Indigenous Governance Database

constitutional amendments

Wilson Justin: Leadership with Cultural Knowledge and Perseverance

Wilson Justin is a cultural ambassador for Cheesh’na Tribal council and serves as a Vice Chair Board of Directors for Mt. Sanford Tribal Consortium. He relays his expertise and perspective on the intricacies of Indigenous governance in Alaska through adapting cultural traditions, creating a…

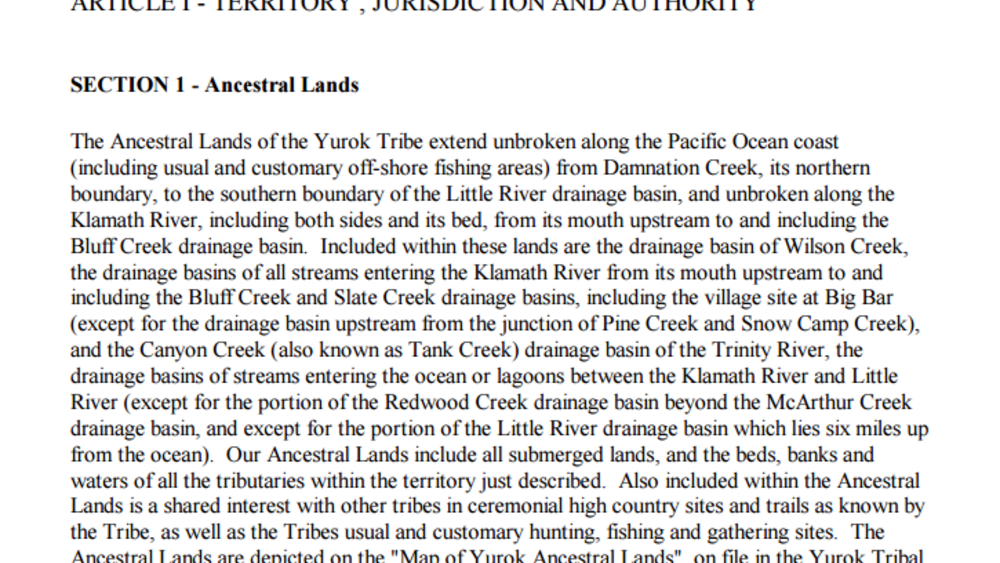

Yurok Tribe: Jurisdiction/Territory Excerpt

ARTICLE I - TERRITORY , JURISDICTION AND AUTHORITY SECTION 1 - Ancestral Lands The Ancestral Lands of the Yurok Tribe extend unbroken along the Pacific Ocean coast (including usual and customary offÂshore fishing areas) from Damnation Creek, its northern boundary, to the southern…

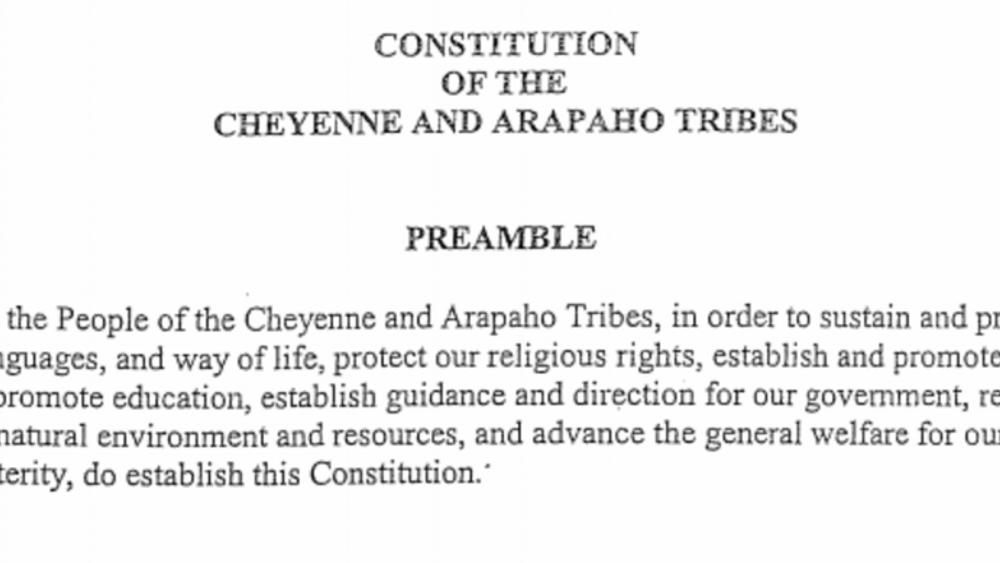

Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes: Legislative Functions Excerpt

ARTICLE VI - LEGISLATIVE BRANCH Section 1. Composition. The Legislative Branch shall be comprised of one Legislature. The Legislature shall consist of four Cheyenne Districts and four Arapaho Districts. Each Cheyenne District shall have one Cheyenne Legislator and each Arapaho District shall have…

Cherokee Nation: Amendments Excerpt

Article XV. Initiative, Referendum and Amendment. Section 9. No convention shall be called by the Council to propose a new Constitution, unless the law providing for such convention shall first be approved by the People on a referendum vote at a regular or special election. Any amendments,…

Crow Tribe: Amendments Excerpt

ARTICLE XII - AMENDMENTS This Constitution may be amended by a two-thirds (2/3) vote ofthe Crow Tribal General Council provided that at least thirty percent (30%) of the Crow Tribal General Council vote in an election called for the purpose of amending the Constitution. The process to propose…

Robert Hershey: Dispelling Stereotypes about the Federal Government's Role in Native Nation Constitutional Reform

Robert Hershey, Professor of Law and American Indian Studies at The University of Arizona, dispels some longstanding stereotypes about what the federal government can and will do should a Native nation decide to amend its constitution to remove the Secretary of Interior approval clause or else make…

Richard Luarkie: The Pueblo of Laguna: A Constitutional History

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Laguna Governor Richard Luarkie provides a detailed overview of what prompted the Pueblo of Laguna to first develop a written constitution in 1908, and what led it to amend the constitution on numerous occasions in the century since. He also…

Jennifer Porter: Cultural Match Through Constitutional Reform at Kootenai

In this informative interview with NNI's Ian Record, Vice-Chairwoman Jennifer Porter of the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho explains what prompted her nation to enact several amendments to its constitution in the mid-1990s, and how its ability to govern effectively has been greatly enhanced by its decision…

Jennifer Porter: The Kootenai Tribe: Strengthening the People's Voice in Government Through Constitutional Change

Jennifer Porter, former chairwoman and current vice-chairwoman of the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, discusses how her nation moved to amend it constitution to change its basis of political representation, how the U.S. Secretary of Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) tried to block the move,…

John Borrows: Revitalizing Indigenous Constitutionalism in the 21st Century

In this thoughtful conversation with NNI's Ian Record, scholar John Borrows (Anishinaabe) discusses Indigenous constitutionalism in its most fundamental sense, and provides some critical food for thought to Native nations who are wrestling with constitutional development and change in the 21st…

John 'Rocky' Barrett: Blood Quantum's Impact on the Citizen Potawatomi Nation

In this short excerpt from his 2009 interview with NNI, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman John "Rocky" Barrett discusses the devastating impacts that blood quantum exacted on the Citizen Potawatomi people before the nation did away with blood quantum as its main criteria for citizenship through…

Vanya Hogen: Redefining Citizenship Criteria Through Constitutional Reform and Other Means

Lawyer and tribal judge Vanya Hogen (Oglala Sioux) discusses the difficulties inherent in amending Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) constitutions to redefine tribal citizenship criteria, and shares the story of the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community as an example of one Native nation with an IRA…

Andrew Martinez: Constitutional Reform: The Secretarial Election Process

Native Nations Institute's Andrew Martinez (Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community) gives participants a concise and informative overview of how the secretarial election process works when Native nations amend their constitutions, and what happens (and doesn't) when Native nations remove…

NNI Indigenous Leadership Fellow: Frank Ettawageshik (Part 2)

Frank Ettawageshik, former chairman of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (LTBBO), discusses the critical role that intergovernmental relationship building plays in the practical exercise of sovereignty and the rebuilding of Native nations. He shares several compelling examples of…

Anthony Hill: Constitutional Reform on the Gila River Indian Community

Gila River Indian Community (GRIC) Chief Judge Anthony Hill, who served as Chair of the Gila River Constitutional Reform Team, discusses the reform process that GRIC followed, the current state of GRIC's reform effort, and what he sees as lessons learned from Gila River's experience.

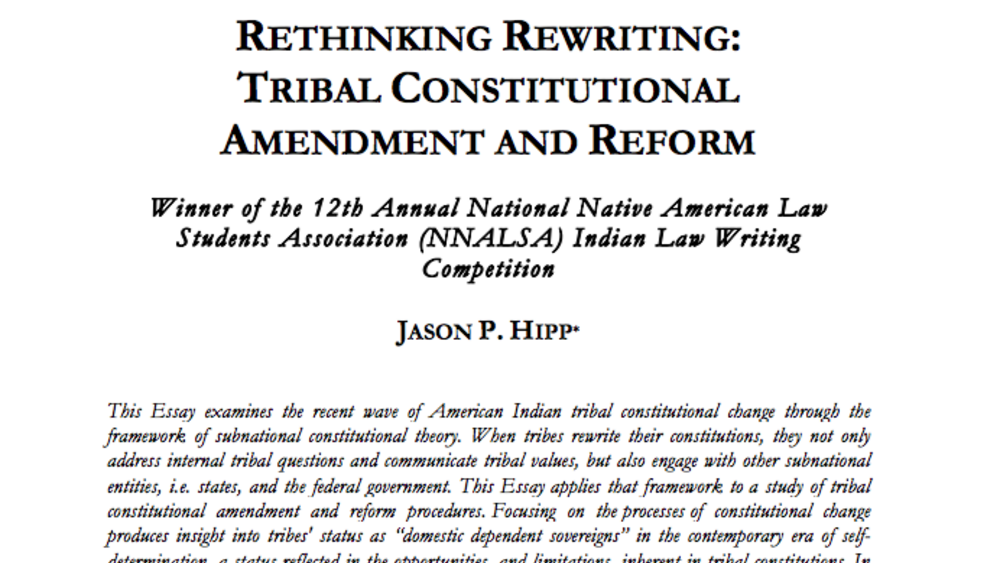

Rethinking Rewriting: Tribal Constitutional Amendment and Reform

This essay examines the recent wave of American Indian tribal constitutional change through the framework of subnational constitutional theory. When tribes rewrite their constitutions, they not only address internal tribal questions and communicate tribal values, but also engage with other…

A Guide to Community Engagement

In this third part of the BCAFN Governance Toolkit: A Guide to Nation Building, we explore the complex and often controversial subject of governance reform in our communities and ways to approach community engagement. The Governance Toolkit is intended as a resource for First Nations leadership. It…