Indigenous Governance Database

restorative justice

Leech Lake Joint Tribal-State Jurisdiction

Across Indian Country tribes are strengthening and better defining their governments in order to meet the unique needs of their communities. As Native nations work to expand their sovereign powers, tribal justice departments can play a critical role in achieving those goals. In the early 2000s, the…

Tulalip Alternative Sentencing Program

Born out of a need to create a judicial system that Tulalip citizens can trust and that also helps offenders to recover rather than just "throwing them away," the Tulalip Tribal Court Alternative Sentencing Program supports efforts to establish a crime free community. Focusing on the mental,…

Grand Traverse Band Tribal Court

Constitutionally separated from the political influences of government, the Tribal Court hears more than 500 cases per year, and utilizes "peacemaking" to mediate in cases in which dispute resolution is preferred to an adversarial approach. The Court adjudicates on such issues as child abuse,…

Kake Circle Peacemaking

Restoring its traditional method of dispute resolution, the Organized Village of Kake adopted Circle Peacemaking as its tribal court in 1999. Circle Peacemaking brings together victims, wrongdoers, families, religious leaders, and social service providers in a forum that restores relationships and…

Navajo Nation Judicial Branch: New Law and Old Law Together

The Judicial Branch of the Navajo Nation seeks to revive and strengthen traditional common law while ensuring the efficacy of the Nation’s western-based court model adopted by the Nation. With over 250 Peacemakers among its seven court districts, the Judicial Branch utilizes traditional methods of…

NNI Indigenous Leadership Fellow: John Petoskey (Part 1)

In the first of two interviews conducted in conjunction with his tenure as NNI Indigenous Leadership Fellow, John Petoskey, citizen and long-time General Counsel of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (GTB), discusses how GTB has worked and continues to work to build and maintain…

Joseph Flies-Away: The Role of Justice Systems in Nation Building

In this in-depth interview with NNI's Ian Record, Joseph Flies-Away, citizen and former chief judge of the Hualapai Tribe, discusses the central roe that justice systems can and should play in Native nation rebuilding efforts, how justice systems serve as platforms for healing and cultural renewal…

Kake Circle Peacemaking - Overview Video

This video -- produced by the Organized Village of Kake -- depicts the restoration of traditional methods of dispute resolution the Organized Village of Kake adopted Circle Peacemaking as its tribal court in 1999. Circle Peacemaking brings together victims, wrongdoers, families, religious leaders,…

David Wilkins: Putting the Noose on Tribal Citizenship: Modern Banishment and Disenrollment

The final speaker for the 2008 Vine Deloria, Jr. Distinguished Indigenous Scholars Series at the University of Arizona, scholar David Wilkins (Lumbee) shares his research into the recent and growing phenomenon of disenrollment that is occurring across Indian Country, and delves into the likely…

John McCoy: The Tulalip Tribes: Building and Exercising the Rule of Law for Economic Growth

Former Manager of Quil Ceda Village John McCoy discusses how the Tulalip Tribes have systematically strengthened their governance capacity and rule of law in order to foster economic diversification and growth. He also stresses the importance of Native nations building relationships with other…

Honoring Nations: Robert Yazzie: The Navajo Nation Judicial Branch

Chief Justice Emeritus Robert Yazzie of the Navajo Nation Supreme Court talks about the Navajo Nation Judicial Branch's application of Navajo common law in its jurisprudence as an example of the importance of Indigenous cultural values and common law into the governance systems of Native nations.

Honoring Nations: Rae Nell Vaughn, Dan Mittan, Henderson Williams, Andrew Jones, and Hilda Faye Nickey: The Choctaw Tribal Court System

Representatives from the Choctaw Tribal Court System present an overview of the court system's development to the Honoring Nations Board of Governors in conjunction with the 2005 Honoring Nations Awards.

From the Rebuilding Native Nations Course Series: "What Strong, Independent and Legitimate Justice Systems Require"

Native leaders and scholars discuss what Native nations need to do to create strong, independent and culturally legimate justice systems.

Theresa M. Pouley: Reclaiming and Reforming Justice at Tulalip

Tulalip Tribal Court Chief Judge Theresa M. Pouley shares the long-term, positive effects of the Tulalip Alternative Sentencing Program on the Tulalip tribal community.

Honoring Nations: Tony Fish: The Muscogee Creek Nation Reintegration Program

Muscogee Creek Nation Reintegration Program Manager Tony Fish explains how and why his nation developed a prisoner reintegration program that reflects its culture, combats recidivism, and makes for a safer Muscogee Creek community.

Honoring Nations: Hilda Faye Nickey: The Mississippi Choctaw Tribal Court System

Mississippi Choctaw Chief Justice Hilda Faye Nickey discusses the Choctaw tribal court system, and provides an overview of Choctaw's youth court and how it works to educate Choctaw youth about Choctaw ethics and core values in order to set them on the right path.

Native Nation Building TV: "Why the Rule of Law and Tribal Justice Systems Matter"

Guests Robert A. Williams, Jr. and Robert Yazzie discuss the importance of having sound rules of law and justice systems, and examine their implications for effective governance and sustainable economic development. They explore these issues and their role in creating a productive environment that…

Honoring Nations: Theresa M. Pouley: The Tulalip Alternative Sentencing Program

Judge Theresa M. Pouley of the Tulalip Tribal Court discusses how the Tulalip Tribes reclaimed criminal jurisdiction from the State of Washington and then developed the award-winning Tulalip Alternative Sentencing Program, which she explains is a more effective and culturally appropriate approach…

First-time offenders learn accountability through diversion program run by tribal elders

The 2012 Annual Tulalip Tribal Court Report states 415 criminal cases were heard in court. Included in that 415, are 24 newly filed criminal alcohol charges and 69 disposed, meaning judicial proceeding have ended or a case that has been resolved. Also counted in that 415, are 76 newly filed…

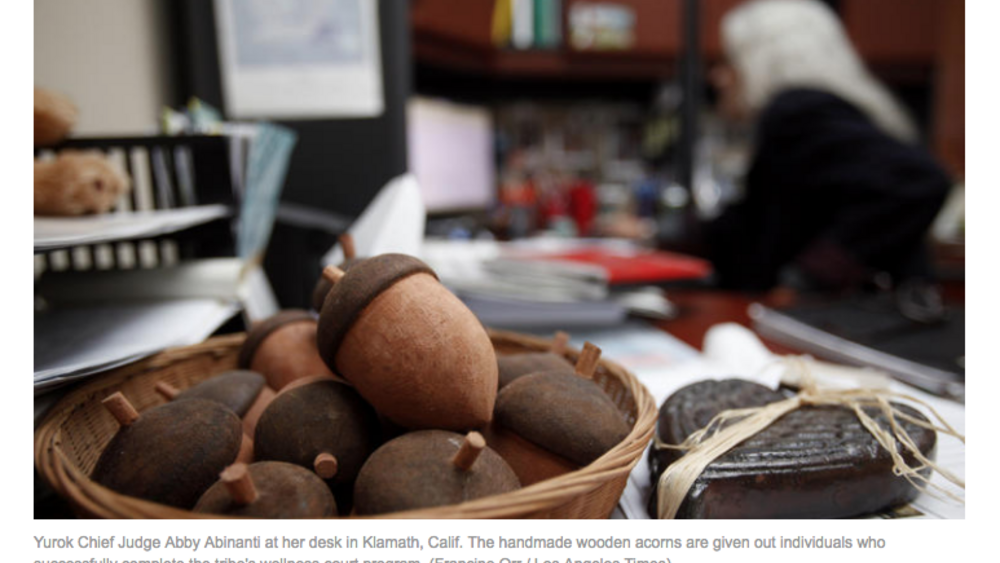

Yurok tribe's wellness court heals with tradition

Lauren Alvarado states it simply: “Meth is everywhere in Indian country.” Like many here, she first tried methamphetamine at age 12. Legal trouble came at 13 with an arrest for public intoxication. In the years that followed, she relied on charm and manipulation to get by, letting her grandmother…