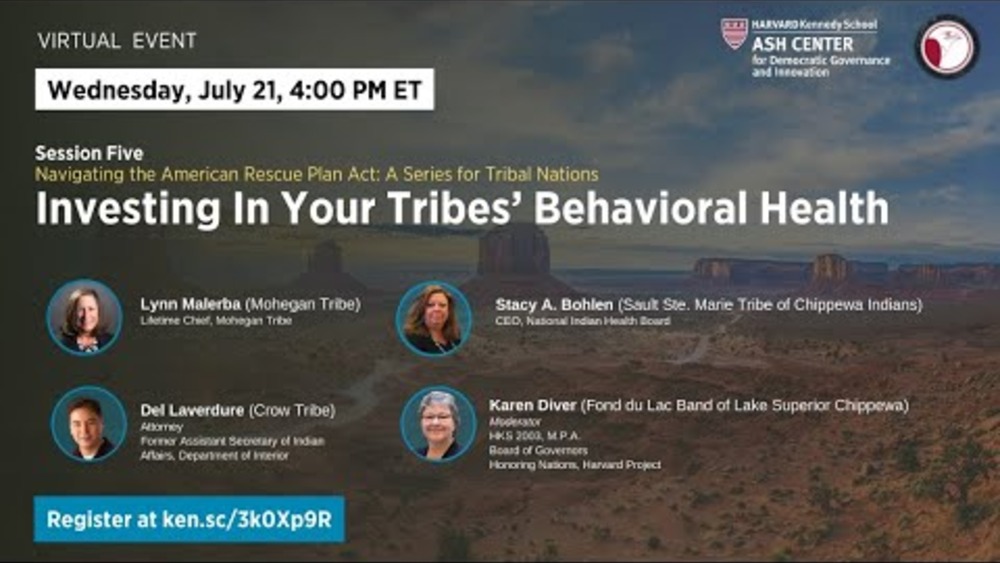

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 5: Investing in Your Tribes' Behavioral Health

From setting tribal priorities, to building infrastructure, to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 6: Investing in Your Tribes' Infrastructure

From setting tribal priorities, to building infrastructure, to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

Navigating the ARPA: A Series for Tribal Nations. Episode 7: Direct Relief for Tribal Citizens: Getting beyond Per Caps

From setting tribal priorities to building infrastructure to managing and sustaining projects, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents an unprecedented opportunity for the 574 federally recognized tribal nations to use their rights of sovereignty and self-government to strengthen their…

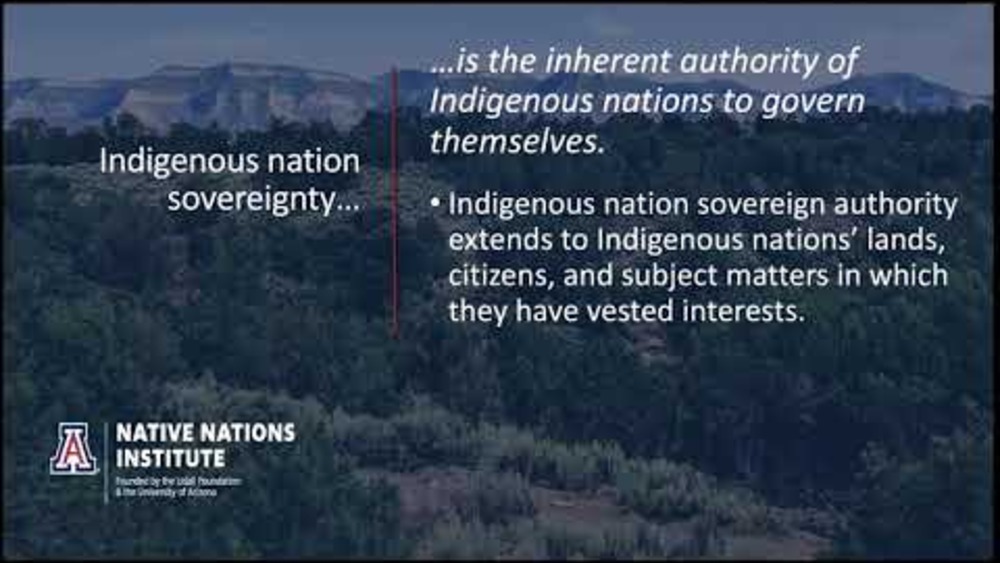

Invisible Borders of Reservations, Tribal Treaties, and Tribal Sovereignty

This 3-part discussion about the invisible borders of reservations, tribal treaties, and tribal sovereignty is led by Dr. Miriam Jorgensen, Research Director of both the University of Arizona Native Nations Institute and its sister organization, the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic…

FEMA's Interagency Recovery Coordination Speakers Series: "Equity, The Foundation of Resilience"

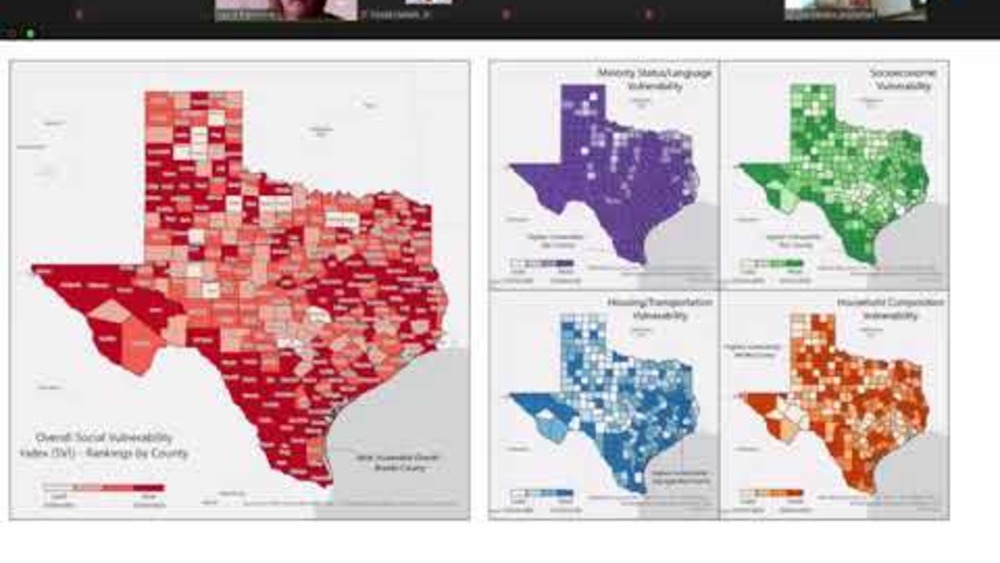

Produced and hosted by FEMA, this 6-part Speaker Series is organized around the theme ‘Equity, Resilience in Recovery’. The goal of the Speaker Series is to bring people together to exchange information, inspire one another, and generate discussion on equitable strategies that build strong…

Bad with Money Podcast: COVID's Economic Devastation on Tribal Lands

Gaby Dunn speaks with Karen R. Diver (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), Director of Business Development for the Native American Advancement Initiatives at the Native Nations Institute and appointee of President Obama as the Special Assistant to the President for Native American Affairs…

Native Nation Building and the CARES Act

On June 10, 2020 the Native Nations Institute hosted an a online panel discussion with Chairman Bryan Newland of the Bay Mills Indian Community, Councilwoman Herminia Frias of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, and hosted by Karen Diver the former Chair of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and…

Webinar: Rebuilding Native Nations and Strategies for Governance and Development

The Indigenous Governance Program (IGP) at the University of Arizona has long been at the vanguard of delivering Indigenous Governance Education. To do our part at this critical time, IGP was pleased to offer our January in Tucson Courses in May event free of charge, live streamed via Zoom to…

Karen Diver: Native leadership and Indigenous governance

Karen Diver is a former Chairwoman of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa and former Vice President of the Minnesota Chippewa tribe, while also served as an adviser to President Obama as his Special Assistant for Native American affairs. Her incredible career as renowned Native…

Dr. Karen Diver: Indigenous autonomy is the way forward

Dr. Karen Diver spoke at ANZSOG's Reimagining Public Administration conference on February 20, as part of a plenary on International perspectives on Indigenous affairs. The Native American tribal leader and former adviser to President Obama, said that Indigenous communities had been inexorably…

Karen Diver: Nation Building Through the Cultivation of Capable People and Governing Institutions

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Chairwoman Karen Diver of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa discusses the critical importance of Native nations' systematic development of its governing institutions and human resource ability to their ability to exercise sovereignty…

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Defending Sovereignty Through Its Effective Exercise"

Native leaders speak to the notion that Native nations' best defense of their sovereignty is the demonstration of their ability to exercise that sovereignty effectively.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Clarifying Roles and Delegating Responsibility"

Native leaders discuss the need for Native nations to define the distinct roles of elected leaders and administrators, and the importance of leaders delegating responsibilities to those appropriately charged with day-to-day administraion.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "The Challenges of Leadership"

Native leaders and scholars discuss some of the many formidable challenges facing leaders of Native nations, from the incredible demands on their time to the vast array of things they need to know and learn.

Honoring Nations: Karen Diver: Sovereignty Today

Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Chairwoman Karen Diver argues that for Native nations to aggressively assert their sovereignty in order to achieve their goals, they must develop capable governing institutions to put that sovereignty into practice.

Native Nation Building TV: "Tribal Service Delivery: Meeting Citizens' Needs"

Guests Eddie Brown and Karen Diver discuss tribal program and service delivery across Indian Country. They examine the unproductive ways services and programs have been administered in many Native communities in the past, and the innovative mechanisms and approaches some Native nations are…

Karen Diver: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office

Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Chairwoman Karen Diver shares her Top-10 list of the things she wished she knew before she took office as chairwoman of her nation, stressing the need for leaders to create capable governance systems and build capable staffs so that they focus on…