Indigenous Governance Database

citizenship

Justice Matters Podcast: (Re)Building Nations with Indigenous Governance | EP 79

On this episode of Justice Matters, co-host Mathias Risse speaks with Megan Minoka Hill, the Senior Director of the Project on Indigenous Governance and Development and the Director of the Honoring Nations program at the Harvard Kennedy School. The Project on Indigenous Governance and…

Wilson Justin: Leadership with Cultural Knowledge and Perseverance

Wilson Justin is a cultural ambassador for Cheesh’na Tribal council and serves as a Vice Chair Board of Directors for Mt. Sanford Tribal Consortium. He relays his expertise and perspective on the intricacies of Indigenous governance in Alaska through adapting cultural traditions, creating a…

Comanche Nation: Citizenship Excerpt

ARTICLE III - MEMBERSHIP Section 1. The membership of the Comanche Nation shall consist of the following: (a) All persons, who received an allotment of land as members of the Comanche Nation under the Act of June 6, 1900 (31 Stat. 672), and subsequent Acts, shall be included as full blood members…

Sarah Deer: The Muscogee (Creek) Nation's Approach to Citizenship

Sarah Deer (Muscogee), Co-Director of the Indian Law Program at the William Mitchell College of Law, provides a brief overview of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's unique approach to defining its citizenship criteria, which essentially creates two classes of citizens: those who run for elected office,…

Jill Doerfler: Defining Citizenship: Blood Quantum vs. Descendancy

Scholar Jill Doerfler (Anishinaabe) talks about the colonial origins of blood quantum as a criterion for determining "Indian" and tribal identity, and explains how the federal government imposed that criterion upon the White Earth people in order to divest them of their land. She also stresses the…

The Unintended Consequences of Disenrollment

For most of the modern tribal self-determination era, American Indian nations have emphasized inclusion. Starting in the early 1970s, higher tribal membership numbers equated to higher federal self-determination dollars. As tribes otherwise redoubled their efforts to reverse the destruction caused…

Disenrollment Is a Tool of the Colonizers

Our elders and spiritual leaders do not teach the practice of disenrollment. In fact, disenrollment is a wholly non-Indian construct. Indeed, when I recently asked Eric Bernando, a Grand Ronde descendant of his tribe’s Treaty Chief and fluent Chinook Wawa speaker, if there was a Chinook Wawa word…

Oglala Sioux Tribe to issue IDs at tournament

For the first time in its history the Oglala Sioux Tribe will bring its enrollment office to the public. During this year’s Lakota Nation Invitational in Rapid City the tribe will have a booth set up to issue tribal IDs to enrolled members who may not have the opportunity to travel to Pine Ridge…

Dismembering Natives: The Violence Done by Citizenship Fights

Outside Indian Country most don't realize that over the past 10 years, several thousand people have had their tribal citizenship status terminated. Most were not dismembered for wrongdoing or adopted by other Native nations. They were simply identified by their elected officials as allegedly no…

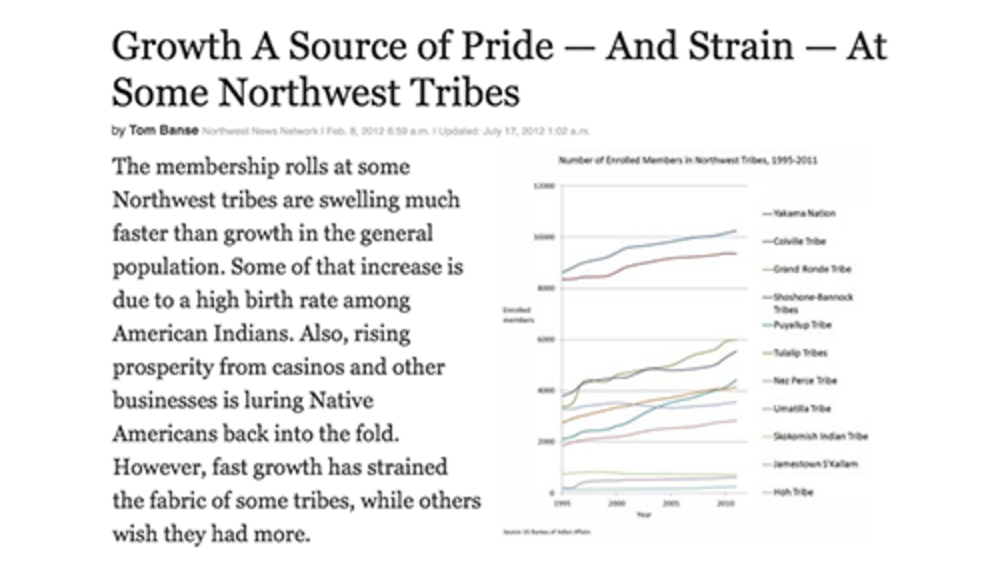

Growth a Source of Pride - And Strain - At Some Northwest Tribes

The membership rolls at some Northwest tribes are swelling much faster than growth in the general population. Some of that increase is due to a high birth rate among American Indians. Also, rising prosperity from casinos and other businesses is luring Native Americans back into the fold. However,…

'We'll Always Be Nooksack': Tribe Questions Ancestry Of Part-Filipino Members

About 300 members from the Nooksack Tribe, near Bellingham, provide their perspective of being disenrolled by Nooksack Tribal Council because of their Nooksack and Filipino ancestry.

Indian Tribes and Human Rights Accountability

In Indian country, the expansion of self-governance, the growth of the gaming industry, and the increasing interdependence of Indian and non-Indian communities have intensified concern about the possible abuse of power by tribal governments. As tribes gain greater political and economic clout on…