Indigenous Governance Database

environmental stewardship

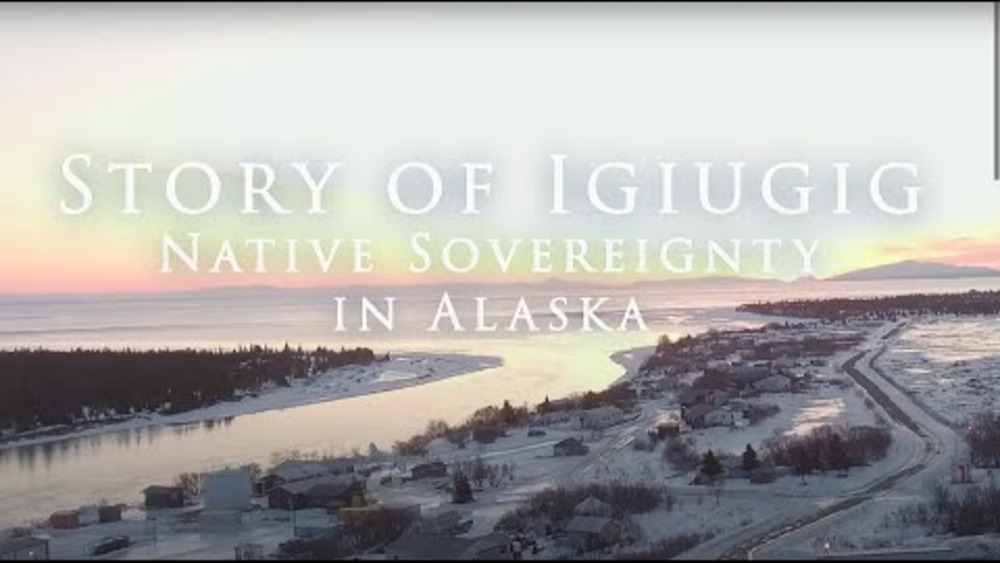

Story of Igiugig: Native Sovereignty in Alaska

This short film looks at how a sovereign Native people are planning for the future, as told through three short chapters: Chapter 1: Nunaput (Our Homelands) Chapter 2: Capricaraq (Persistence) Chapter 3: Pinarqut (Possibility)

Coastal Guardian Watchmen Programs: A Business Case

As the original stewards of their territories, the Coastal First Nations along British Columbia’s North Coast, Central Coast and Haida Gwaii have been working to establish and grow Guardian Watchmen programs, in some cases for several decades. These programs have come to play an important role in…

Coast Salish Gathering

Ecosystems in many parts of North America are under severe stress. Pollution, the overuse of natural resources, and habitat destruction threaten local flora and fauna. Conservation attempts often fall short because they target one species of site within an ecosystem. The Coast Salish Gathering…

Oneida Nation Farms

In the 1820s, a portion of the Oneida people of New York moved to Wisconsin, where they took up their accustomed practices as farmers. Over the next hundred years, the Oneida Nation lost nearly all its lands and much of its own agrarian tradition. In 1978, the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin established…

Bad River Recycling/Solid Waste Department

The Bad River Recycling/Solid Waste Department created environmentally sound practices of managing and disposing of waste generated on the reservation, ending cycles of harm to tribal citizens, lands, and water. Historically, waste was not only hazardous, but noticeable and abundant on reservation…

Honoring Nations: Pat Cornelius: Oneida Nation Farms

Manager of the Oneida Nation Farms Pat Cornelius presents an overview of the organization's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Steve Terry and Rory Feeney: Miccosukee Tribe Section 404 Permitting Program

Miccosukee Tribe Land Resources Manager Steve Terry and Fish and Wildlife Director Rory Feeney present an overview of the Miccosukee Tribe Section 404 Permitting Program to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Cedric Kuwaninvaya: The Hopi Land Team

Former Chairman of the Hopi Land Team Cedric Kuwaninvaya presents an overview of the tribal subcommittee's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Tim Mentz and Loretta Stone: Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Monitors Program

Tim Mentz and Loretta Stone of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Monitors Program present an overview of the program's work to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Pat Sweetsir: Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council

Middle Yukon Representative Pat Sweetsir of the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council (YRITWC) discusses how and why the Indigenous nations living in the Yukon River Watershed decided to establish the YRITWC, and the positive impacts it is having on the health of the watershed and those who…

Honoring Nations: Don Corbine: The Bad River Chippewa Recycling/Solid Waste Department

Former Manager Don Corbine of the Bad River Recycling/Sold Waste Department shares how the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Tribe is using recycling to clean up their community and reinvigorate community pride among its citizens.

Honoring Nations: Jon Waterhouse and Rob Rosenfeld: The Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council

Jon Waterhouse and Rob Rosenfeld provide an overview of the work accomplished by the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Watershed Council, demonstrating the benefits of Native nations who have common cultures and challenges to band together to solve issues of mutual concern.

Wilma Mankiller: Challenges Facing 21st Century Indigenous People

Recorded on October 2, 2008 at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Wilma Mankiller, former principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and internationally known Native rights activist talks about “Challenges Facing 21st Century Indigenous People.†Mankiller talks of the diversity and uniqueness of the over…