Indigenous Governance Database

Citizenship/Membership

Preserving Indigenous Democracy

When Europeans first came to the Americas they took note of the democratic processes they observed in most indigenous nations. Indigenous political relations were usually decentralized, consensus based, and inclusive. Indigenous democracies may not seem remarkable by contemporary standards, but…

Authenticity: Ethnic Indians, non-Indians and Reservation Indians

Authenticity is a puzzling feature of contemporary Indian life. Growing up on an Indian reservation, I rarely encountered challenges to one’s identity as an Indian person. People within the reservation community knew most of the families. If they didn’t know the family connections of a specific…

Building better homes in Indian Country

There's no other house like it on the Oglala Sioux's 2 million-acre Pine Ridge Reservation: Its walls are insulated by 18-inch strawbales rather than plastic sheeting, and its radiant-floor heating is much cheaper than the typical propane or electric. A frost-protected shallow foundation inhibits…

Disenrollment Demands Serious Attention by All Sovereign Nations

For most people, their sense of who they are–their identity–is at least partially defined from connection to others and to a community. When individuals are forced to sever those connections, the consequences can be devastating. Unfortunately, all too often in tribal disenrollment conflicts–like…

Hoka! Coffee gets off the ground in Pine Ridge

Some people are lucky enough to find a job that stimulates their passions, Sharice Davids just happens to be one of those people. Sharice’s recently created a coffee company on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Taking inspiration from the Lakota language she decided to name her company Hoka!…

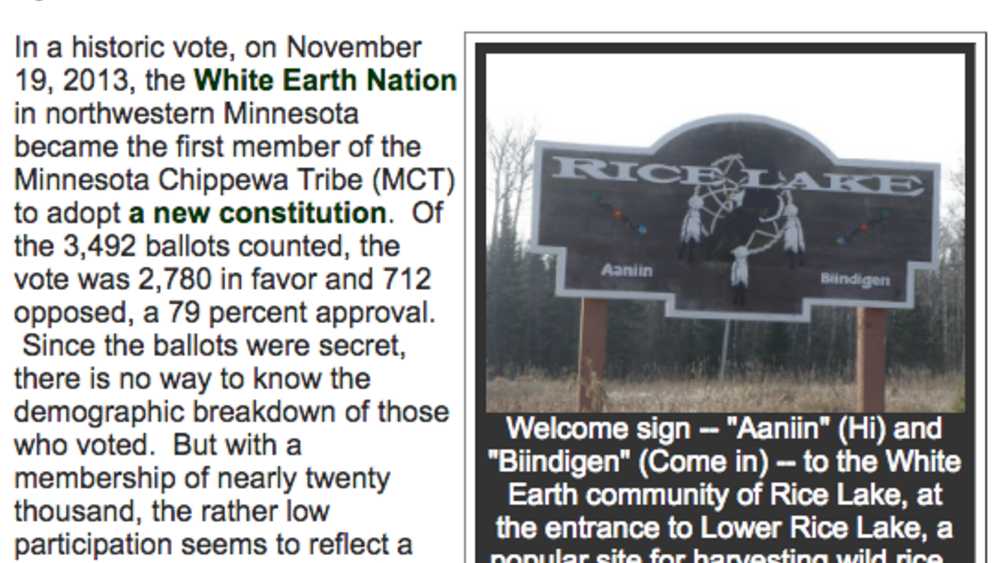

White Earth Nation Adopts New Constitution

In a historic vote, on November 19, 2013, the White Earth Nation in northwestern Minnesota became the first member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe (MCT) to adopt a new constitution. Of the 3,492 ballots counted, the vote was 2,780 in favor and 712 opposed, a 79 percent approval. Since the ballots…

A Better Education for Native Students: The Morongo Method

The Morongo School offers a promising way for Indian nations and communities to educate their children so they have a firm foundation in their own culture, and acquire skills to gain entry and complete college...

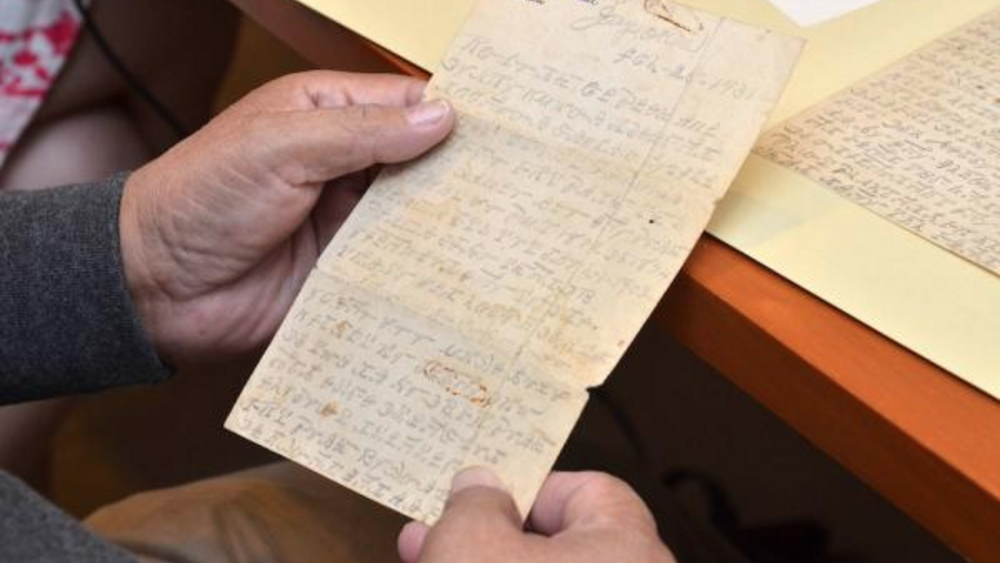

Keeping Language Alive: Cherokee Letters Being Translated for Yale

Century-old journals, political messages and medicinal formulas handwritten in Cherokee and archived at Yale University are being translated for the first time. The Cherokee Nation is among a small few, if not the only tribe, that has a language translation department who contracts with Apple,…

DOJ Grants Muscogee Creek Nation $3.78 Million for Ex-Prisoner Reintegration Program

The Muscogee Creek Nation has received $3.78 million from the U.S. Department of Justice for the tribe’s Reintegration Program (RIP), which assists tribal citizens who have served time in a correctional facility and are ready to be welcomed back into society. The grant will go towards the…

Indian Education Must Support Dual Citizenship, Nation-building

In contemporary nation states education is a key institution for the socialization and creation of citizens. Schools are designed to provide common rules of civic understanding and responsibilities. Students are taught to understand the history, goals, and functioning of government. In many ways,…

How Does Tribal Leadership Compare to Parliamentary Leadership?

Many traditional American Indian governments have significant organizational similarities with contemporary parliamentary governments around the world. A key similarity is that leadership serves only as long as there is supporting political consensus or confidence that the leader or leadership…

Muscogee Creek Nation Meets Growing Pharmacy Needs Through Bilingual, Self-Refill App

A new, automated prescription refill system has made time management much easier for Muscogee Creek pharmacy staff. Nearly a year ago, the tribe tapped Enacomm, a leader in interactive voice response technology, to help the Muscogee Creek Nation Department of Health manage their increasingly high…

Extinct No More: Hia-Ced O'odham Officially Join Tohono O'odham Nation

After 33 years of hard work to right the past, the Hia-Ced O’odham, once thought to be extinct, can finally say they belong as part of the Tohono O’odham Nation. On June 12, the Hia-Ced O’odham District officials were sworn-in and the Hia-Ced District was officially recognized as the 12th district…

What is an Indian?

In the background of all issues involving American Indians is always the question of what is an Indian? While there are any number of groups in this country today who have complicated issues surrounding identity, there is no identity issue more complicated than that of American Indian identity. As…

Blood Quantum: A complicated system that determines tribal membership threatens the future of American Indians

Ryan Padraza Comes Last is a full-blooded Indian, Sioux and Cheyenne on his father's side and Assiniboine on his mother's. He will soon receive his Lakota name: "A Rope." (Comes Last raises rodeo horses and always has a rope in his right hand. He likes to call Ryan his "right-hand man.") But…

Rosebud Sioux Tribe boosts local economy

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe, located in the second poorest country in South Dakota, is making moves to create a way to not only save money for the tribal membership, but also create jobs. "We live in an economically depressed area, so we have to find every small way we can to help people locally,"…

Kin-Based Governments Can Be Successful and Profitable

A key to understanding American Indian nations, and Indigenous Peoples in general, is local community organization. Local groups, as basic building blocks of indigenous nations, play a powerful role in tribal or national consensus building and decision-making. The ways that local indigenous groups…

Where Tribal Justice Works

In 2011, a man in northeastern Oregon beat his girlfriend with a gun, using it like a club to strike her in front of their children. Both were members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. The federal government, which has jurisdiction over major crimes in Indian Country,…

Northern Ute Tribal Enrollment May Rise, Pending Election Could Lower Blood Quantum

A tribal nation with what could be North America’s strictest enrollment criteria may soon decide on more flexible rules that might, if adopted, increase the tribe’s current 3,000-plus membership. A pending election could lower the 5/8 Ute Indian blood degree requirement for membership in the Ute…

Economy, distrust complicate allocation of tribal settlement money

When the Obama administration announced in April that it would pay 41 tribes some $1 billion to settle a lawsuit over federal mismanagement of trust funds, many saw it as a sort of stimulus package for Indian Country -- a chance to invest in long-term development and infrastructure, such as schools…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 5

- 6

- 7

- …

- Last page