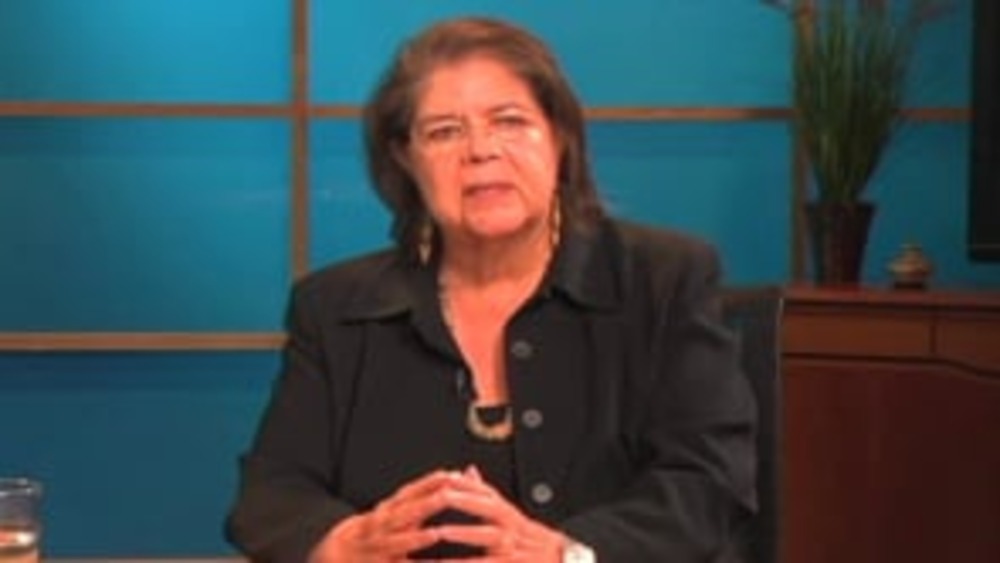

Former Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation Wilma Mankiller discusses the common misperceptions that people have about Indigenous people in the 21st century, and the efforts of Indigenous peoples to maintain their identity, cultures, values, and ways of life.

Additional Information

Mankiller, Wilma. "What it Means to be an Indigenous Person in the 21st Century: A Cherokee Woman's Perspective." Vine Deloria, Jr. Indigenous Scholars Lecture Series, University of Arizona. Tucson, Arizona. September 30, 2008. Presentation.

Transcript

Thank you very much Tsianina [Lomawaima] for inviting me and for working on all the details to get me here. And I also want to thank Teresa wherever Teresa is who’s been in charge of taking care of a lot of logistics and has done a great job. And how I came to be here is that I mentioned to Tom [Holm] one time -- we’re both on this commission that he mentioned -- and I mentioned to him how much I love Arizona. And I told him. ‘If I ever had to live any place other than my home and the Cherokee Nation, I’d live in Arizona.’ And he said, ‘Well, we need to get you to Arizona then.’ And so I also wanted to thank Tom for the invitation to come here today and be with all of you. And I want to thank you. I was just mentioning to Tom how honored I am always when I do public speaking that people would leave their home and their family and their other activities and come to spend an evening just so we can have dialogue together and get to know one another, and I really appreciate that very much and want to express that appreciation to you.

For me it’s an incredible honor to offer remarks about what it means to be an Indigenous person in the 21st century as a part of the Vine Deloria series of events that are occurring here on campus. Many of us who had the privilege of knowing Vine are still trying to figure out how to live in a world without his physical presence and I believe that we can best honor him by doing exactly what this university is doing and that’s continuing to challenge the stereotypes and the misperceptions about Native people that still exist in this country. I also think that we can honor him by getting up every morning and making sure that we stand for something larger than ourselves. I think that’s a way of honoring Vine. And I also think that we can honor him by continuing the fight, his fight, our fight for treaty rights and for tribal sovereignty and also continuing the fight for our cultural survival.

So let me begin by saying that I don’t speak for all Indigenous people or even for all Cherokee people. The thoughts that I share with you tonight are derived entirely from my own experience. And most of my remarks tonight will concern Indigenous people of this country, but I have visited Indigenous people in lots of other places including China. There are very distinct ethnic communities in China, in Ecuador, in South Africa, in New Zealand and in Brazil. There are over 300 million Indigenous people in virtually every region of the world including the Sami peoples of Scandinavia, the Maya of Guatemala, numerous tribal groups in the Amazonian rainforest, the Dalits in the mountains of southern India, the San and Qua in southern Africa, aboriginal people in Australia and of course the hundreds and hundreds of Indigenous people in Mexico, Central and South America as well as here in this land that is now called America. There is enormous diversity among communities of Indigenous people, each of which has its own culture, language, history and unique way of life. Indigenous people across the globe share some common values derived from an understanding that their lives are part of and inseparable from the natural world around them.

Onondaga faith keeper Oren Lyons who spoke here recently once said, ‘Our knowledge is profound and comes from living in one place for untold generations. Our knowledge comes from watching the sun rise in the east and set in the west from the same place over great sections of time. We are as familiar with the land, river and great seas that surround us as we are with the faces of our mothers. Indeed we call the earth [Native language], Our Mother, from which all life springs. This deeply felt sense of interdependence with all other living things fuels a duty and a responsibility to conserve and protect the natural world that is a sacred provider of food, of medicine and spiritual sustenance. Hundreds of seasonal ceremonies are regularly conducted by Indigenous people to express thanksgiving for the gifts of nature and to acknowledge the seasonal changes and to remind people of their obligations to each other and to the earth.’

And the stories continue. In many Indigenous communities around the world, traditional stories embody the collective memory of the people. These stories often describe how things were in the distant past, what happened to cause the world to be as it is today and some stories project far into the future. The prophecies of a number of Indigenous groups predict that the world will end when people are no long capable of protecting nature or restoring its balance. Two of the most widely quoted prophecies are those of the Hopi and the Iroquois, both of which have long predicted that the world will end if human beings forget their responsibilities to the natural world. These prophecies seem particularly important in this era of increasing alarm about the catastrophic effects of climate change and questions, even questions about the long-term survival of humankind. Indigenous people are not the only people on earth who understand that they’re interconnected with all living things. Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore said, ‘At some point during this journey, we lost our feeling of connectedness to the rest of nature. We now dare to wonder, ‘Are we so unique and powerful as to be essentially separate from the earth?’’

There are many thousands of people from different ethnic groups who care deeply about the environment and fight every day to protect the earth. The difference between non-Indigenous environmentalists and Indigenous people who live close to the land is that Indigenous people have the benefit, the unique benefit of having ceremonies that regularly remind them of their responsibilities to each other and their responsibilities to the land. So they remain close to the land not only in the way they live but in their hearts and in the way they view the world.

To me, sometimes when I talk to mainstream environmentalists it’s almost like environmentalism is an intellectual exercise. The difference when you talk to people who, traditional Indigenous people who live close to the land is that they feel that the connection to the land and their responsibility to take care of it is a sacred duty, it’s not an intellectual exercise. When women like Pauline Whitesinger, an elder at Black Mountain or at Big Mountain, and Carrie Dann, a Western Shoshone land rights activist speak of preserving the land for future generations, they’re not talking about just future generations of humans, they are talking literally about future generations of all living things. That’s a profound difference. Pauline and Carrie live with the land and they understand the relative insignificance of human beings in the totality of the universe.

When all human beings, Indigenous people and non-Indigenous people lived closer to the land, there was a greater understanding of the interdependence between humans and the land. Author and feminist Gloria Steinem observes that ‘Once, indeed nearly for all the time that human beings have walked this earth, you and I would have been living very differently in small bands, raising our children together as if each child were our own and migrating with the seasons. There were no nations, no lines drawn in the sand. Instead there were migratory paths and watering places with trade and culture blossoming wherever the paths came together in patterns that spread over the continents like lace.’

So what’s happened in the non-Native world is that there’s an absence of the stories and the ceremonies to remind them, and so they have no memory of that time when they lived very close to the land and were responsible for one another and for the land. They’re not only distant from the land and from themselves, they have little understanding of their place in the world.

I remember one time being, I live in a very rural area at the end of a dirt road within the Cherokee Nation and so very conscious of seasonal changes and of things that are going on in the natural world. And I remember once being in New York City at the magical time of dusk and watching the people. Not a single person on a crowded street in New York City looked at or acknowledged the sunset over the Hudson River or even, I imagine, thought about the gift of another day. It made me wonder how many urban dwellers, millions of urban dwellers go about their lives without ever really seeing or thinking about the miracle of the sun rising in the morning and setting again in the evening.

Aside from a different view of their relationship to the natural world, many of the world’s Indigenous people also share a sometimes fragmented but still very present sense of responsibility for one another. Cooperation has always been necessary for the survival of tribal people and even today in the more traditional communities cooperation takes precedence over competition. It’s really quite miraculous that a sense of sharing and reciprocity continues into the 21st century given the staggering amount of adversity Indigenous people have faced. Within many communities at home and I think in tribal communities around the country the greatest respect, the most respected people are not those who have amassed great material wealth or achieved great personal success. The greatest respect is reserved for those people who help other people, people who understand that as Indigenous people we’re born into a community, a specific tribal group and that our entire lives play themselves out within a set of reciprocal relationships. The people that understand that are the most respected people.

There’s evidence of this sense of reciprocity in some Cherokee traditional communities. My husband Charlie Soap leads a widespread self-help movement among the Cherokee in which low-income volunteers work to build walking trails, community centers, sports complexes, water lines and even houses. This self-help movement, in which everybody gets together and helps each other, taps into the traditional value of cooperation for the sake of the common good.

Besides a connection to the land and this sense of reciprocity, the world’s Indigenous people are also bound by the common experience of being ‘discovered’ and subjected to colonial expansion into their territories that led to the loss of an incalculable number of lives and millions and millions of acres of land and resources. The most basic rights of Indigenous people were disregarded and they were subjected to a series of policies that were designed to assimilate them into colonial society and culture. Too often, the policies resulted in poverty, high infant mortality, rampant unemployment, substance abuse and all its attendant problems.

The stories are shockingly similar all over the world. When I first read Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which chronicled the systematic destruction of an African tribe’s social, cultural and economic structure, it sounded all too familiar. Take the land, discredit the leaders, ridicule the traditional healers, send the children off to distant boarding schools; very familiar story. And then I read a report called The Stolen Generation about aboriginal children in Australia who were forcibly removed from their families and placed in boarding schools.

My own father and my Aunt Sally were taken from my grandfather by the U.S. government and placed in a government boarding school when they were very small, very young. So that story is very familiar to Cherokee people and to tribal people all over the world. Indigenous people everywhere on the planet are connected both by our values and by our oppression.

When contemplating the contemporary challenges and problems faced by Indigenous people worldwide, it’s important to remember that the roots of many contemporary social, economic and political problems can be found in colonial policies and those policies continue today across the globe. In the Amazonian rainforest, Indigenous people are continually battling large scale destruction of their traditional homes in the forest by multi-national mining, oil and timber companies. Some small Amazonian Indigenous communities are on the verge of extinction as the result of the murder of their leaders and the forced dispersal of their members. And to make matters worse, some well-meaning environmentalists who should be natural allies focus almost exclusively on the land and appear not to see or hear the people at all.

When I was in Brazil, one of the people there was quite humorous and he said, ‘There was a time when a lot of famous musicians, American and English musicians, would wear T-shirts that said 'Save the Rainforest.'‘ And he said, ‘You never once saw a T-shirt that said 'Save the People of the Rainforest.'‘ Though the people of the forest, the people who live in the forest and have lived there for thousands of years possess the best knowledge about how to live with and sustain the forest.

When you think about it, of the fact that folks focus on the land and not the people, it’s not surprising really because Indigenous people are not in the consciousness of many, of the people in the larger society. There’s too little accurate information available about us, available in educational institutions, in literature, in films or in the popular culture. I believe that the battle to protect the human and land rights of Indigenous people is made immeasurably more difficult by the fact that so few people know much about either the history or contemporary lives of our people and without any kind of history or cultural context, it’s almost impossible for outsiders to understand Indigenous issues. And the information that is available is often produced by non-Native people; some of which is enormously helpful. Some of the anthropological work has helped tribes restore, some tribal people restore their languages and that sort of thing. So some of the non-Native literature is enormously helpful, but too much of it is written by people who spend 15 minutes in a tribal community, become an expert, and then go out and write a book or produce a film.

So there’s a lot of inaccurate information out there. And the lack of accurate information creates a void, which is often filled with nonsensical stereotypes, which either vilify Indigenous people as troubled descendants of savage peoples on the one hand or they romanticize them as innocent children of nature, spiritual but incapable of higher thought on the other hand. Whether the stereotype romanticizes or vilifies people, it’s still very harmful I believe.

Then the stereotypes about Indigenous women are particularly appalling. While the role of Indigenous women in the family and the community, now and in the past, differs from community to community, women have always played very significant roles in most tribal societies. Yet in the media and in the larger society the power, the strength, the complexity of Indigenous women is rarely acknowledged or rarely recognized.

I believe that these public perceptions of tribal people will change in the future because Indigenous leaders now understand that there is a direct link between public perception and public policy and they understand that they must frame the issues for themselves. If Indigenous people don’t frame the issues for themselves, their opponents most certainly will. In the future, as more Indigenous people become filmmakers, writers, historians, museum curators and journalists, they’ll be able to use a dazzling array of technological tools to tell their own stories in their own voice in their own way.

Once a journalist asked me whether people in the U.S. had trouble accepting the government of the Cherokee Nation during my tenure as principal chief. I was a little surprised by the question. The government of the Cherokee Nation predated the government of the United States and the Cherokee Nation had treaties with other countries before it executed a treaty with one of the first U.S. colonies. So that question really surprised me.

During the colonial era and before, many tribal leaders sent delegations to meet with the Spanish, with the English and French in an effort to protect their lands and rights. And these tribal leaders, they would travel to foreign lands with a trusted interpreter and they took maps that had been painstakingly drawn by hand to show their lands to other heads of state. They also took along gifts, letters and proclamations. And what’s very painful now is to look back in history and see that though the tribal leaders themselves, when they traveled to these other places, thought they were being dealt with as heads of state and as equals, historical records indicate that they were sometimes viewed as objects of curiosity and sometimes a great deal of disdain though they themselves, the tribal leaders, were very earnest.

The journalist with the question about Cherokee government needn’t apologize for her lack of knowledge about tribal governments in the U.S. Many people in the U.S. know very little about us though they’ve been living in our former towns and villages now for hundreds of years.

Again, it’s impossible to even contemplate the contemporary lives or future of Indigenous people without some basic knowledge of tribal history. [I’m going to skip some of this history because you probably know all of this.] Tribal governments in the U.S. exercise their range of sovereign rights and it’s interesting because one of the most common misperceptions in the larger culture is that all tribal governments are the same or even worse that all Indian people are the same or that we speak some kind of common ‘Indian’ language. And so one of the tasks I think we have is to remind people that each tribal government is unique and that different tribal governments exercise their sovereign rights in different ways. And some tribal governments have gaming facilities, some have a number of cooperative agreements with the state governments, other tribal governments believe that we are giving up sovereignty to execute any kind of government with a statement government so they don’t engage in those governments. And there are some governments like the Onondaga that have, do not do any kind of gaming, don’t believe in gaming, and they don’t receive any kind of federal funding at all, none. And so they, and they have their traditional government that they’ve had since the beginning of time. But by and large there are many tribal governments in this country now that have their own judicial systems -- most do -- operate their own police force, they run their own schools, they administer their own clinics and hospitals and operate a wide range of business enterprises and there are now more than two dozen tribally controlled community colleges. And the interesting thing is that all these advancements that tribes have made benefit everybody in the community not just tribal people. And the history and contemporary lives and future of tribal governments is intertwined with that of their neighbors.

And even within there’s a lot of difference between various tribal groups, each of which is very distinct, has its own culture, language and history but even within tribal groups there’s a great deal of diversity. And in our tribe, members of our tribe, the Cherokee tribe, are very stratified socially, economically and culturally. There are several thousand Cherokee people that continue to speak the Cherokee language and live in Cherokee communities in rural northeastern Oklahoma. On the other end of the spectrum, there are enrolled members of the Cherokee Nation who’ve never even visited the Cherokee Nation and so there’s a great deal of stratification in our tribe and I believe in other tribes as well.

Each Indigenous community is unique just as each community in the larger society is unique. Outside our communities, I think too many people view Indigenous people through a very narrow, one-dimensional lens and really we’re very interesting and very complex and we’re certainly multi-dimensional human beings that rarely do people outside of our communities see us in that way.

So what does the future hold for Indigenous people across the globe and what challenges will they face moving further into the 21st century? I think that to see the future of Indigenous people one needs only to look at the past. If we as a people have been able to survive such a staggering loss of land, of rights, of resources and lives, how can I not be optimistic that we will survive whatever challenges lie ahead in the next 100 or even 500 years and that we can project far into the future and still have viable Indigenous communities. If we’ve survived what we’ve survived so far, I’m confident we can survive whatever lies ahead. Without question, the combined efforts of government and various religious groups to eradicate traditional knowledge system has had a profoundly negative impact on the culture as well as the social and economic systems of Indigenous people. But again, if we’ve been able to hold onto our sense of community, our sense of interdependence, our generosity of spirit, our languages, our culture, our ceremonies, our medicine, despite everything, how can I not be optimistic about the future? And though some of the original languages, ceremonies and medicine has been irretrievably lost, the ceremonial fires of many Indigenous people across the globe have survived all the upheaval. Sometimes Indigenous communities after major upheaval and removal have almost had to reinvent themselves as a people but they’ve never given up their sense of responsibility to one another and to the land. It is this sense of interdependence I believe that has sustained tribal people thus far and I believe it will sustain them well into the future.

The world’s changing, but we can adapt to change. Indigenous people know about change and have proven time and time again they can adapt to change. No matter where Native people go in the world, they take with them a strong sense of values, a strong sense of who they are and so they can fully interact with the larger society and participate in the larger society around them but still have a sense of themselves. If you look at some of the people like Vine Deloria, or [N.] Scott Momaday, who won a Pulitzer Prize, or the Chickasaw gentleman, who was an astronaut, or the women who, including Maria Tall Chief, who became prima ballerinas, no matter where those people went they took with them a strong sense of who they are.

One of the things that I remember interviewing for my book LaDonna Harris and one of the things that she said strike me. She said, ‘You know, when I was living in Washington as a Senator’s wife, I did the same thing as other Senate wives did.’ But she said -- it didn’t matter who all was talking to her or what situation she was in -- 'I was Comanche and when, whatever was going on around me, I filtered that through my Comanche values and my sense of who I was. I could live in Washington in a similar house as the other Senate wives and do similar things but I never lost my sense of who I was as a Comanche woman.’ She said, ‘I’ve always hated that term that we live in two worlds.’ She said, ‘My world is that I’m a Comanche woman.’ So it was very interesting and I think a lot of people do that. And for the young people here today that are contemplating careers, it doesn’t matter whether you become a physician or a professor or a lawyer or if you live away from your homelands and can’t participate regularly in ceremonies. You can take with you the knowledge and the values wherever you go.

I believe that one of the great challenges for Indigenous people globally and particularly here in the U.S. will be in the future and now will be to develop practical models to capture, maintain and pass on traditional knowledge system to future generations. When we all lived close to one another, it was easy to pass on the knowledge. Many tribal groups even had people who were designated to remember things. It was their job to remember things and pass them on. But since people are very mobile and the world’s changed so much, we have to come up with new models to capture and maintain the knowledge and pass it on to future generations. There’s nothing in the world, nothing that we can learn anywhere that can replace that solid sense of continuity and knowing that a genuine understanding of traditional knowledge brings. We have to preserve that and we have to pass that on to future generations. There are many communities that are working on discreet aspects of culture such as language or medicine, but in my view it’s the entire system of knowledge that needs to be maintained and not just for Indigenous people but for the world at large.

Perhaps in the future Indigenous people who have an abiding and deeply held belief that all living things are related and interdependent can help policymakers understand how completely irrational it is to destroy the very natural world that sustains all life. Regrettably, in the future the battle for human and land rights will continue but the future does look somewhat better. Last year, after 30 years of advocacy by Indigenous people, the United Nations finally passed a resolution supporting the basic inherent rights of Indigenous people. The resolution by the way was passed over the objections of the United States government. The challenge I think for people working in international work now will be to make sure the provisions of the resolution are honored and the rights of Indigenous people all over the world are indeed protected. And the efforts of tribal governments in this country to take full advantage of the self-governance and self-determination policies of the U.S. government are once again a testament to the fact that Indigenous people simply do better when they have control of their own lives.

In the case of my own people, we’re an example of what happens when you have control and then when you lose control. In the case of the Cherokees, after we were forcibly removed by the United States military from the southeast to Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, we picked ourselves up and rebuilt our nations. We started some of the first schools west of the Mississippi, Indian or non-Indian, and built schools for the higher education of women. We printed our own newspapers in Cherokee and English and were at that time more literate than our neighbors in Texas and Arkansas and actually I think we probably still are. Then in the early 20th century, the federal government tried to abolish the Cherokee Nation and within two decades -- when we didn’t have a functioning central tribal government -- we went from being one of the most literate groups of people to having one of the lowest educational attainment levels of any group in eastern Oklahoma. And so that’s a direct testament to what happens when we have control and when we don’t have control.

For the past 35 years, we’ve been in an effort to revitalize the Cherokee Nation and now we once again run our own school and have an extensive array of successful education programs. The youth at our Indian school, the Sequoyah High School, recently won the state, the team, a student won the state trigonometry contest and several are Gates Millennium Scholars. Again, we do better when we have control over our own destiny. And a couple of years ago Harvard University completed over a decade of comprehensive research, which was published in a guardedly hopeful book entitled The State of Native Nations. The research indicates that most of the social and economic indicators are moving in a positive direction. Many tribal governments are strong, educational attainment levels are improving, and there is a cultural renaissance occurring in many tribal communities.

Within some Indigenous communities, there are conversations about what it means to be a traditional Indigenous person now and what it will mean in the future. I am an Indigenous woman of the 21st century, and I’m so glad I was born Cherokee and that my life has indeed played itself out within a set of reciprocal relationships in my family and community.

To me, being an Indigenous person in the 21st century means being part of a group of people with the most valuable and ancient knowledge on the planet, a people who still have a direct relationship with and sense of responsibility to the land and to other people.

To me, being an Indigenous person of the 21st century means being part of a community that faces a daunting set of challenges and problems and oppression and yet the communities, our communities find so many moments of grace and comfort and joy in traditional stories, in the language and in ceremonies.

I think, to me, being an Indigenous person of the 21st century, all these young smart people getting an education here at the University of Arizona, being an Indigenous person of the 21st century means trusting our own thinking again and not only articulating our own vision of the future clearly, but having within our communities and our people the skill set and the leadership ability to make those visions a reality.

Being an Indigenous person in the 21st century means -- despite everything -- still being able to dream of a future in which all people will support the human rights and self-determination of Indigenous people. We still have that dream and we still have that hope. Land can be colonized and resources can be colonized but dreams can never be colonized. I always think about the time of my grandfather and the early part of the 20th century, during that bad time when our central government was in disarray, and these people never gave up the dream of having a strong central tribal government and a strong community and they would ride horses to each other’s houses throughout the Cherokee Nation and collect money in a mason jar to send a delegate to Washington to remind the leaders in Washington of their obligation, their treaty obligations to Cherokee people. So our people never gave up their dream and will never give up their dream.

Being an Indigenous person in the 21st century means sharing traditional knowledge and best practices with Indigenous communities all over the world using the iPhone, the Blackberry, MySpace, YouTube and every other technological tool that becomes available to us.

Being an Indigenous person in the 21st century means becoming a physician or a scientist or even an astronaut who will leave her footprints on the moon and then return home to participate in ceremonies her people have had since the beginning of time. That’s what it means to be an Indigenous person in the 21st century.

And finally, to be an Indigenous person of the 21st century means to forego the feeling of going around with anger in our hearts over past injustices and it means not becoming paralyzed by the inaction we see around us or the totality of problems we face in our communities. We can’t be paralyzed by that and we can’t be angry over past injustice. I think it’s important for us to keep our view just as our ancestors did. We’re here because our ancestors thought about us and cared about us and fought for us. So it’s our job now to keep our vision fixed on the future. That’s what we need to do.

I really love my favorite proverb, which I’ll leave you with is a Mohawk proverb and because they teach their young people not to always be angry and focus on injustice or not be paralyzed by what’s going on around them, the problems they now face. So what they tell their young people is that you need to be thinking about the future and ‘it’s hard to see the future with tears in your eyes.’ I love that proverb. So I’ll leave you with that proverb, ‘ It’s hard to see the future with tears in your eyes.’ And thank you again for being here and open it up for some time for questions and answers. Thank you.