Indigenous Governance Database

identity

Carole Goldberg: Designing Tribal Citizenship

Scholar Carole Goldberg shares what she's learned about citizenship criteria from her extensive work with Native nations across the country, and sets forth the internal and external considerations that Native nations need to wrestle with in determining what their citizenship criteria should be.

David Wilkins: Putting the Noose on Tribal Citizenship: Modern Banishment and Disenrollment

The final speaker for the 2008 Vine Deloria, Jr. Distinguished Indigenous Scholars Series at the University of Arizona, scholar David Wilkins (Lumbee) shares his research into the recent and growing phenomenon of disenrollment that is occurring across Indian Country, and delves into the likely…

Wilma Mankiller: What it Means to be an Indigenous Person in the 21st Century: A Cherokee Woman's Perspective

Former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation Wilma Mankiller discusses the common misperceptions that people have about Indigenous people in the 21st century, and the efforts of Indigenous peoples to maintain their identity, cultures, values, and ways of life.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "Constitutions: Reflecting and Enacting Culture and Identity"

Hepsi Barnett, Frank Ettawageshik, Greg Gilham and Donald "Del" Laverdure offer their perspectives on the opportunity that constitutional reform presents Native nations with respect to reintegrating their distinct cultures and identities into their governance systems.

Taylor Keen: The Disenfranchisement of the Cherokee Freedmen: Assertion or Abuse of Sovereignty?

Taylor Keen (Cherokee), a former member of the Cherokee Nation Council, discusses the stand he took against his nation's recent decision to disenfranchise the Cherokee Freedman. He offers a convincing argument against the move, explaining that taking away the citizenship rights of the Freedmen…

Native Language: Pathway to Traditions, Self-Identity

Stacey Burns says a transformation has taken place within the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony from something as old as the Washoe, Paiute and Shoshone tribes themselves: their native languages...

Disenrollment Demands Serious Attention by All Sovereign Nations

For most people, their sense of who they are–their identity–is at least partially defined from connection to others and to a community. When individuals are forced to sever those connections, the consequences can be devastating. Unfortunately, all too often in tribal disenrollment conflicts–like…

Authenticity: Ethnic Indians, non-Indians and Reservation Indians

Authenticity is a puzzling feature of contemporary Indian life. Growing up on an Indian reservation, I rarely encountered challenges to one’s identity as an Indian person. People within the reservation community knew most of the families. If they didn’t know the family connections of a specific…

What is an Indian?

In the background of all issues involving American Indians is always the question of what is an Indian? While there are any number of groups in this country today who have complicated issues surrounding identity, there is no identity issue more complicated than that of American Indian identity. As…

Comanche Nation College Tries to Rescue a Lost Tribal Language

A two-year tribal college in Lawton, Okla., is using technology to reinvigorate the Comanche language before it dies out. Two faculty members from Comanche Nation College and Texas Tech University worked with tribal elders to create a digital archive of what's left of the language. Only about 25…

Two Possible Paths Forward for Native Disenrollees and the Federal Government?

Disenrollment, a seemingly innocuous term when used outside Indian country, has become a loaded word that rivals, if it does not surpass, “termination” as a concept that invokes fear and trembling in those natives who suffer its consequences. While the federal policy of termination in the 1950s was…

Northern Ute Tribal Enrollment May Rise, Pending Election Could Lower Blood Quantum

A tribal nation with what could be North America’s strictest enrollment criteria may soon decide on more flexible rules that might, if adopted, increase the tribe’s current 3,000-plus membership. A pending election could lower the 5/8 Ute Indian blood degree requirement for membership in the Ute…

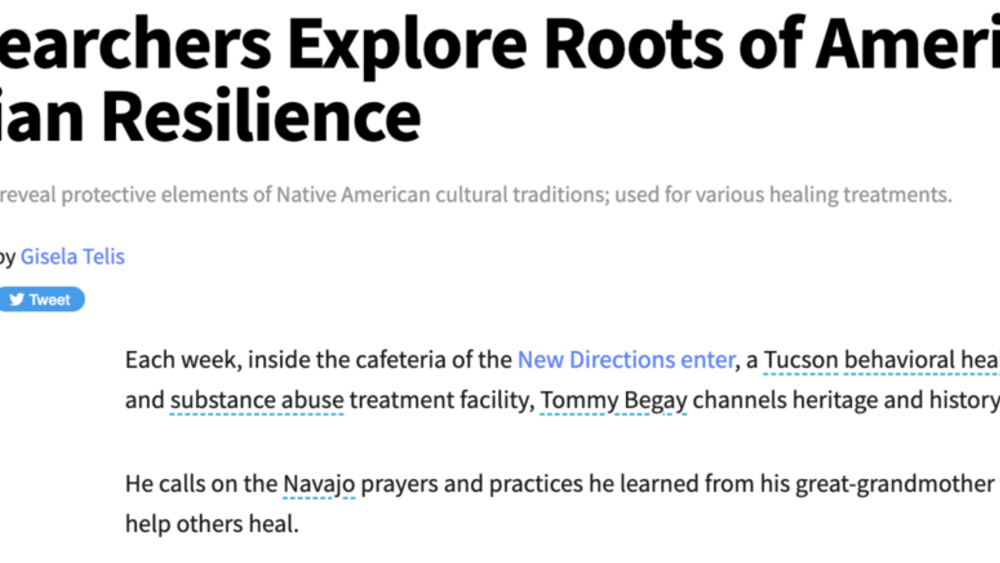

Researchers Explore Roots of American Indian Resilience

Each week, inside the cafeteria of the New Directions enter, a Tucson behavioral health and substance abuse treatment facility, Tommy Begay channels heritage and history. He calls on the Navajo prayers and practices he learned from his great-grandmother to help others heal. “She taught me about…

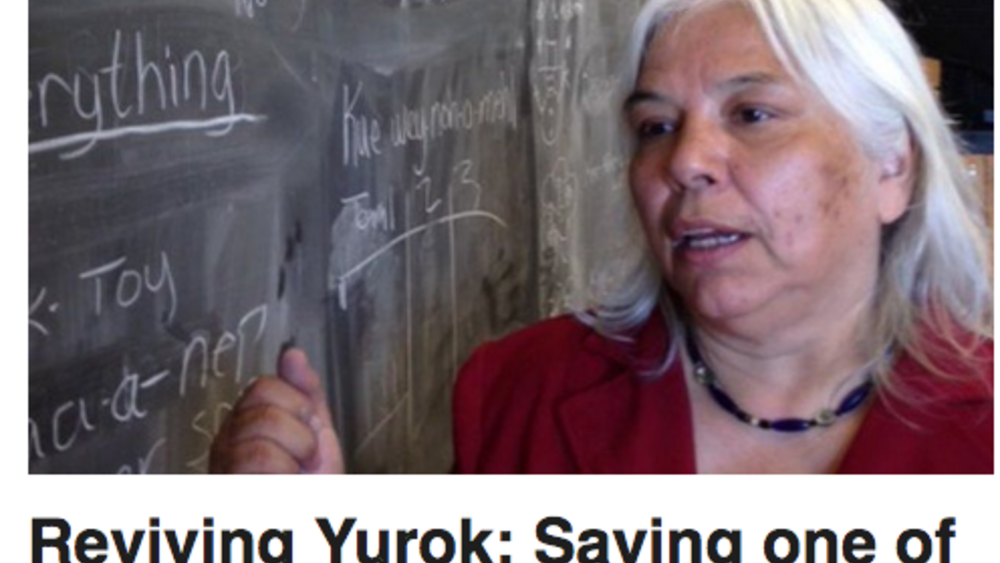

Reviving Yurok: Saving one of California's 90 languages

California is home to the greatest diversity of Native American tribes in the US, and even today, 90 identifiable languages are still spoken there. Many are dying out as the last fluent speakers pass away and English dominates. But one tribe is having success reviving the Yurok language, which was…

Wilma Mankiller: Challenges Facing 21st Century Indigenous People

Recorded on October 2, 2008 at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Wilma Mankiller, former principal chief of the Cherokee Nation and internationally known Native rights activist talks about “Challenges Facing 21st Century Indigenous People.†Mankiller talks of the diversity and uniqueness of the over…

Redefining Tigua Citizenship

The materials in this informational guide are designed to provide you with important background information ”such as Tigua history, tribal population profiles, and fiscal impacts” related to upcoming membership criteria changes. Project Tiwahu is an Ysleta del Sur Pueblo-wide initiative to reclaim…

Understanding the history of tribal enrollment

It's difficult to talk about tribal enrollment without talking about Indian identity. The two issues have become snarled in the twentieth century as the United States government has inserted itself more and more into the internal affairs of Indian nations. Ask who is Indian, and you will get…

Declaration of Tsawwassen Identity & Nationhood

We are Tsawwassen People "People facing the sea", descendants of our ancestors who exercised sovereign authority over our land for thousands of years. Tsawwassen People were governed under the advice and guidance of leaders, highborn women, headmen, and speakers through countless generations...

Navajo Cultural Identity: What can the Navajo Nation bring to the American Indian Identity Discussion Table?

American Indian identity in the twenty-first century has become an engaging topic. Recently, discussions on Ward Churchilla's racial background became a hotbed issue on the national scene. A few Native nations, such as the Pechanga and Isleta Pueblo, have disenrolled members. Scholars such as Circe…

Race and American Indian Tribal Nationhood

This article bridges the gap between the perception and reality of American Indian tribal nation citizenship. The United States and federal Indian law encouraged, and in many instances mandated, Indian nations to adopt race-based tribal citizenship criteria. Even in the rare circumstance where an…

Pagination

- First page

- …

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- Last page