Indigenous Governance Database

language fluency

In Lakota Nation, people are asking: Who does a language belong to?

From NPR's "Code Switch" podcast episode page:Many Lakota people agree: It's imperative to revitalize the Lakota language. But how exactly to do that is a matter of broader debate. Should Lakota be codified and standardized to make learning it easier? Or should the language stay as it always has…

Cherokee National Youth Choir - Video

This video -- produced by the Cherokee Nation Education Department -- is a sample reel of the Cherokee National Youth Choir, an innovative approach to promoting and encouraging the use of the endangered Cherokee language among its youth while also instilling Cherokee cultural pride. The award-…

LeRoy Staples Fairbanks III and Adam Geisler: What I Wish I Knew Before I Took Office (Q&A)

Leroy Staples Fairbanks III and Adam Geisler field questions from the audience about the role of education in nation building. The discussion focuses on the importance of Native people being grounded in their culture and language, and where and how that education can and should take place.

Gwen Phillips: Defining and Cultivating Strong, Healthy Ktunaxa Citizens

Gwen Phillips, Director of Corporate Services and Governance Transition with the Ktunaxa Nation, discusses how Ktunaxa people gained a sense of Ktunaxa identity and belonging traditionally, and the different criteria that Ktunaxa is considering including among its citizenship criteria today.

Honoring Nations: Dusty Delso: Cherokee Language Revitalization Project

Dusty Delso presents an overview of the Cherokee Language Revitalization Project to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: James Ransom and Elvera Sargent: The Akwesasne Freedom School

Elvera Sargent and James Ransom from the Sain Regis Mohawk Tribe present an overview of the Akwesasne Freedom School to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

Honoring Nations: Elvera Sargent: The Akwesasne Freedom School

Elvera Sargent discusses the Akwesasne Freedom School and the role it plays in the cultural identity of each generation that goes through the curriculum.

Constitutional Reform: A Wrap-Up Discussion (Q&A)

NNI "Tribal Constitutions" seminar presenters, panelists and participants Robert Breaker, Julia Coates, Frank Ettawageshik, Miriam Jorgensen, Gwen Phillips, Ian Record, Melissa L. Tatum and Joan Timeche field questions from the audience about separations of powers, citizenship, blood quantum and…

Hopes of preserving Cherokee language rest with children

Kevin Tafoya grew up hearing Cherokee all around him – his mother, a grandmother and grandfather, aunts and an uncle all spoke the language that now is teetering on the edge of extinction. Yet his mother purposely didn’t teach him. “She told us she had a hard time in school transitioning from…

Chickasaw Nation: The Fight to Save a Dying Native American Language

A 50,000-year-old indigenous Native American tribe that has weathered the conquistadors, numerous wars with the Europeans, the American Revolution and the Civil War is now fighting to preserve its language and culture by embracing modern technology. There are 6,000 languages spoken in the world…

Sleeping Language Waking Up Thanks to Wampanoag Reclamation Project

It’s been more than 300 years since Wampanoag was the primary spoken language in Cape Cod. But, if Wampanoag tribal members keep their current pace, that may not be true for much longer. Tribal members have been signing up for classes with the Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project while families…

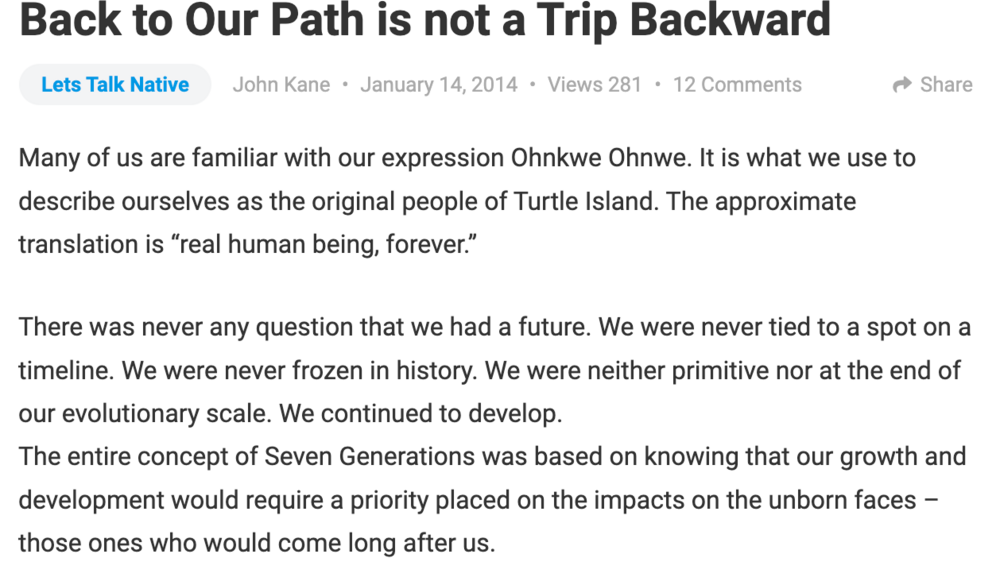

Back to Our Path is not a Trip Backward

Many of us are familiar with our expression Ohnkwe Ohnwe. It is what we use to describe ourselves as the original people of Turtle Island. The approximate translation is “real human being, forever.” There was never any question that we had a future. We were never tied to a spot on a timeline. We…

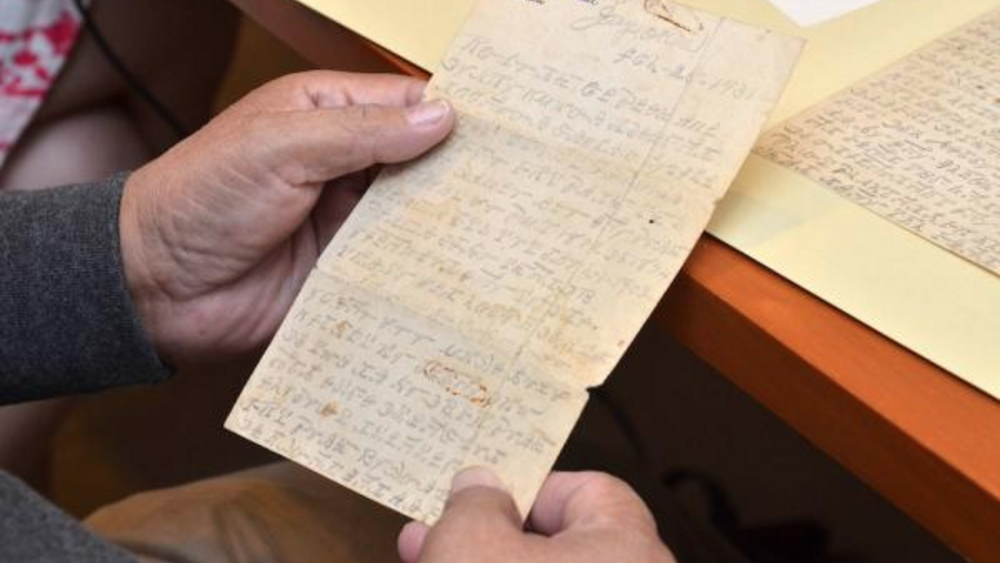

Keeping Language Alive: Cherokee Letters Being Translated for Yale

Century-old journals, political messages and medicinal formulas handwritten in Cherokee and archived at Yale University are being translated for the first time. The Cherokee Nation is among a small few, if not the only tribe, that has a language translation department who contracts with Apple,…

Comanche Nation College Tries to Rescue a Lost Tribal Language

A two-year tribal college in Lawton, Okla., is using technology to reinvigorate the Comanche language before it dies out. Two faculty members from Comanche Nation College and Texas Tech University worked with tribal elders to create a digital archive of what's left of the language. Only about 25…

Addressing the crisis in the Lakota language

With only 2 to 5 percent of children currently speaking Lakota, Thomas Short Bull, president of the Oglala Lakota College, said the time has come to raise the alarm. As the day begins at the Lakota Language Immersion School, a young boy passes an abalone bowl of sage to each child sitting on the…

Huge Push to Save Endangered Seneca Language

The Seneca Nation of Indians have a deep rooted history in Western New York. Stories of their ancestors are here and their culture from ceremonies to traditions is still very much alive. But the language, a huge part of their culture, is dying. That's why there is a big push to preserve the…

The Ways: Living Language: Menominee Language Revitalization

Before European contact, the Menominee Indian Tribe had a land base of over 10 million acres (in what is now known as Wisconsin and parts of Michigan) and over 2,000 people spoke their language. Today, their land has been reduced to 235,000 acres, due to a series of treaties that eroded the tribe’s…

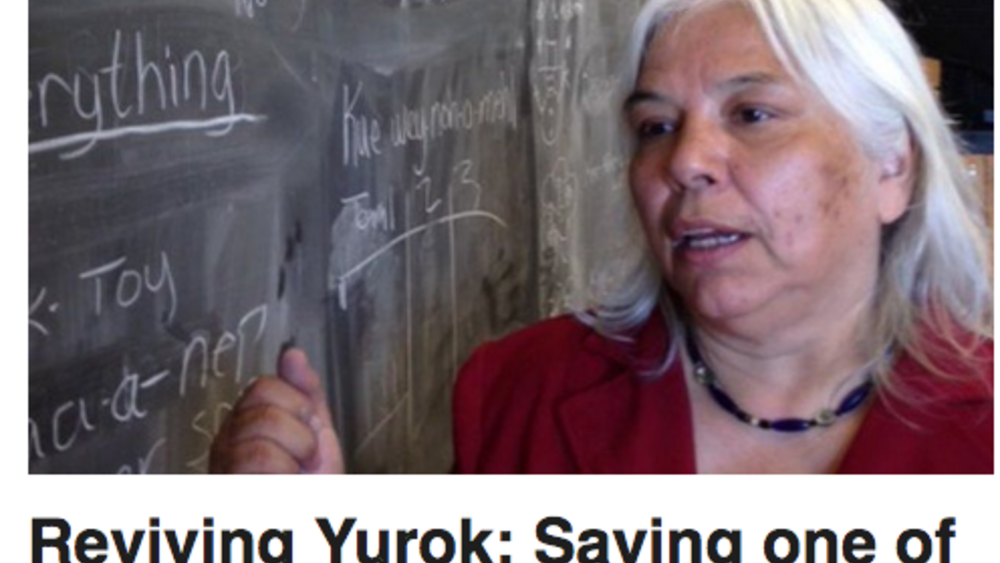

Reviving Yurok: Saving one of California's 90 languages

California is home to the greatest diversity of Native American tribes in the US, and even today, 90 identifiable languages are still spoken there. Many are dying out as the last fluent speakers pass away and English dominates. But one tribe is having success reviving the Yurok language, which was…